|

TennisOne Lessons Teaching the Forehand Ray Brown

When I began to learn tennis in the 70's, the emphasis was on technique and templates (teaching each stroke as a single unit). We have discussed the idea of templates and the follow through and why they were conceived in our last article, The Follow Through. In this article, I will focus on the methods we use to teach the forehand. But before we begin, a word about how we organize tennis education is in order. Backdrop of our Program In the figure on the right, we see our skills pyramid in which everything rests on clean contact. We also see that speed must ultimately rest on control and consistency. And stability makes no sense unless there is clean contact first. In our program, we develop all elements in a holistic approach. The most obvious reason is that at the level we train students, you don't really have a forehand unless you can hit the forehand consistently and accurately on the run and at high speeds. Thus choreography, i.e. footwork, precision movement, anaerobic endurance and technique must all be developed in a single combined curriculum to advance the student at the fastest pace. All of these terms are self explanatory except 'precision movement' which is illustrated in the video below. What we see is Dinara Safina hitting an effective shot from a very awkward position. Precision movement training is needed to develop the skill to hit effectives shot from such positions. It is interesting that by developing the ability to hit the really difficult shots well, one develops the ability to hit standard shots with ease. The Generic Components of the Forehand

We recognize five components of the forehand: (1) the take back, (2) contract, (3) rotate, (4) accelerate, and (5) strike/contact. In this article we will focus on the contact component. We do not specifically focus on the other components by name, but rather use exercises that implicitly develop the component. If a component is not developing properly, we will have to address that in isolation, but only as a last resort. Generally, if we get the contact right, our exercises lead to the development of the other components naturally. The Forehand Contact In contrast to classical methods, we do not teach templates or the follow through. The reason for this is that the research of Freeman and Langer have established that the brain does not process this information efficiently. Hence, in order to develop a new, more efficient method, we designed our program around two principles of learning. One is that the brain learns more efficiently by organizing information by relevance and purpose; and two, the brain is organized around the use of components, not templates.

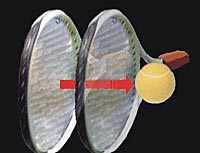

This approach raises the question "what are the relevant components that make up the forehand?" Components fall into three broad categories: contact, speed, and stability. All strokes can be organized around these categories that are "results oriented." Note that every stroke is organized around these same classes. Contact has two components: The straight-line interval and the Ballistic Reflex. As the Ballistic Reflex is a very advanced component we only explain the straight line component which is where we begin the study of the forehand for every student. In the figure below the straight-line component is illustrated: What we see in this figure is the racquet moving in a straight-line through the path of the ball for as much as 18 inches.

The USPTA uses a metaphor that goes something like this: "The student should think of extending the racquet forward as if they were hitting 8 or so balls instead of just one ball." The straight-line motion maximizes the potential for clean contact between the racquet and ball, particularly at high ball speeds. Teaching this component can be difficult since there are various elements that can be used to produce straight-line motion, and there are natural reflexes that interfere with learning a straight line component. Before we go on, we must address a common question that pros ask us: "Won't the student stop their swing after hitting the ball if you only mention the contact?" The answer is "not generally." If this does occur, then it can be addressed on the spot and quickly resolved. We rarely see this particular problem in our Academy. Below we have an example of Roger Federer using the straight line motion.

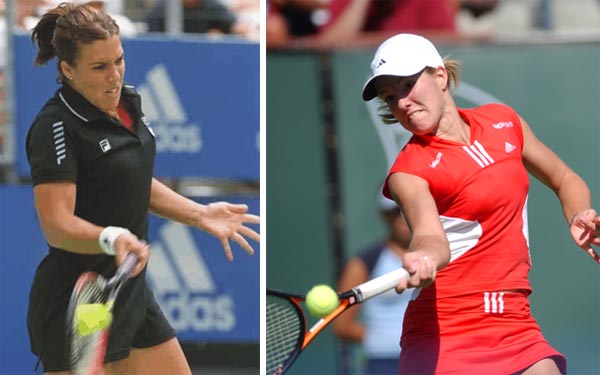

Note that the racquet is still moving in a straight line even after Federer makes contact with the ball. Once these ideas are in place, we can begin the short court rally using only the ballistic reflex and the straight line motion. The straight line interval component will require many iterations before it will begin to take shape so we will need to begin other elements of the forehand simultaneously. In particular, we must begin choreography at once. Two Theories of the Forehand The vast majority of forehands are a combination of two forehand types. The distinguishing feature is the placement of the elbow at contact. We teach both elbow components and let the student settle on their personal style. Type I, the simplest, is illustrated by the punch forehand. In this forehand, the elbow is close to the body but not in front of the body. This is similar in dynamics to a boxer of karate movement. The second type, we call type II, is quite different in that the elbow is in front of the body. In the type II forehand, the elbow is well in front of the body while the racquet butt is still pointing toward the opponent's side of the net. Most players are a combination of these two types. There are advantages and disadvantages of each, but we teach both elbow components and let students gravitate to their own style.

The Grip The grip is a very personal matter. However, power grips (western, semi-western and far western) dominate today's game. We teach them all as well as explaining the history of grips starting with the continental grip. We demonstrate that is is possible to do a short court rally and move through all grips without missing a shot. Since we only prepare players for the power game of today, we recommend a power grip at the outset of the student's education. Forehand Choreography

Forehand choreography refers to the footwork needed to hit the forehand. There are two components to this area of instruction. Agile feet must be able to make four inch adjustments in order to hit the perfect shot and a separate type of footwork is needed to approach and setup at the point of the strike. Agile feet are developed generically using cone drills. Approach and set up are developed with cones and specialized drills. Among the many cone drills we do to develop agile feet is the three cone drill illustrated here. The idea is to move efficiently between the cones in a specific pattern using small steps. This educates the feet to be able to make adjustments to the ball as small as four inches, the difference between a miss-hit and a perfect hit. Without this, students will struggle to develop a forehand quickly because each ball that is fed is a little different, and if students are not capable of making small adjustments, they will have to resort to improvisations to hit the ball. These improvisations can be mistaken by the instructor for a lack of ability to execute technique correctly and so the instructor is in danger of miss diagnosing the error. By developing agile feet from the start, we are less likely to mistaken a footwork error for a forehand execution error. In addition to agile feet, we must begin development of approach and setup skills early. We use both cone drills and ball drills to develop this area of footwork. They are introduced at the earliest possible stage of development. Approach and setup drills require development of body control skills which requires weight training and special core and leg development exercises. All of this is necessary to start at the begriming of a student's training if we are to develop the forehand quickly and efficiently.

Forehand Stability The foregoing leads to a discussion of stability. If the student is not stable, then he will not be able to execute a proper forehand. This requires us to address core strength at the beginning of the students study of the forehand. While we have many exercises for the core, the ab roller is one of the most revealing in that it gives an insight into the core strength in a simple and straightforward way. The ab roller exercise is illustrated in the figure above right.

A simple leg strength exercise for students over the age of 14 is illustrated above left. In the photo, the student is doing lunges wearing a 40 pound vest. By developing the core and leg strength, we better assure that the errors in technique we see in the student are truly errors of technique, not errors brought on by a lack of strength or footwork skills. The Body is Used to Generate the Power A common misconception is that one executes a stroke with the arm whereas in fact, it is the legs, core/hips and shoulder rotation that provides the engine to "swing" the racquet and the arm is mostly the instrument that holds the racquet, coming into play at the end of the stroke. Thus, we must require special exercises to develop the skill to 'swing' the racquet using the body with the arm being led by the body, and the arm using body as a lever. While this is well known, failure to develop the ability to use the body as the source of power, early on, through specialized exercises will result in a great loss of time. A specialized rotation exercise we use is illustrated above. This exercise develops the core rotational power. The weight in the video is 25 pounds. We use many other core development exercises that have been described in other articles. Acceleration

We have mentioned the contact and stability components above. We now turn to the acceleration component. In the video we demonstrate an important exercise to develop acceleration. It is called the static ball exercise. The objective is to hit the ball at the highest possible speed. At first, the balls will go wild. However after s few sessions control will develop, especially if you have done the stability exercises, and the balls will have both speed and accuracy. Key to acceleration are the legs. They must be powerful enough to produce this kind of speed from a tossed ball. The player in the video can leg press 600 pounds, three sets of twelve. By stepping through the video one frame at a time, the method she uses to produce acceleration can be studied in detail. In addition to the legs and core, one should pay close attention to the elbow dynamics and how the racquet is dragged forward, like a rope. with the butt pointing outward toward the ball. Note that the player is using the type II forehand. Forehand Study To illustrate many of the ideas above, we use a TennisONE slow motion video of Martina Hingis. In the video, four points of interest are labeled.

Each component is addressed in our program. The toe (1) must drive the body forward at contact. This is different from the classical weight shift from the back foot to the front. The drive requires powerful legs, and, to avoid bending at the core, the core must be very strong. The head will need strong neck muscles to avoid being unstable at contact, and the feet must we wide spread to absorb the forces that are equal and opposite to the rotation force. While the right leg is supplying power, the left leg supplies balance. Note that Hingis is using the type II forehand. Summary As must be clear from our program, technique, footwork, stability, anaerobic conditioning, and upper body, core and leg strength are all so interconnected that there is no possibility of separating them. To teach technique in isolation from these other elements is a risky business and will require many more years of training than teaching them as a unit. In short, serial processing is much slower than parallel processing. More seriously, by confusing a problem of footwork or leg strength with a technique error can lead to a breakdown in student confidence and self image. Every good educator knows that without confidence, learning will be slow going, or will come to a stand still. Further, to advance the student at the fastest possible pace, one must present the information in a form that is compatible with how the human brain works. The great masters were unable to do this due to a lack of scientific data in their day. This data has only become available recently (late 1990's) through the work of Freeman and the work of Langer. Third, and this cannot be illustrated, one must have a teaching program that is tailored to each student as an individual and one that is attuned to their strengths. The component-based approach is exceptionally well-suited to address this issue. Fourth, it is also valuable to understand the role of sleep, diet, and the energy systems and how they affect the learning process. Fifth, the dramatic physiological and anatomical differences in the human body, and the differences in personalities, confirm that, today, there is no such thing as "the" forehand; every student's forehand must be developed with this in mind; component-based training allows for these differences. Last, one must understand and apply sound principles of teaching if the student is to have an environment in which they become empowered to learn. Of particular importance is to avoid micro management of the student and allow for the natural exploration process to go forward to assist the learning process. Rapid development of skills is still an art, but today this art rests heavily on science at a level it has not in the past. As demonstrated by our program, without a strong dose of science, the development of tennis skills will be inefficient and unrewarding to both student and instructor. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Ray Brown's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Over the past fifteen years Ray has been working in the area of neuroscience, medical research and brain dynamics while coaching tennis. During this time, he has developed new methods of training that greatly accelerate player development. Ray now operates The EASI Academy in McLean Virginia click here. Ray now operates The EASI Academy ( a unique tennis training center for top high school, college, and professional players) that integrates stroke production, footwork, precision movement, anaerobic conditioning, and mental toughness training in a single program where the student to instructor ratio is 1:1. Ray received his Ph.D. in mathematics from the University of California, Berkeley in the area of nonlinear dynamics and has over 30 years of experience in the analysis of nonlinear systems. He has published over 50 articles on tennis coaching and player development and over 35 scientific papers on complexity, chaos, and nonlinear processes. |

Ray Brown, Ph.D.

Ray Brown, Ph.D.