|

TennisOne Lessons Why the Greats Never Won on Clay Philippe Azar

Following his recent defeat to a no-name Italian qualifier in the Rome ATP Masters and his consistent inability to dent the defenses of the clay court messiah, Nadal, it looks increasingly likely Federer will once again walk away empty-handed at this year's French Open. In fact - and despite us not wishing it upon him - it's almost conceivable that he might finish his career without the one title he so desperately yearns for and that would elevate him from tennis-legend to tennis-immortality.

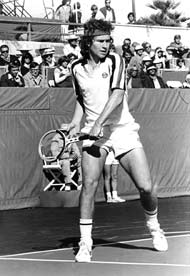

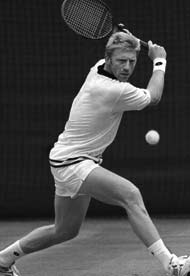

But he might take solace in the fact that he is in eminent company because a rather long list of tennis greats have all failed the same way Federer has so far. Tilden, Newcombe, Ashe, Connors, McEnroe, Becker, Edberg, Sampras - despite their legendary status, despite their numerous conquests and achievements on the tennis world stage – all never managed to win the French Open. Coincidence or inevitable, you ask? Predictable, I tell you.

So let’s go through each one of these elements and examine why clay court specialists always did and probably always will have the upper hand on the legends. Patience Clay courters go into a match with a unique mantra: "I recognize and accept the fact that this court will be my home for quite possibly the next five hours." The top clay courters don't just recognize and accept this; they embrace the prospect of grinding every point out, game after game, set after set, hour after hour. In fact, it almost seems like the longer the rally gets, the more they are inclined to keep it going. Not only that, but clay courters are ready to renew the battle after every point, and hitting the ball 10 or 20 times over the net is not the exception but the rule. The prospect of these endless rallies has been the downfall of Sampras and company who have all too often succumbed to impatience in attempting to force their offensive boom-or-bust antics on clay.

Recovery In the 1991 Wimbledon final between Becker and Stich, the ball was play for an average of 3 minutes and 42 seconds per hour (that is the actual time that the ball was in rally), and the average rally length was of 2.65 seconds. In contrast, the French Open final that same year, featuring Courier versus Agassi (both of whom are not considered as classic clay court specialists but have nevertheless managed to win Roland Garros), had an average of 14 minutes and 56 seconds of play per hour with 10-second average rallies. This demonstrates that the ball is in play for much longer time periods on clay and the rallies are inherently more grueling. But the 20 second recovery time given to players between points remains the same regardless of surface, intensity of rallies and length of match. A great clay courter differentiates himself from the pack with his ability to recover very fast not only after each point but after each match. Thomas Muster, the legendary clay court specialist, was infamous for his prolific conditioning and strength: the longer a match wore on, the shorter the breaks he would take between points. He often did not even bother to sit down at the changeovers, preferring to jog straight over to the opposite baseline and wait for his opponent there: a psychological ploy designed to disturb and discourage his opponents. And there are parallels amongst present day players. Nadal - the modern king of clay - is a physical specimen like no other in tennis history and his compatriot clay courters are all armed with bundles of muscles, all the result of hours of physical preparation on and off court. Intelligence

Otherwise known as ‘tactical awareness’, this is probably the key difference between those who have succeeded and failed in Paris. Clay courters have a solid defensive foundation – the ability to get out of trouble when the opponent has put them in an emergency. Nadal is always aiming to make his opponent play one more shot, while Becker was always aiming for the opposite, namely to prevent his opponent from playing one more shot. And while tactically, going for winners might work on faster surfaces, the nature of clay absorbs the speed of the ball and thereby neutralizes big serves or other power shots. On grass, a ball keeps approximately 70% of its original velocity once it has bounced. On clay however, that drops to 59%. It might not seem like much but it makes a big difference in the available time a player has to retrieve an attempted winner from the opponent. Hence, clay courters have recognized that the two or three shot combinations that might work on faster surfaces, such as a reliance on a booming serve to set up for an easy put-away, cannot consistently or effectively be replicated on the dirt. As such, they know that constructing a point can take many more shots than Connors and company were ever willing to commit to when they competed at the French Open. Clay courters are ready to set up a tent on the baseline and play 20 or 30 shot rallies, patiently waiting for a real opportunity to arise. The surface does not favor risk-taking and these specialists - who often grew up on the surface - have an intrinsic ability to play tennis like a game of chess, anticipating actions and reactions 3 or 4 shots ahead. The top clay courters spend much of their training hours working on the consistency of their groundstrokes. On grass, only 16% of all shots are groundies, while on clay, it suddenly rises to 55% or more depending on the player. A successful clay courter therefore needs not only the ability to hit the ball consistently over the net, but needs to be able to hit consistently deep in order to prevent offensive shots from their opponent. The stroke of choice for this is topspin, as it allows the ball to travel both fast and high over the net, thereby landing deep into the court and kicking off fast.

Clay courters have made a career out of keeping things simple by concentrating primarily on their ability to consistently hit topspin groundstrokes as deep as possible. And while Becker and company were more than able to hit beautiful topspin, their ability to also produce every other kind of shot in the game was their ultimate downfall as they tended to overcomplicate or oversimplify their game plans on clay. Endurance A clay courter's arsenal revolves around topspin groundstrokes, which keeps the ball heavy, deep, and consistent. To generate this spin, it has been calculated that the racquet head needs to travel twice as fast compared to a backspin shot, which roughly equates to twice the amount of aerobic/physical input. Every player walks onto the court with a certain physical bank account. The initial size of this account is decided by the endurance or fitness level of the player. With the passing of every shot and point, a withdrawal is made from that account. The longer the rallies are, the bigger the withdrawals. The longer the match wears on, the smaller the available funds become. Clay court specialists need to be the fittest players on the tour. Which is more than can be said for McEnroe and company whose physical bank account has often become overdrawn much faster than it should.

Contrary to common opinion, which would lead us to believe that Wimbledon is "The" tournament of tournaments, some believe the French Open to be the crown jewel of all tennis events. They argue that to win Wimbledon, which is played on grass, the fastest surface on the tour, players don't need to be particularly fit or particularly smart. More often than not, rallies are as short as one booming serve, followed by a put-away volley and don’t favor the consistent player but the competitor who has the shots to overpower his opponent. Wham-bam-thank-you-ma’am! On clay however, there are few freebies and no shortcuts. One rally might see the ball going forwards and backwards 20, 30, 40 times. Players may well be forced to run forwards, backwards and sideways for up to 5 hours, and have their physical limits tested point after point. The potential for dramatic exchanges, twists and dramas is much higher at the French Open. Who will ever forget the Lendl-Chang match back in 1989 where Chang had to fight through cramps and serve underarm after more than 4 hours of grueling rallies? Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Philippe Azar's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Philippe Azar is a professional with Peter Burwash International (PBI) and has been teaching tennis internationally for more than 15 years. He is presently based at Tokyo Lawn Tennis Club in Japan. PBI contracts with resorts, hotels and clubs all over the world to direct tennis programs.The company presently has professionals working at 62 facilities in North America, Europe, Asia, Middle East, Caribbean, Pacific and Indian Ocean. During its 30 years in business, PBI tennis professionals have taught tennis to over three million students in more than 135 countries. For more information visit: pbitennis.com |