|

TennisOne Lessons

Ball Control - Speed

Wayne Elderton

No matter what your level, success in tennis really comes down to one simple thing: “Making the little round yellow fuzzy thing do what you want it to.” Manipulating the ball is the essence of the game.

Click photo: Fabrice Santoro is a master at manipulating the speed of the ball. |

In this installment of the series, we will take a look at the Ball Control principle of speed. Often in tennis, it’s called ‘power’, and the terms are basically interchangeable. The reason I don’t prefer the word ‘power’ is that it usually conjures up images of strength, and using muscular force. Speed, on the other hand, gives the feeling of looseness and being relaxed, which is critical for successful tennis play.

In a Game-based approach (GBA), speed is an important concept in tactics. Sending the ball faster or slower allows a player to challenge an opponent’s timing. Just watch a ball speed master like Fabrice Santoro and see how changing speeds can be a weapon.

We learned in the last few articles that Ball Control is a result of the PAS principles. (Path, Angle, and Speed of racquet through the impact point). Let’s look at how the PAS Principles affect speed.

PAS Principles and Velocity

The ball we receive has a bearing on the speed we send it. If the ball comes at us faster, we can use it’s speed if we know how. If the ball comes slower, you have to work harder to send it fast.

Apart form the speed of the ball received, the main way to control the speed of the ball is by controlling the velocity of the racquet. What is the difference between racquet speed and racquet velocity?

Velocity is speed with a directional orientation. For example, if your racquet goes at the ball in a back to front path at 50 miles per hour, the ball will have maximum forward velocity. If however, your racquet goes the same 50 miles per hour but low to high, topspin will be imparted onto the ball. The result is, the forward velocity of the ball will be less.

In other words, if the path and angle of the ball are different than the direction you are sending the ball (hitting with any spin), the racquet won’t go as fast. If the path and angle matches the direction you are sending the ball, it will basically go with maximum speed.

Mechanics and Racquet Speed

Often, players get lost in the biomechanics of a shot. For example, on a serve they read about, ‘bending their knees’, ‘rotating their body’, ‘reaching up’, ‘snapping their wrist’ and even, ‘grunting’. All these things are fine except, if they don’t add to racquet speed, they add up to nothing. Any mechanics used to generate power must be geared to increase racquet speed and consistently control the Path and Angle. Not applying this principle can lead to movements that have no function.

On the other hand, biomechanics are critical to generate speed efficiently. In the first installment of this series, we learned that technique has a ‘two-fold’ definition. Ball Control is all about the ballistic component of technique. How the body moves is the biomechanical component of technique. Racquet speed is where the ballistics of technique meets the biomechanics.

What do I mean by that? Speeding up the racquet is a simple concept however, doing it with poor mechanics leads to inconsistency. Speed in tennis is never produced in isolation to the game. Tennis is not like baseball where one is trying to ‘knock it out of the park.’ If the ball doesn’t go over the net and land within the court lines, you lose the point. Even beginners can whack a ball with speed. It just rarely goes in when they do.

Ball Speed/Consistency Connection

For maximum success in tennis, a player must balance ball speed and consistency. For most players, speed and consistency are two ends of a continuum. Their mechanics make it an either/or choice. They either keep the ball in play or, they hit it hard.

Inconsistently bashing as hard as you can doesn’t lead to successful tennis. Players will sometimes try to develop this way hoping that one day, the ball will go in. It is possible some will find the way, but the vast majority will not.

However, the other side of that is just as problematic. There is such a thing as a, ‘quantity trap.’ Players hitting at slow speeds to get the ball in. Unlike the ‘bashers’ they train to keep the ball in play 20, 50, 100, 200 times in a row, hoping one day, it will go in harder. These players typically thrive at lower age/level divisions but can’t excel at higher levels.

Professional players have solved this conundrum. For them, speed and consistency are simply two sides of the same coin. The coin being efficient mechanics. They can hit hard and consistent. They have balanced how much risk to take to deliver maximum pain to an opponent, but remain high percentage. This is a concept I call ‘competitive consistency.’

All players should be trained to hit with maximum power. Don’t misunderstand me here. I didn’t say all players should hit as hard as they can, just have the mechanics to produce maximum speed when required. I would rather train a player to hit 10 balls in a row and then train to hit those 10 balls faster with higher quality, then faster yet, etc. than hit 50-100-200 in a row. Tennis points don’t last many shots (unless the players can only hit with little speed).

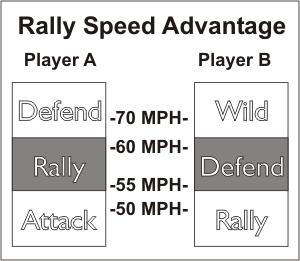

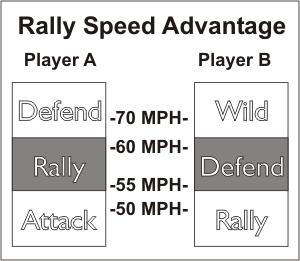

The player with a higher rally speed (consistently able to hit the ball harder, or take it earlier) will win the majority of the rallies in a match. Here is an illustration Canadian Head National Coach, Louis Cayer gives:

The rule of thumb is, the player with the higher rally speed will usually dominate the rally. For example, let's say Player A’s maximum rally speed is 60 mph and B’s is 50 mph. That means anything above 50 mph takes B out of his comfort zone. If A is rallying comfortably and in control at 55 mph, B is not in a rally phase, he’s defending! B will be under constant pressure to keep from giving up a weaker ball to A. His normal rally speed will produce attackable balls for A who can handle a much higher pace. To hurt A, B will have to hit far above his comfortable limit, which will most likely produce a wild error.

Racquet Rhythm, “The best of both worlds”

One of the key ways advanced players can balance consistency with speed is by adjusting their racquet rhythm. Racquet rhythm is when the racquet goes slow or fast in the motion. There are four basic rhythms:

- Same-same: (e.g. fast-fast or, slow-slow)

- Fast-slow

- Slow-fast

- Fast-slow-fast

Advanced players usually have a slow-fast or, fast-slow-fast rhythm on most groundstrokes and serves (unless they are modifying the ball speed like on a drop-shot, etc.)

By having a slow lead-up to the impact, the timing is simplified (facilitating a more consistent shot). By accelerating through the impact, the racquet speed is maximized. The slow-fast (or fast-slow-fast) rhythm gives the shot the best of both worlds; speed and good timing for consistency. Without the slow lead-up, the shot would become an uncontrolled ‘slap’. Without the acceleration, the shot would be a ‘push’ and may give an opponent an easy ball to attack. Just changing your rhythm can transform your groundstrokes and serves.

Santoro maintains racquet speed to ‘counter’

Santoro maintains racquet speed to ‘counter’

a hard ball. |

Speed Variations

Don’t get the idea that hitting with maximum power is the only goal of the Ball Control of Speed. There are three main ways to manipulate the racquet:

- Maintain Racquet Velocity: Keeping the racquet at a stable path, angle and speed is typically used to ‘counter’ a fast ball coming at you. By firmly maintaining racquet velocity through the impact, a player can use the speed the opponent provides to fuel their shot. Beginners should try to maintain racquet velocity on their shots to minimize variations and help control.

- Increase the Racquet Velocity: For maximum power, the racquet path needs to ‘level off’ and the speed increased. Speeding the racquet up will add power to the ball, unless the path or the angle of the racquet adds spin. In that case, accelerating the racquet will add more spin as it increases the rotation of the ball. To hit a spin shot hard, takes a tremendous amount of racquet speed.

-

Santoro speeds up the racquet to add power.

Santoro speeds up the racquet to add power. |

Decrease the Racquet Velocity: By slowing the

racquet, the ball can be slowed. If the path and angle are changed

(adding spin), the ball will slow even more. Controlling the racquet

PAS like this can ‘absorb’ the pace of the ball received. ‘Touch’ shots and ‘drop-shots’ are the most common use of this action.

Ball Speed Drills

Attack/Defend

This drill is good for accelerating the racquet (for power attacks), and decelerating or maintaining speed when defending or countering. The ‘defender’ starts by feeding an easy, arcing ball that lands just behind the ‘attackers’ serviceline and bounces up to shoulder height. The attacker goes for a power attack and the defender tries to survive. Whoever wins becomes the attacker. Play to 5, then switch roles.

For an added twist, the attacker can choose to attack with accuracy rather than power (a drop shot or an angle, etc.). Players will need to master all three racquet velocities to be successful in this drill.

Speed Training for Serves

Measuring speed can be a big motivator for improving your mechanics. Remember the rule: “To hit hard in tennis, you can’t try to hit hard.” It is always about smoothly coordinating your body and timing rather than muscular effort. The back fence can be used as the, ‘poor man’s’ radar gun. How close the ball lands to the fence (or how high on the fence it hits) on the second bounce gives you an approximate power measurement.

For example, if your serve’s second bounce lands at the bottom of the fence, tie a ribbon there and try to beat your ‘power record’ by serving it higher on the fence. By feeling the serves that go hard and the serves that don’t, you can zero in on the feeling you need to recreate when hitting a powerful serve. Of course, don’t count any balls that don’t land in the service box on the first bounce.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Wayne Elderton's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Wayne Elderton Wayne Elderton

Wayne is the Head Course Conductor for Tennis Canada Coaching Certification in British Columbia. He is a certified Canadian national level 4 coach and a PTR Professional. For two consecutive years he was runner-up for Canadian national development coach-of-the-year out of nominated coaches from every sport. Wayne has also been selected as Tennis BC High Performance Coach-of-the-year.

Wayne is currently Tennis Director at the Grant Connell Tennis Center in North Vancouver. He has written coaching articles and materials for Tennis Canada, the PTR, Tennis Australia , and the ITF. He is a national expert on the Game-based Approach.

For more information on the Game-based approach, you can visit Wayne Elderton's website at www.acecoach.com

|

|

Wayne Elderton

Wayne Elderton