|

TennisOne Lessons Ball Control - Distance Wayne Elderton This is the final installment of the series on Ball Control. During the series we have covered all the Ball Controls of Direction, Height, Speed, Spin, and now finally, Distance. The motto of the series has been: No matter your level, success in tennis really comes down to one simple thing: “making the little round yellow fuzzy thing go where you want it to.” Manipulating the ball is the essence of the game. Distance and Tactics Controlling space is a big part of tennis tactics. Putting your opponent in locations that are not an advantage and locating yourself in positions of greater advantage makes for a winning game. Space wise, a singles court is almost three times longer than it is wide. That means there’s a lot of potential territory to exploit if the Distance of a shot can be manipulated. “Hit it deep” is a mantra of most tennis coaches. The idea being, if an opponent is pinned far back into the court, it is very difficult for him to hurt you. Balls hit to you from way back have more distance to cover so they will likely be less powerful and possibly shorter. Controlling the distance of the ball also means the ball can be placed at the feet of a net-rushing opponent. Short angled shots are another way to put opponents in trouble. In other words, there are a good number of tactics available if one can control distance.

For players at the net, the use of distance becomes even more effective since, not only can they volley it deep, but the ball can be hit even shorter and with greater angle than would be possible with a groundstroke. Technique for Distance Control Just like in the rest of this series, the point needs to be stressed that tennis technique needs to be connected to tactics. Practicing “isolated” technique is not the most effective way to improve. Isolated technique is typically taught in the form of a specified one-size-fits-all stroke model (take it back like this, swing like that, and follow-through to here). It is movement for the sake of itself, and not related to playing the game well. Good technique should always make the ball do what you need it to. Good technique includes not only good mechanics (efficiency) but good Ball Control as well (effectiveness). The key to technical effectiveness is what happens when the ball contacts the racquet. This is the most critical moment in all of tennis. Distance is a combination Ball Control. It is made up of a recipe of three of the other Ball Controls, Height, Speed and Spin all combine to make a Distance.

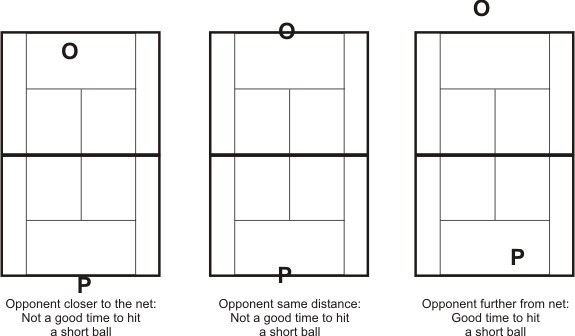

Sound complex? Just remember, it’s only rocket science! For most players, adding a little bit of all three (Height, Speed, and Spin) will be the way they control things. The big key is to understand that what you want to do determines which combination you choose. The key rule for determining when to hit short (a drop-shot) is: “Never attempt a short shot unless your opponent is further from the net than you are.” When is it a good time to try a short shot? (P=Player O=Opponent)

Receiving Different Distances Sending different distances is only one side of the story. Receiving variations of distance comes with its own set of challenges. When it comes to receiving deep balls, there is a misconception that stereotypes aggressive tennis as always taking the ball early. In the "age of Agassi," every coach had players standing inside the baseline hitting shots. Fortunately, coaching is more enlightened now. Moving back to hit a very deep ball is a necessary movement that all top pros perform.

Don’t let any coach try to tell you that when pros move back it is always a mistake and if they could, they would have moved forward to take the ball. If the ball is landing deep enough, top players would rather back-up, take the ball at a better height, and be able to take a fuller swing at it (which is still taking it early by the way). The timing isn’t as difficult and they can neutralize their opponent more easily. It is a purposeful choice, not a mistake. Agassi (I use him since most coaches use him as the ultimate example of hitting early) backed up a lot; however, he earned his aggressive position on the line frequently by making his opponent’s cough up weaker balls. Now, if they could have taken the ball at a good height by moving in, but let the ball drop because they backed up, that may have been a tactical error (but not always). The depth of the ball in relation to your location makes the choice of taking it early a smart one, or a poor one. A good player must learn when and how to back up and take the ball and, when and how to move forward and take it early. Both skills are required for top tennis. Standing inside the baseline doesn’t make one aggressive (especially if the depth of the ball disagrees), capitalizing on the proper opportunities to be up there at the appropriate time does.

For short balls, top players use a variety of footwork to get to the ball. The challenge is to move forward but ensure that your shoulders get sideways to load for the shot. To solve this problem (running forward but performing a sideways shoulder turn), we see right-handers jumping off the left foot and landing on the left, or stepping on the right foot (with a shoulder turn) and landing on the left. The thing recreational players can learn from this is to avoid the racquet-out-in-front, face-the-net, shovel-the-ball-up shot. Distance control isn’t just for groundstrokes and volleys. Serves that penetrate the service box give returners more trouble. Hitting totally flat and deep into the box is difficult because the "window of acceptance" over the net is small. In other words, if you hit a flat serve low over the net, it could land short. Hitting it higher might send it out. It is a very small difference in the net clearance. Most recreational players don’t serve that hard so their ball flies in an arc. When they start to serve harder, they hit it out way more than in. They become good servers when they learn to spin the ball, which allows for a higher net clearance, an arced trajectory, and still maintain good speed. Like the other shots, the secret to a deep serve is the combination of Speed, Height, and Spin. Find the combination that allows a solid serve that lands deep and is consistent. It is the balance that escapes most players (mostly because they don’t know what they are looking for). Distance Control Drills Many players practice drills that make them run from side to side; however, up and back movement is almost ignored. Here are some drills that help players both send different distances and receive them as well.

My hope is, that by taking in all the information in this Ball Control series, and practicing its on-court application, players can break out of the tendency to simply practice strokes and really learn how to play effectively by controlling the ball. That is the beginning of training with a Game-based Approach. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Wayne Elderton's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

|

Wayne Elderton

Wayne Elderton