|

TennisOne Lessons Unforced Errors and Error Reduction in Tennis Howard Brody, Physics Department, University of Pennslyvania A typical tennis player will lose many more points through errors than through winners hit by the opponent. Only at the highest level of tennis is the number of winners comparable to the number of unforced errors.

There are a number of ways in which a player's error rate can be reduced. Errors come about because the ball has hit the net, gone long (an error of depth), or gone wide (a lateral error). This article discusses the issue of lateral errors. Shots that are aimed to go straight down the middle give quite a sizeable margin for error - almost ten degrees to the right or to the left before the ball lands in the alley. However, most players do not want to play safe and hit every shot down the middle. They want to be aggressive and go for the corners or down the sideline. They may want to (or have to) pass an opponent at the net. They may want to go for an occasional winner or at least make an opponent run for the ball once in a while. But this invites lateral errors. Changing Ball Direction and the Laws of physics The number of errors from shots that go wide can be reduced even when players go for corners or sidelines if they remember a piece of critical advice: Do not change the ball angle! If a shot is coming cross-court, return it cross-court. If a shot is hit down the line, return it down the line. Changing the ball angle by attempting to return a cross-court shot down the line, or return a down the line shot cross court is asking for problems with lateral errors. The reason lies in the physics of ball-racquet interaction. If a return does not change the ball angle, the ball's impact direction is perpendicular to the face of the racquet at contact. The ball will then leave the racquet in a direction perpendicular to the face of the racquet. It will go out in the direction of the racquet motion, whether the players swings hard, softly or somewhere in between.

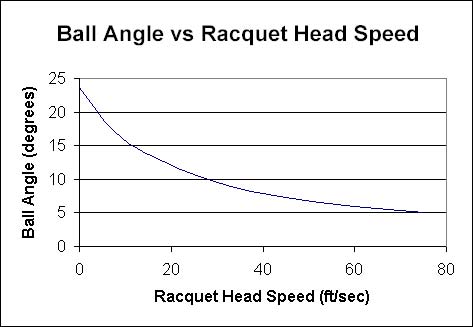

However, this is not the case when a player tries to change the ball angle. The direction that the outgoing ball takes relative to the racquet face then depends on how hard the racquet is swung. The higher the relative ball-racquet speed, the closer the ball will be to perpendicular to the racquet face as it leaves the racquet. This is illustrated below. If the swing is slow, the ball leaves the racquet at a larger angle. The same advice holds for the volley. With a hard return, the ball will go close to where it is aimed. However, if a player just tries to block the ball on a volley and is changing angles, the ball will slide off at a large angle, possibly going wide. Changing Angles If every shot is returned to where it came from, however, an opponent will quickly catch on. So, there are times when changing direction is necessary. But, a player who knows the facts about ball-racquet interaction can reduce the errors that might occur even when changing the ball angle. If the ball is not going to be hit hard, it should be aimed a little closer to the centre of the court. With a hard swing, the shot can be aimed closer to the sideline or the corner with confidence. The famous statement that the angle of reflection equals the angle of incidence holds for light reflecting from a plane mirror, but not for tennis balls rebounding from a racquet.

Often, in a match, a player may ease up if he or she is well ahead of an opponent, and will not hit shots quite so hard. This can reduce the likely errors of depth, but can also lead to a problem. If the ball is still aimed the same way, but the swing is no longer as hard, balls that previously went down the line may now end up in the alley. A similar problem can be the result from changing the game plan in the middle of a match. A player may become concerned about the final outcome, so instead of hitting out and playing his or her regular game, decide to play it safer and ease up on the strokes. Again, balls that previously went down the line may now end up in the alley. The player ends up making more, not fewer errors. People will claim the player 'choked'. But what actually happened is that they did not understand the laws of physics. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Howard Brody's article by emailing us here at TennisONE.

Professor Brody is a member the International Tennis Federation Technical Commission, the USTA Sports Science Committee, USTA Technical Committee, science advisor to the Professional Tennis Registry, technical advisor to the United States Racquet Stringers Association, on the Editorial Board of the Journal of Sports Engineering, and on the technical advisory panel of Tennis Magazine. His book Tennis Science for Tennis Players was published by the University of Pennsylvania Press in 1987. He and Vic Braden are featured in a video “The Science and Myths of Tennis.” As one of the principal authors who have written an NSF sponsored high school physics course (Active Physics), he was responsible for the chapters dealing with the physics of sports. He has received the USPTR Plagenhoef award for sports science in 1996 and the International Tennis Hall of Fame Educational Merit Award for the year 2000. His latest book, The Physics and Technology of Tennis, written with Rod Cross and Crawford Lindsey was published in late 2002. He is also one of the principal authors of the CD-ROM on The Science of Tennis funded by the Lawn Tennis Association Coach Education. At the 2003 Tennis Science and Technology Congress, the ITF gave a prize for the best paper presented and named it the “Howard Brody Award” for his service to tennis. |

Dr. Howard Brody is an emeritus professor of physics at the University of Pennsylvania , where he was interim varsity tennis coach for part of the 1991 season. He played varsity tennis and earned his bachelor's degree at MIT and his master's and doctoral degrees at Cal Tech. Recently he has been investigating the physics of sports, particularly tennis. He has written many papers and articles on the subject, given numerous lectures and talks on tennis, and done several television programs explaining the science behind tennis, football, and baseball.

Dr. Howard Brody is an emeritus professor of physics at the University of Pennsylvania , where he was interim varsity tennis coach for part of the 1991 season. He played varsity tennis and earned his bachelor's degree at MIT and his master's and doctoral degrees at Cal Tech. Recently he has been investigating the physics of sports, particularly tennis. He has written many papers and articles on the subject, given numerous lectures and talks on tennis, and done several television programs explaining the science behind tennis, football, and baseball.