|

TennisOne Lessons Why Isn't Knowing the Perfect Stroke Sufficient to Execute it? By Ray and Becky Brown A common question we hear is "Why can't I learn a stroke in a week if I have perfect information on how to do it?" There are several reasons for this and there are four that we call the Big Four: (1) Dropouts, (2) Imagined Knowledge, (3) Components, and (4) Emotions (DICE). DICE is a good acronym because unless you understand the role of these four problems in learning, you are in effect just rolling the dice on each stroke.

In this article we are going to explain the four DICE problems, give examples of where they apply, and then address how we can better approach them to accelerate the process of learning to hit great shots. Our discussion will consider both the student and the instructor. Dropouts Imagine you are trying to execute a stroke. As you proceed, you try to recall some aspect of the stroke you are determined to get right. When you do this, your focus shifts from the stroke to the retrieval of a memory and back again. However, during the time you were "away," some other element of the stroke should have been executed, but due to your shift in focus it 'dropped out'. So while you may have gotten the element you wanted into your stroke, some other essential element was lost in the process, causing the stoke to breakdown in spite of your efforts. When this occurs, frustration often follows. Worse still, the student can engage in very negative social interpretations of their perceived failure to get the entire stroke right. But this is a mistaken reaction. You could not possibly have got the entire stroke right due to the dropout phenomena, so frustration is misplaced. At this time, there is no known remedy for the elimination of the dropout phenomena which, in fact, is a natural aspect of how our brains are put together. We will explain a work around later in the article. Imagined Knowledge We know what imagination is, but what is "imagined knowledge" and how does it fit into learning a tennis stroke? The answer is this: We all understand there is a difference between what you know and what you think you know. If these two ideas are not accurately aligned in your mind, then you have experienced "imagined knowledge."

The problem with imagined knowledge is that it can lead to a learning roadblock. A common occurrence that can indicate misalignment between what you know and what you think you know is that your development progress stalls. Some very important research on the alignment of thought is due to Professor Walter Freeman at UC Berkeley and is summarized in his book Societies of Brains. Freeman's observations are a little involved for a tennis article, but the short story is this: When we experience a sensation such as a ball approaching, a process begins in our minds in response to this stimulus. However, instead of this process remaining carefully guided by our factual knowledge, this response can take on a life of its own and wander far a field from the facts of our situation. When this happens, we begin to respond to what we think is our situation rather than what our situation actually is. As a result, you can hit a really bad shot just when you were sure you were going to hit a great shot. Such experiences, which we have all had, come from a misalignment between what we think we know about our environment and what we actually know. A common metaphorical approach to this problem is for your coach to say "stay focused. Sometimes this is helpful, but not consistently. A very different example occurs when our instructor tells us during drills that our elbow is behind our body plane but we are dead certain that it is out front of the body plane where it belongs. I have seen students swear over and over that they have their elbows in front of their body plane when in fact they do not. The misalignment between what we sense and what is fact is even greater for our bodies than for data that arises from the external environment. In the absence of accurate sensory feedback (which generally does not exist in a normal person) that tells us where our elbow is, we generate false knowledge about where it is and act on it. Now, when you execute your forehand while your elbow is not in front of the body plane, the shot will likely go badly.

All of this is quite normal, but it has serious consequences for the learning process. If the student persists in their view, they may reach a roadblock that stifles their learning process. In the worst case, the student never advances their skills and never knows why. On the other side of the coin, instructors are often convinced they can see features of a student's stroke that are not actually present. Because the most important part of a stroke takes place faster than the human eye can discern, instructors as naturally inclined to fill in the parts of the stroke they did not see with very inaccurate descriptions. For example, it is easy to think a student is using their wrist to produce racquet speed when they are using upper arm rotation. If an instructor makes this mistake, a student will become frustrated in his/her attempts to satisfy the instructor's demands. As a result, the student's learning process may become stifled, or worst for the instructor, the student may take their business elsewhere. The fact is, it is just as easy for the instructor to imagine a stroke was wrong when it was right as it is possible for the student to be convinced they have it right when it is wrong. Sorting out fact from fiction is very difficult and by far the hardest problem the student or instructor will face. However, there is help. The video camera is possibly the simplest solution to this problem. But it may be the most costly for some students and instructors who cannot afford $400 or more for a camera and $5.00 or more for tapes.

In this case, one can improve their development by just realizing that what they think they are doing may be very different from what they are actually doing and this can be the reason progress has stalled. Once this is clear, you may be more receptive to the possibilities that seemed, at first, far fetched from your perspective. Once you are open to possibilities, you and your instructor can begin a systematic approach to solving the problem by testing your ideas together. Components Our bodies and brains are built up from components. With regard to the body, this is well understood in the tennis community. For example, there are abundant programs designed to build up individual muscle components to improve a specific skill. However, our brains are also built up from components. There are microscopic components such as neurons and there are (relatively speaking) large components such as the amygdala. What has only recently been understood is that there are intermediate structures that are not defined by a physiological boundary and these are referred to as mesoscopic components (see Freeman, Neurodynamics: An exploration in mesoscopic brain dynamics). The key characteristic of a component of a stroke is that it provides some essential function to the stroke. For example, racquet acceleration is a function that is useful in a tennis stroke. Another example is stability. Any component of action that can provide either of these two functions would be a mesoscopic component. In general, mesoscopic components are the elements that are essential to learning anything. Just as it is necessary to have certain physical components to hit a good forehand, you must also have certain neurodynamical components as well. The neurodynamical components control the use of the physical components that are in turn used to execute a stroke. Even if someone gave you perfect information on how to hit a stroke (which no one can do), if you are missing any component, physical or neurodynamical, you will probably not be able to do it. In light of this, it would seem a bit far fetched to get upset about not being able to hit a great forehand if you have not developed all necessary components to do so. Further, to the extent that you are unable to do so today, you are likely missing some essential component of the stroke either physical or neurodynamical. Understanding the role of components in learning in general sheds light on many common experiences we have had in learning tennis. For example, why do some teachers have greater success than others? It may be their understanding of the components involved in a stroke (and their ability to communicate what they know). Generally, for each instructor there is a set of components they understand and usually this set is not complete. This explains why changing instructors can often lead to renewed progress when your development seems to have stalled. It is not the only reason however. Components and drop outs are related. So one way to address both at the same time is to organize part of your practice around components. Once a component has been developed to some degree (it doesn't have to be perfect), it is possible to consciously insert it into a stroke without a drop out. The reason for this is that insertion of a developed component into a stroke sequence is far faster than trying to insert a component while you are also trying to develop it. Further, if you insert components in a systematic way, you will be able to assemble them into a complete stroke faster than just leaving it to chance. Luckily, this is consistent with how our brains work most efficiently: first develop useful components and then assemble them into useful actions. It is possible to develop the components while assembling them (which is closer to the traditional model), however, this can takes years longer for the average person than isolating on components first. Players who we call talented often have some key components (both physical and neurodynamical) in place at an early age. This is nothing more than statistical variation in the population. Once a component is understood, almost anyone can learn it in a short period of time. We find that a student can obtain a basic level of component development in about six weeks. While the number of components needed to execute all strokes is several dozen, six common examples are:

All of these components are used in professional technique, but just knowing how they are done and what they do does not necessarily mean you can do them. You must focus on their development and control as clearly as you would focus on learning how to write the letter "A". There are two parts to the learning formula, the physical and the neurodynamical. For example, if you don't presently pronate, then you probably don't have the muscular components necessary to do it routinely. You have to build them up with exercises. Once the muscular components are in place, you still have to control them to direct the acceleration into striking the ball. This might involve throwing up a ball and trying to strike it until you are able to strike it consistently or some other exercise to develop control. The entire process may span several weeks even though the information about pronation can be conveyed in writing and illustrations, and understood in only a few minutes. A problem in learning components is that the student may imagine they should be able to execute them once they are understood. This is a good case of imagined knowledge. Humans in general imagine that they know how the human body and brain works simply because they have one. Most people equate understanding how a skill is performed with possessing the skill. Clearly this is a mistaken view, widely held and vigorously believed and defended in the face of overwhelming evidence to the contrary. Everyone has to cope with this misalignment between the facts and beliefs, and the better we do this the faster we can learn new tennis skills. We emphasize that this is a completely natural starting point for human thought. There is nothing abnormal about it. It is just one of the obstacles we face when learning. Generally it is the unstated purpose of exercises to develop specific physical and neurodynamical components. The key to rapid development is selecting the high leverage components and constructing the right exercises to develop those components. Emotion Emotion is essential to human survival. It is has always been with us in some form throughout our evolution. Since we cannot escape it, it is essential we understand the role of emotion in learning if we are to develop our stokes at the fastest pace possible. Emotion colors information, usually in a manner that results in introducing some inaccuracy. Understanding that your emotions can distort the learning process is the first step in getting control of this aspect of stroke development.

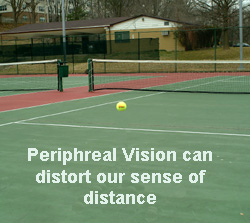

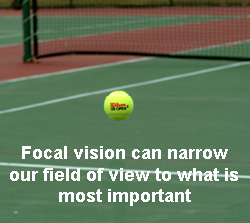

Emotion can distort what you think you see, it can change your sense of time and distance, it can block your ability to absorb what your instructor is trying to tell you (it can also block your instructor's ability to communicate to you effectively), and it can block your access to things that you do know (this is why some people are very poor at making good scores on tests when they know the subject). The first and worst fallout of emotion is its blocking effect. Fear, anxiety, mistrust, or even just being self centered can have a blocking effect on the learning process. Among these, fear historically has been the greatest barrier to the human learning process. One common respect in which fear obstructs learning is when you are doing drills in a state of fear (fear of approval, of failure, of embarrassment, etc) your internal clock becomes distorted in such a way that you are always moving too fast for the situation. In this case, you are overrunning the ball, swinging too soon, stiffening up, or otherwise performing well below your skill level. It is not uncommon for a student to come away from this experience thinking they haven't obtained any benefit from their lessons when in fact they would have the opposite impression if they were not fearful. The consequence of this experience can be that the student discards all that they have learned and regresses to a previous level. In this case they are effective stalled. A more serious situation occurs when the student is so fearful they simply don't hear anything the instructor is saying and resorts to just trying anything that comes to mind. We call this grab bagging. The opposite situation can occur when the instructor is lacking confidence in their ability to communicate a concept and begins shouting corrections that are unrelated to the student's performance. Both of these situations are common and arise from an emotional state.

A good deal of psychological discussion has gone into explaining the role of emotion in a tennis game. What may not have been stated clearly enough is that emotion can distort the senses, thus robbing the individual of their most important source of information about what is happening on a tennis court. If you don't have accurate sight or a sense of timing, you are, in effect, handicapped. In this case, it makes no sense to berate your performance or to attribute your performance to some metaphorical source such as choking (a case of imagined knowledge). Emotion is the second hardest element of the DICE problem set to solve. Only imagined knowledge is harder. In fact, emotion and imagined knowledge can work together to lock you into a viscous circle: Emotion can drive the creation of imagined knowledge which prevents you from performing to your expectations. This results in an emotional interpretation of your performance which leads to a further creation of imagined knowledge which can have emotional significance, and on we go. If this gets out of hand, you might find yourself wanting to break your racquet, or just give up tennis. Since emotion often biases or misdirects your interpretation of the facts, one must set aside all considerations of motive during practice or play. Any interpretations of any aspect of your performance can get a vortex started. It is even possible to get one started by being elated with early successes in a match or a tournament. The best rule of thumb is to keep the emotions out of your mind until after all objectives have been achieved. And then only allow yourself emotional views of your progress that are well tempered by the facts. Summary We have discussed the Big Four reasons (the DICE problem set) why one cannot just go out and hit the prefect stroke even if they have been provided perfect knowledge of how to do it. These reasons are

All of these factors contribute to why it takes 10-15 years to develop professional skills that can be developed in five years and at almost any age. By understanding the DICE problem set, and formulating a training program to minimize these problems, the time required to reach any particular skill level can be drastically reduced. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Ray and Becky Brown's article by emailing us here at TennisONE. Ray and Becky Brown are the founders of EASI TennisTM. The EASI TennisTM System is a new and revolutionary method of teaching stroke technique that can dramatically reduce the time needed to learn to play master, or any level, of tennis. To learn more about the EASI TennisTM System, click here. |

|||||||||||||||||||