|

TennisOne Lessons Modern Directionals, Part 1 Doug Eng EdD, PhD Groundstrokes tactics have always been a foundation in tennis. Classical groundstroke tactics have emphasized depth with crosscourts and down-the-lines as two principle directions. Combined with pace and spin, these are tactical variables. However, modern technology — with advanced racquets and strings, and the evolution of athleticism and technique — has dramatically changed the game. At the pro level, we see Nadal and Djokovic scramble side to side in tough, long rallies and then do it again point after point. Professionals are able to apply more topspin which increases the ability to use short angles with deep drives. In part, slower courts on the tour have helped give more time to set up and stay in the rally. Lateral movement inside and behind the baseline has always been a major part of the professional game but recently it has become more demanding. In effect, the court has become wider although depth remains important. Even average club players can hit harder with more spin and pace. Net play has become less common as players have moved to more western grips and two-handed backhands which promote the heavy baseline game. These heavy groundstrokes and passing shots make net play more difficult. But even if a player chooses not to go to the net, taking the ball early inside the baseline offers significant advantages over playing several feet behind the baseline. Time for the defender is reduced and the offensive player inside the baseline has more choices. One could think of this game as an aggressive baseliner’s game but it is much more also a part of the modern all-court game. There are some fundamentals that never change, however, as offense is still primarily dictated from inside the baseline. Playing at the net is still a primary way to finish and win points. From defensive positions, it is still a fundamental tactic to play high and deep rather than low. Crosscourts, not down-the-lines, are still the basic geometric shots.

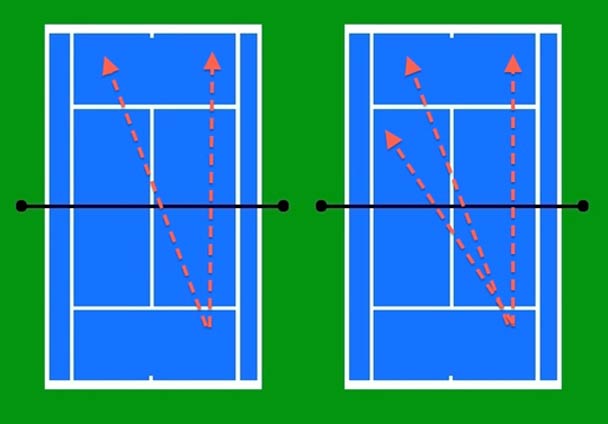

Figure 1 shows the classic directions in tennis and the modern directions in tennis. These include the basic crosscourt and down-the-line shots. Every competitive player is proficient with these two directions. As a player improves and masters topspin, the angled shot becomes a third option. Note in either diagram, the origin of the arrows (where the hitter stands) starts inside the baseline. They represent three offensive directions where the hitter can stand slightly inside the baseline. They can also be used defensively but for now, we will focus on offensive directions. Of course, a fourth shot, the inside-out forehand is a variation of the crosscourt. One way of understanding the directional choices, is to consider your primary or starting direction as the deep crosscourt. Assuming your opponent returns crosscourt, you have three choices: going back at the same spot with another deep crosscourt, trying to change direction with a down-the-line or opening up the court more with an angle. The angle is the hardest choice since the target is smaller. You only need to change direction with the down-the-line or crosscourt but angles demand additional spin. placement, and finesse. Often players just try return crosscourt since they feel it is less risky and more comfortable: e.g., waist high balls at the baseline going consistently in and crosscourt. We often assume the crosscourt rally is neutral. But consider a crosscourt rally where you like your forehand but your opponent likes the forehand too. And consider that your opponent’s forehand is better than yours. Do you persist with the crosscourt forehands? If you continue crosscourt and hit a bit shorter or softer, your opponent gets the first strike with a better shot. Even with a deep, solid ball, you are not moving your opponent. Hence, you are grooving your opponent’s best shot. Certainly you feel comfortable but your opponent also feels confident. So solid crosscourt rallies don’t always make sense. How can you change it? You can change the spin to slice, throw in a high, deep ball, or change directions. If you change direction with a down-the-line shot, your opponent has to run over to the weaker side. Most of us are coached into thinking the down-the-line shot is riskier. But consider your opponent must also make that shot on the run with a weaker shot. In addition, you can play a high, safe shot down the line with plenty of margin. Or, if you've mastered spin and feel, the angle becomes a viable option. Angles are important if you feel you are the quicker player or if you play the wings better than your opponent. The closer you are to a sideline, the more likely you can hit an angle. In doubles, with the wider courts, angles become even more important.

Tactically, many players don’t evaluate their opponent’s strengths well since they are preoccupied with playing their own game. Tennis, however, is a two-way street where you are pitting your strengths against your opponent’s weaknesses. Better players know how to stack their cards. Consider another way of looking at tactics and decision-making: ask yourself, do I want to continue this crosscourt rally, can I open the court more, or should I go at the other side which might be weaker? Hence, we see pros often try to play the weaker side of the opponent. That is more often the backhand side than the forehand side. The tactic of using the inside-out forehand against a backhand is a commonly used tactic at the advanced level. It’s strength against weakness. Hence, consider when should you go at the weaker side? This is where modern directionals get interesting. In a preliminary research with right-handed players only, it was found that the crosscourts in the ad court compared to the crosscourts in the deuce court were more frequently played. Since the majority of players are right-handed, the ATP pros are playing the backhand rally more often or hitting inside-out forehands to the backhand. Or working their opponents backhands. Or avoiding the bigger forehand. Consider a pro getting a forehand to hit in the deuce court. Sometimes the pro will prefer a down-the-line response to the backhand rather than a crosscourt to the stronger forehand. Sometimes we think the down-the-line is a low-percentage aggressive shot but often it is another shot to the weaker side or to keep the opponent moving. Therefore in the deuce court rally, a pro will more often go down-the-line rather than crosscourt compared to the ad court rally. Of course, the exact details may vary depending on the individual players strengths. Regardless, the ad court diagonal is more frequently used than the deuce court diagonal for many touring pros. It’s hard to play the modern directions unless you practice. So for starters, here are a couple of drills. DRILL 1. The Three Directional Feeding Drill The three directional feeding drill is shown in Video 1. It is a basic starting point once you get comfortable with using topspin. Have a coach, pro, or friend feed you balls as shown in the video. You may add scoring for each successful shot. The angle might have additional scoring for a wider shot.

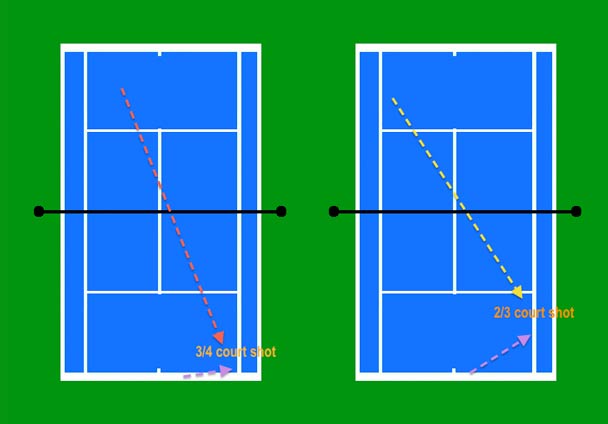

DRILL 2. The ⅔ and ¾ Court Shot Drill This drill is shown in Video 2 and also in Figure 2. A shot played from inside the baseline through to the other baseline is sometimes called a ¾ shot since it travels nominally ¾ of the court before bouncing. Note the ¾ shot is played inside the baseline and can be hit hard and flat. You are driving the ball through the court crosscourt and over the opposite baseline. Therefore from contact to the opponent at the baseline, the ball travels about ¾ of the court. If you angle the ball wider to the sideline, the ball leaves the court in less distance. Let's call this angle shot a ⅔ court shot since it's often played from inside the baseline to the sideline rather than a baseline to baseline shot. More accuracy and topspin is needed on the ⅔ court shot. The drills in Video 2 show three ways to practice these shots: one-on-one, with a negative target (that you avoid), and finally two-on-one.

To give yourself a chance at better consistency and better baseline tactics, use both drills regularly. Keep in mind that you are going for consistency and placement. You’ll find your baseline game will improve steadily with play. In future articles, we will discuss specific baseline patterns.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng

In addition, Doug has written over 70 tennis articles and has been translated into several languages. He consults in mental and physical training and researches in technical and tactical analysis. He has received many awards including most recently the 2012 US Olympic Committee Doc Counsilman Award for his work in tennis. Doug is a member of HEAD/Penn National Speakers Bureau. |