|

TennisOne Lessons Effectiveness of Modern and Classical Approach Shots Doug Eng Power and quickness have fast become premium qualities for success on the tour. Lighter, more powerful modern racquets promote greater racquet head speed making aggressive hitting possible from almost any position on the court. Because of this power surge, players have less time to read and react to the ball.

One of the major technical changes in the modern game has been the approach shot. Years ago, in a slower game, court geometry and movement to the net were considered important for success at the net. Playing at the net was more valuable as baseline winners were rarer. The classic down-the-line approach shot allowed the attacking player to geometrically better cover the court than the crosscourt approach. The approach shot was frequently hit with some slice or fairly flat to keep the ball from sitting up high on the court. A low ball forced an opponent hit up on the ball making the volley easier. The approach shot also involved dynamic balance meaning a pro could efficiently move forward as the ball was struck. Efficient movement allowed pros to get to the net faster where the classic net game was highly effective. In the modern game, much of the classical game remains true. Approach shots that stay down low are harder to hit passing shots off. Geometry does not change and neither does the concept of covering the court better off a down-the-line. There have emerged, however, other options due to powerful groundstrokes. Players can hit passing shots harder making the volley difficult. Therefore, the modern option is to force the opponent to hit poorly. The harder one hits the approach shot, the more difficult the passing shot becomes. Many of the hardest-hit groundstrokes are hit off a loaded open stance. That means the weight is planted on the back foot and the stroke is rotational rather than forward through the ball. The approach shot becomes similar to the groundstroke in relying on rotation of the hips and shoulders to generate topspin and power. In the modern game, the approach shot is frequently struck in this stationary or static position.

Recent debate, most notably by Vic Braden, suggests that today’s touring pros have neglected the importance of dynamic movement. Braden suggests that pros could get to the net much faster using a stroke with predominantly linear movement. That is, the older classic footwork might promote more success by allowing a player to get at the net quicker. Logically, that is certainly true. The dynamic footwork allows the player to close the net more effectively. However, the static footwork allows a harder hit ball to pressure the opponent. Both have benefits, but which is better? If Braden is correct that the dynamic footwork can allow the closing player to hit better volleys, then we should most probably see some benefit in ability to win the point. On the other hand, if the static approach shot allows an easy winning volley, we should also see some degree of success in winning the point. Since it is a bit of comparing apples and oranges (that is, pace vs ability to close in quickly), an objective way of evaluating the approach shot styles is to examine actual statistics. A study of this year’s Wimbledon shows 90.4% of approaches were hit with topspin. Most of the remaining balls hit with underspin were with the classic slice backhand. Most slice backhands involved the carioca step or similar dynamic foot movement. The most commonly used approach shots in this study are shown in Table 1.

A number of different types of two-handed backhands were also struck quite similarly to the forehand (e.g., back kick or static). However, most pros chose to run around the backhand to play the forehand approach shot. In this table, the first three shots were almost exclusively hit with topspin and the last was almost exclusively with underspin or slice. The fact that there was remarkable similarity among the success rates of the first three major approach shots suggest that dynamic movement may not be as important as some teaching pros (e.g., Vic Braden) suggest.

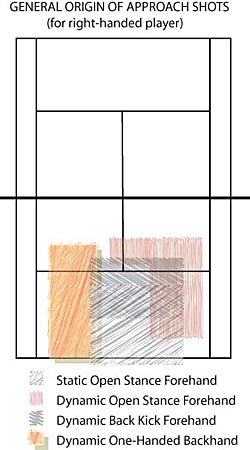

It is interesting to note that even among two-handed backhand players, the one-handed dynamic slice is a very popular shot especially on grasscourts. The one-handed dynamic backhand is statistically less successful than forehand approaches. A comparison of the two-handed versus the one-handed backhand does not show any significant difference with the sample (N=250 approaches). However, this study was not conclusive in comparing one-handed and two-handed backhands. Controlled Aggression It is remarkable that the touring pros in this study played the most successful shots most frequently. Perhaps they implicitly or subconsciously understood their chances of winning with different footwork. Tournament players should learn to play most or all of these shots. The static open stance forehand approach is easy to play if you have a big forehand. Just play your big groundstroke. Obviously, you must be set up and in a well-loaded (weight on the back foot) position. Pros most frequently play this shot from from the middle third of the baseline (see court diagram). Pros use this on short and deep balls (even at the baseline). The pros use a “rip and rush” technique which means they hit the big forehand and look immediately for signs that the opponent is in trouble. So if a pro knows he hit a very good shot and the opponent is running hard, the pro will close towards the net. The concept is simple, pound your opponent hard, anticipate the poor return, and close in to volley. If you don’t have a big forehand, the static rotational approach should not be used frequently. Of interest was the infrequency of errors on the approach shots. An unforced error rate of 3.6% occurred in this study. Although pros are hitting aggressively, the approach shot may be highly successful compared to groundstrokes because they are much less likely to be hit from under pressure and more likely to involve a position in which the hitter is easily set up. Recreational players make Many more errors from positions easily set up because they try to hit beyond their limitations. Pros are more likely to play their approaches from a posture of “controlled aggression.” The back kick forehand is usually hit from the middle third of the baseline (see court diagram) on a slightly short ball, although some pros (notably Justine Henin-Hardenne) use it from the outside deuce (or forehand) third of the court. This stroke is somewhat more difficult to play than the static rotational forehand. You must set up in a square stance meaning your feet are parallel to the sideline. As you strike the ball, lean slightly forward into the ball and let the back leg (right leg for righties) kick up. You will get your weight into the ball to add pace and also be able to move slightly forward. You will note that as you lean in and kick backwards, you will have a tendency for the front foot to hop a little forward.

The open stance dynamic forehand is most often played from up closer to the net and also to the forehand sideline (see court diagram). In fact, anytime you are near the deuce court sideline (for a right-handed player) you should usually try to hit off an open stance for faster recovery. On a short ball or a ball fairly close to the sideline, you will find yourself naturally moving harder to get to the ball. A simple and most dynamic variation of this approach is to almost walk through the shot. As you stride forward with the right foot (assuming you are right-handed), let the left hand move forward across your body (parallel to the net) to turn the shoulders. As you strike the ball, your left foot (assuming you are right-handed) should slide forward. It is actually quite similar to walking. Think left hand – right foot forward and then right hand – left foot forward. This shot was traditionally hit with underspin but today is usually struck with topspin or relatively flat. This shot is usually not hit as hard as the static approach shot but it allows you to close in faster. In the past, the dynamic forehand was frequently struck with slice or underspin. Today, it is usually hit with topspin. In the carioca one-handed backhand, as you move the racquet through the contact point your left foot will slide behind the heel of your right foot (if you are right-handed). Like the open stance dynamic forehand, think of walking where the right hand and left foot move forward together. To get underspin, use a continental grip which makes it easier to go from high to low on the swing.

If you are not a big hitter from the baseline, the dynamic approach shots are valuable for your game. They allow you to close in and play good midcourt volleys. If you have the big groundstrokes, however, rip and rush from the static position. The table above shows that dynamic footwork may not be critical among touring pros. Keep in mind that touring pros have more effective midcourt volleys than recreational players and pros are often much quicker to close to the net than recreational players. On the other hand, it may be more effective to hit hard with pace and topspin to limit your opponent’s time and ability to control the ball. Earlier this year, at NCAA quarterfinals, a player I coached was playing against the eventual champion. She was trying to approach both off a backhand slice and off a topspin forehand groundstroke (which might be the best in NCAA Division III). Her opponent clearly passed her much better off the slice even though it was low and deep. However, her opponent could not control the placement of her passes off the big topspin forehands. Obviously, I suggested to her to not use the slice approach and use almost exclusively her topspin forehand approach. In the next issue, we will examine the question of depth and direction on approach shots. Specifically, we will look at whether pros wait for short balls, whether depth matters on approach shots, and the directional placement of the modern approach shot. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |