|

TennisOne Lessons Connecting the Body Doug Eng EdD, PhD There are many ways to hit a tennis ball. Some ways are better than others. A good stroke at a beginning tournament level won’t work at the satellite level. Some people are very consistent with short swings using big racquet heads. Often we call them pushers. Others take long, fluid swings which give more power but less consistency. Then there are those players who look great in practice but tight and awful under the pressure of match play.

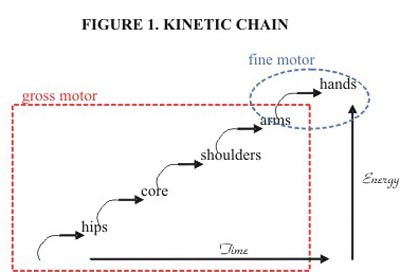

I teach students to connect the body when they hit groundstrokes. That means they should experience a swing where the legs, hips, torso, shoulders, arm, and racquet all work together in synergy. When the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, we get synergy. A well-coordinated swing has synergy. If you swing with a disconnected body you lose power and efficiency; your legs or your hips may not be working effectively. Sport scientists refer to this body connection as the kinetic chain, where the body parts work together as shown in Figure 1. An effortless, powerful swing connects the body in the kinetic chain. In this article, we will look at the general concept of using the body to swing the racquet. Specifically, we will address how the core and torso are used, why some people use the body more efficiently than others, and how perception and anxiety can undermine a great swing under match pressure. During stressful matches, people often find their muscles get tight which limits fluidity in their strokes. When this happens, smaller muscles or fine motor movements tend to control the stroke making it much less effective. We will also look at why many people swing primarily with the arm or hand rather than with the body. It is important to note that tennis is a mind-body experience and even if you physically have great strokes, your mental attitude can still undermine them. Here, we’ll look at boththe mental and physical sides of producing a stroke using the body. The idea is to use your body more effectively to generate a more powerful swing. And finally, we will look at some techniques and drills you can use to improve the way you use your body on groundstrokes. Gross and Fine Motor Movement

Sports educators and scientists categorize movement as either fine-motor or gross-motor. Fine motor movement uses smaller body parts such as the fingers, toes or lips. Gross motor movement coordinates the torso, legs or arms. People who are pre-dominantly fine-motor skilled might write or play the piano better. They may also tend to be consistent pushers using short swings generated with the hands. People who are predominantly gross-motor skilled might be better coordinated at jumping or throwing a ball. To get more power, a tennis groundstroke should utilize gross motor skills. For the most part, everyone has both fine and gross motor skills but pushers with short swings underutilize the body. You might ask whether there are situations where fine motor movement plays a more important role in tennis. The answer is yes, when 1) changing the grip, 2) adjusting the racquet face to the contact point, 3) touch or drop shots, and 4) when you have less time such as during volleys or emergency shots where the lower arm (from the elbow to the hand) and hand are major components of the swing. But even on most volleys and emergency shots, you will have some gross motor movement. Let’s consider three reasons why a tennis player might use predominantly fine-motor movement:

Neuromuscular Wiring

Everyone’s neuromuscular functioning is wired differently. For example, one person might use his left hand to swing the racquet but writes with his right hand. This right-left dichotomy is called laterality. If you primarily use your right hand, arm, leg, and foot, you have right-side laterality. If you use some left side and right side, then you have cross laterality. Some people who have cross-laterality may find it difficult to properly coordinate swinging a racquet. Novices often use short swings since their primary objective is simply making contact. As the swing and timing become more automatic, the player may focus on racquet head speed and tactical patterns. However, if learned improperly, a flawed swing might creep into an advanced game. For example, some 4.0 level players use a forehand rather than a continental grip for the serve. In the video above, we see two players: the first uses the hands too much to return the ball, the second uses an arm swing to hit the forehand. When learned improperly, a stroke becomes imprinted upon your neuromuscular functioning and, after many repetitions, it becomes difficult to unlearn. Sport scientists have used esoteric laboratory techniques such as transcranial magnetic stimulation to examine neuromuscular activity and brain functioning. For each specific task, there is a unique neuromuscular pathway. So, as much as your tennis pro says serving is like throwing a ball, they are never quite the same. Your brain will not use the same neuromuscular pathway to hit a serve and throw a ball. The same is true for a flat serve and a slice serve. A subtle difference requires a different neuromuscular pathway. PET (positron emission tomography) scans have demonstrated that the brain activity for an expert player is different from that of a beginner. Brain activity also differs with the nature of the task (e.g., cognition or long-term memory).

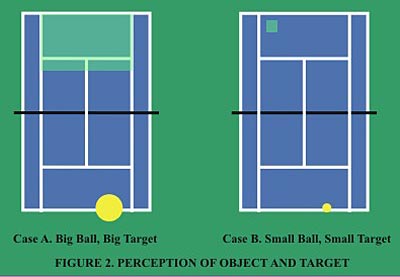

Perception of Precision When you need to use the elevator, you might walk up to it and press with just one finger. If you ever played the old game twister, you might put a foot on one small spot. On a narrow balance beam, gymnasts take small steps. Imagine if the elevator button was a yard across. Would you still push it with one finger or would you press it with the heel of your fist? Elbow? Or just lean your body against it? Or if the twister circle was only three inches wide, would you try to put only a toe on the spot? Or how much faster would a gymnast move if the balance beam was ten inches wide? What makes many of us avoid using the body to swing the racquet is often perception of a) object size and b) target size. I define object as the tennis ball and target as to which part of the court (or space over the net) you are aiming. If the object or tennis ball was one foot in diameter, the perception of making contact would significantly change. You would probably focus more on making a beautiful stroke rather than making contact. Your movement would not need to be as precise and therefore, you would tend to utilize gross motor skills more. In sports psychology, one of the characteristics of being in the zone (or ideal performance state) is visualizing the ball as very big. If it is perceived as big, you would find yourself comfortably and confidently taking bigger, more powerful swings. When you are playing well, that is what happens. When you strike a ball, you may choose a target in the court or above the net. If you aimed for a smaller target, you might find yourself taking pace off the ball or shortening the stroke. The perception of a smaller target may induce you to utilizing finer motor skills. Changes for some players may be small (e.g., slightly slowing down the swing) but they will exist.

In Figure 2, we see two extreme cases. In case A, it is easy to be confident and strike the ball well. In case B, if you perceive the object ball as very small and your target as small, it is easy to get tight and use your fine motor muscles only. There is small advantage to challenging yourself to aim to small ambitious targets since your focus and accuracy might improve significantly but with an inexperienced player, it is easy to use inhibited strokes. Small targets are useful once a tennis player has a confident, good grasp of technique and can confidently hit with speed and accuracy. Studies actually show better players perceive the ball as bigger or targets as bigger! So a good player who uses a full, fast swing often perceives the ball as bigger or the chosen target as huge and easy to hit. What does this mean? It is an issue of mind over body. For example, if you develop the negative perception that it is really bad to double fault, you may tighten up and have the tendency to push the second serve in. It’s your perception of target and consequence or outcome. Instead, pretend the ball is big and the targets are big and easy to hit. Fooling the mind helps release it from fine-motor movement used for fine, precise activities. So if you allow yourself to make a couple double faults per set, you may find it less stressful and your serve might be more relaxed. Anxiety Negative perceptions often contribute to anxiety which also affect the way we hit the ball. An anxious person may find a certain situation stressful where another person in the same situation may feel carefree and relaxed. Anxiety interferes with both gross and fine-motor skills. Gross-motor skills tend to be reduced to fine-motor skills as the anxious player feels the feet get wobbly and the knees lock up. Many beginners hold the racquet too tightly as they find making contact and getting the ball over the net a challenge. They become over aroused or overexcited as stress interferes with the body. In addition, the beginner lacks automaticity and tends to over-think about the striking process. Stress limits fluidity of play and promotes fine-motor skills even at high level. Therefore, even at the open division, we might find pushers and moonballers since these tennis players will resort to fine-motor movement during stressful moments. They are attempting to control their arousal. And if the player tries to stay with full swings, even the fine-motor skills negatively affect the stroke. The hands may not control the racquet face finely and errors begin to creep in. Try threading a needle when you are really upset; your motor skills will be off. Anxiety is affected by negative perception of success and outcomes. An outcome-oriented person is focused on the result of the rally (on not making a mistake) and will tend to use finer motor skills than the task-oriented person. A task-oriented

player's goal tends to focus on development rather than winning the

point. As a result, he will find making errors and losses are

acceptable in trying to develop a new technique. Some of us learn tennis ineffectively and find it difficult to unlearn. Beginners are easily over aroused and focus on the contact point; their strokes tend to be short and tense. Beginners primarily rely on the use of the hands rather than the hips. The proximal body parts to execute a certain skill become highly relevant. For example, a beginning dancer may only move the feet as the most relevant and proximal body parts and not the hips or hands. Likewise, the hands are the most proximal parts of the body to racquet and the ball. If you are someone who gets tight and needs to develop a more fluid body swing, try ignoring the result of the rally. Drop all expectations of consistency as you feel the stroke. Reevaluate your goals or expectations. For some of us, this thought can be tough since we are so glued to the idea that solid contact must be made with every ball and all balls must bounce in. Sometimes, to step forward, you might need to step backwards and reshape your thoughts and behavior. So don’t even pay attention to where the ball is going instead, try to feel your stroke. If you have trouble ignoring the outcome, try hitting the ball in a parking lot with a friend or off a wall. That eliminates the lines and the net, thereby helping you reframe your goals and focus. Bounce-Hit Exercise The classic bounce-hit exercise is a great way to reduce stress and promote focused breathing. Practice saying “bounce” when the ball bounces on your side and “hit” as you strike the ball. It gets your timing and rhythm down, it gets you to breath rhythmically, it promotes relaxation and fluidity, and it prevents your mind from over-thinking. In zen philosophy the koan is a saying that confounds rationality so you can’t analyze it but yet you can intuitively grasp it. Getting very tuned into a “bounce-hit” koan gives you a fluid, rhythmic state. Saying ‘bounce-hit” gets you to do very little thinking and lets your body act without the mind. In such state, it is easier to use the body correctly rather than using the hands or arms only. Core Rotation In tennis, the development of good rotation around the core is essential for the creation of angular momentum. Below are three exercises to help you to develop core rotation: Torso Twist Stand with your feet shoulder width apart on the baseline and knees comfortably bent. Start slowly rotating at the waist to face either sideline, then back to the net and then face the other sideline. Some people like to hold out the arms or keep the elbows out away from the body. You may use your elbows to help turn you side to side. As you get more comfortable, pick up speed and flex the knees lower as you turn.

You can also do the torso twist exercise holding a gym bar. Again rotate trying to make the bar parallel to the sideline on each turn.

Medicine Ball Medicine balls are great for building strength and core rotation. For this exercise, you should use a ball that weighs between 4 and 15 pounds depending on your size and strength. With a friend, practice tossing the ball to each other using a shoulder turn as you would do on a real stroke. Use both forehand and backhand techniques. It is not as important to see how far or hard you can throw it but how much you can fluidly rotate into the backswing position holding the ball. Two-Handed Forehand Using the arms together generally promotes greater use of the hips and core. Some people hit the two-handed backhand better than their forehands. They are able to develop a more consistent striking action due in part to both hands stabilizing the racquet head at contact. However, the coordination of the arms together also promotes better use of the hips and core. Using one hand makes it easier to escape with using only the arm.

Practice hitting with a two-handed forehand. Start off with mini-tennis since you don’t have to run as much and you can make an easy, slow swing and get the feel of the hips and shoulders rotation. Stroking With a Trapped Ball Below is a great progression that stresses using the body, specifically the hips. Trap a ball under the armpit or elbow and take your racquet in the backswing phase. Note you can’t extend your elbow away from your body as the ball will fall out. Then practice swinging at another ball (you can drop it and strike it or have a friend feed you) without letting the ball under the elbow fall out. It’s tricky, but you will find your hips rotating forward in order to hit the ball. Next, do the same and place the ball under the armpit or elbow. Again, self-feed or have a friend feed you. This time, as you strike the ball, you may let your arm follow-through to the opposite side of your body. That is, use your normal follow-through. The trapped ball will fall out after you hit the fed ball.

Summary It is important to note that technical aspects of your game often have a mental component. You could choose to solely work on physical or technical exercises to hit the ball using the body. However, addressing the mental aspects is highly important. Chances are that some mental factors may be limiting your level of play. You might get too excited about playing, which can cause you to swing harder and your muscles to tighten. No matter how much you work on a skill, if you lack confidence using it, the stroke is likely to break down under pressure. The fact is, some players have very clean strokes but don't play well because they don't understand how to play points under pressure. Ultimately, you want to feel a gross motor movement and trust your ability to strike the ball. Your perspective on what you want to achieve, such as goals, can often affect how you play. For example, if you focus on the task, technical skills, or performance, you often allow yourself more freedom to hit the ball without negative stress. Focusing on the outcome can limit how you develop your technical skills. Chances are you already have strokes you are comfortable with but know you might be able to improve. Reframing your perspectives are paramount to improvement. Get yourself out of your comfort zone if you want to improve your technique. That is, be willing to try new things and forget about making contact and getting the ball in the court during a couple of practices. When playing next time, be aware of your breathing and your stress level. Visualize the ball as big to feel confidence as you develop a more fluid swing with the body. Then try the physical exercises and experience synergistically your body stroking the ball. Good luck experimenting with a better stroke! Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |