|

TennisOne Lessons Ball Control - Direction Wayne Elderton No matter your level, success in tennis really comes down to one simple thing: “making the little round yellow fuzzy thing go where you want it to”. Manipulating the ball is the essence of the game. In the last installment (Ball Control – The unsung hero of tennis play), we learned that technique has a, ‘two-fold’ definition. Technique is both biomechanic (how the body moves for maximum efficiency) and ballistic (how the ball is controlled for maximum effectiveness). Playing tennis (or any game) is tactical. Making the ball do what it should allows tactics to be executed. Controlling the direction of the ball is foundational to success in tennis. Crosscourts, down-the-lines, and inside-outs are the ‘basics’ of tactical play. Even raw beginners can get points by directing the ball away from opponents. To have successful Game-based play, ball control is a necessity. Last installment, we also learned that it is not the biomechanics that directly determines where the ball goes, but the ballistics (Ball Control). The factors that directly control the ball are called the P.A.S. Principles (The Path, Angle, and Speed of the racquet through the impact point). Let’s look at the P.A.S. Principles and how they can be used to make us masters of directional control. “A” = ANGLE Each one of the P.A.S. Principles has it’s own unique contribution to controlling direction. The one I prefer to introduce first is the angle of the racquet at impact. Basically, wherever the ‘face’ of the racquet is looking, is where the ball goes. This simple understanding can dramatically improve your control and cuts through all the common misconceptions that confuse the issue like, where your feet are lined up, how your body goes, or where the follow-through should be.

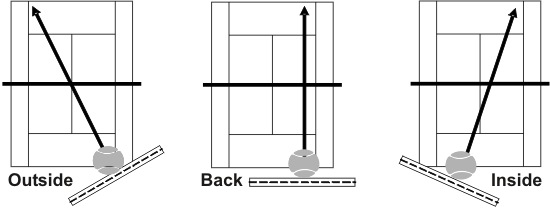

For a visual picture, imagine the ball has three ‘sides’ (see diagram). One can hit the ball on the ‘outside’ (sending it crosscourt), the ‘back’ (sending it straight), or the ‘inside’ sending it inside-out. Take a look at the two video clips of Roger Federer below. In Clip #1, he sends the ball crosscourt. In clip #2, he sends it down-the-line. Notice the impact points of both shots and the “side” of the ball he connects with for each. In my experience, getting a feel for connecting on the appropriate, ‘side of the ball’, gives players an immediate jump in their ability to direct the ball. This is the principle players should master first. Adjusting the racquet angle is the simplest and most effective way to direct the ball however, it isn’t the whole story. Two challenges make the Angle principle difficult to perform consistently.

Challenge #1: The circular stroke The difficulty with making the racquet angle correct, is that the racquet is in constant motion (as well as the ball received, and your body). If the racquet is swung in a circular path (very common when one is rotating), making it face your intended target becomes tricky. If the swing is circular, the racquet faces the target for a very short time, and precise timing of that that moment is problematic. Challenge #2: Angle of reflection It is important to realize that every shot has a ‘Reception’ phase (what we do to receive a ball coming to us) and a ‘Projection’ phase (what we do to send the ball toward the opponent). The reality of tennis is, the ball often comes to us at varying angles.

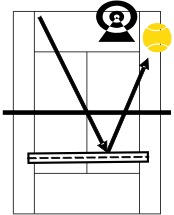

When receiving the ball, the challenge becomes a rule of physics called, “The angle of incidence equals the angle of reflection.” In simple terms this means that a ball approaching our racquet at an angle will ‘reflect’ off the strings at approximately the same angle. In other words, even though a player’s racquet face is ‘looking’ at the target, the ball may reflect elsewhere (Figure 2). “P” = PATH The solution to challenge #1 is correctly controlling the horizontal path of the racquet through the impact. Players need to make a ‘Hitting Zone” rather than simply a contact point. A hitting zone is the distance the racquet travels with the correct angle (towards the target). If the racquet is correct for a longer distance, the ball can be impacted anywhere in the zone and still be on track. Creating a Hitting Zone gives a stroke a margin of safety. The racquet path can be circular overall, however, when it passes through the impact point, it needs to straighten out towards the target. This principle applies, even when hitting with spin. To make the hitting zone, we do need to modify our biomechanics. The following mechanics help our racquet path so a hitting zone is created on groundstrokes and volleys:

The solution to challenge #2 (angle of reflection) is the speed of the racquet through the impact. Basically, if the racquet is moving slower than the ball the, “angle of incidence equals reflection” principle, will apply. However, if the racquet is moving faster than the ball, the path of the racquet will dominate the ball’s direction.

For example, many times a player ‘blocks’ their volley with a firm and motionless racquet. But, if an opponent hits a crosscourt passing shot (the player receives a ball coming from an angle) the ball may still reflect outside the sideline even though the player has their racquet looking at the down-the-line target. If however, they accelerated the racquet towards their target, the speed would send the ball down-the-line. On the other end of the scale, players can use the angle of reflection in their favor. If, they want to take pace off the ball and send an angle, they can decelerate the racquet and let it reflect off to the side. Dave Smith had a good analogy about this in his December 22, TennisOne newsletter article. He said to imagine a beam of light (the ball) reflecting off a mirror (your racquet). This will give a picture of what is actually happening. On most shots, players should make sure their racquet is going faster than the ball. This will ensure better directional control by minimizing any reflection angles. Accelerating the racquet through the impact minimizes a multitude of problems. All too often, players slow down their racquets for accuracy. This can actually have the opposite effect. As long as the racquet is on track, (swinging wildly fast is of no benefit) the speed will always help. Direction on the ServeFor serving, all the same principles apply. Of course, the ball is not being received from an angle (unless your toss is as bad as mine). Basically, the angle of the racquet at impact determines the serve’s direction. When sidespin enters the equation (slice) the ball will follow a curved trajectory (e.g. right to left for a right-handed slice serve).

Drilling Direction An effective and easy drill that I recommend for improving your groundstroke or volley directional control is the “Alley rally.” This drill can be done serviceline to serviceline to start and progress to the baseline. To perform the drill, rally to a partner using only one stroke at a time (only forehands, only backhands, etc.). Keep the ball inside the doubles alley. The alley lines give a great visual reference to help keep your hitting zone long and see if it worked. Once you get good at it, transfer the skill into play by simply imagining an alley between your impact and your intended target. For further training, any of the standard direction drills players have used for the last 50 years will help you improve. However, when using them, here are a few tips to get the most out of your direction training:

In future article I will continue this series by looking at each ball control and providing drills to help you master the PAS Principles and make you the most effective player you can be. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Wayne Elderton's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

|

Wayne Elderton

Wayne Elderton