|

TennisOne Lessons Modern Directionals and Anti-Directionals on the ATP Tour Doug Eng EdD, PhD Baseline play has always been a popular discussion of tactics. Directionals are taught at the club, advanced junior, and collegiate levels. But much of directionals is guesswork and lack quantitative data. Very little research has actually been done on baseline tactics. Today, we see analytics at the Grand Slam events as IBM accumulates statistical data. Several years ago, I did a directional analysis of WTA touring pros. In this article, I will present research on ATP directionals. In my last article, it was established that ATP touring pros use the ad court rally as the neutral rally and to avoid the forehand weapon. The majority of ATP pros have stronger forehands than backhands, therefore, it makes sense that touring pros use the backhand-backhand ad court rally. It was also established that variety is more prevalent on the ad court side with the topspin backhand, slice backhand, and inside-out forehand.

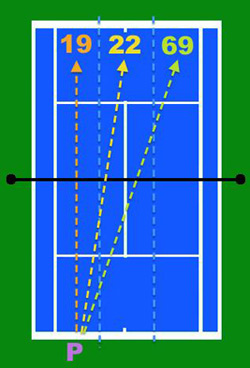

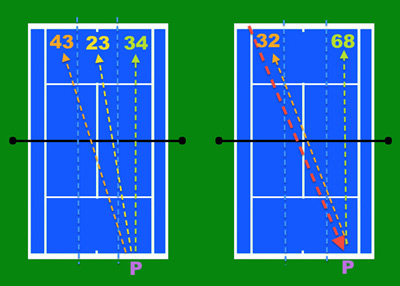

For this article, only right-handed ATP touring pros (Djokovic, Murray, Federer, Gasquet, Del Potro, Ferrer, and Hewitt) were studied. Second, only baseline groundstrokes were examined. Third, results are only for hard courts and indoors courts, excluding clay or grass court results. What follows are some interesting tactics worth considering for your game. Neutralize with the Backhand Crosscourt Rally Crosscourts are always more prevalent than down-the-lines, for all players whether club players or touring pros. When faced with a backhand from the outside ad court lane, pros were three times more likely to play crosscourt as opposed to down-the-line. Specifically, in Figure 1, the ATP pro went 69% crosscourt and 19% down-the-line with the remaining shots into the middle third of the court. From the deuce court lane, the forehand crosscourt was also the most frequent choice. But of all crosscourt rallies, 88% were in the ad court and 12% in the deuce court. In other words, the ad court crosscourt exchange was eight times more frequent than the deuce court rally. The lesson here is use the weaker crosscourt side as the neutral rally. Dictate with the Forehand Weapon Figure 2 shows the forehand deuce court patterns with three lanes. On the left of Figure 2, forehand crosscourts made up 43% of total shots, significantly less frequent than the backhand crosscourt (69% in Figure 1) from the ad court. Only 12% of crosscourt rallies occurred in the deuce court; pros were not content with driving crosscourt to the forehand. Overall, 52% of groundstrokes were forehands so there was still a preference to hit forehands (by running around the backhand).

From the outside deuce court lane, pros actually played the three lanes in the ratio 43/23/34, where the values are in percentages (e.g, 34% down-the-line). Compare that with a random 33/33/33. Clearly, most pros try to move the ball around with the big forehand but avoid repeated rallies with the opponent’s forehand. Hence, the deuce court and ad court rallies differ. The lesson here is learn to move your opponent around with your weapon. Not only hit to the weakness but keep your opponent off balance and look to open the court. The idea here is to pit your strength against your opponent's weakness. Changing Directions with the Forehand Clearly the forehand is being moved more than the backhand. One of the basic tenets in classical tactics is only change directions when you have a ball sitting in your strike zone. Instead, we are often taught 1) changing directions is more difficult and hence should done less frequently, 2) crosscourts are safer since they use the longer diagonal and 3) are hit over the lowest part of the net. Therefore, when faced with a pressuring crosscourt, it is considered wise to avoid changing directions and return the ball back crosscourt. Therefore forehand-forehand crosscourt rallies should be a reasonably significant part of the game. But as we saw, that is not the case. The right half of Figure 2 show responses after an opponent just hit a forehand crosscourt (red dotted arrow). If facing the choice of going crosscourt or down-the-line, ATP pros elected to go 68% down-the-line. In other words, they didn’t follow conventional thinking about the down-the-line being riskier. The 68% down-the-line response is an astonishing number which goes contrary to current tactical practices. Perhaps what we are learning from teaching does not apply at the elite level. We must keep in mind that the ATP game is about first strike. If you blink, you can lose the rally. If one pro gives another pro one too many chances, the point is usually all but over. The pace and accuracy of the groundstrokes is well beyond the skills of recreational players. Less skilled players don’t have the accuracy of touring pros. Therefore less skilled players may not be able to move the opponent as well as touring pros. However, a balancing factor can be the player’s foot speed. Pros move better but need to move faster as the pace and accuracy of the rally forces them to cover more court quickly. By comparison, a simple rule for basic recreational players is to play the ball high over the middle of the court. A wide shot will frequently force an error as recreational players move slower.

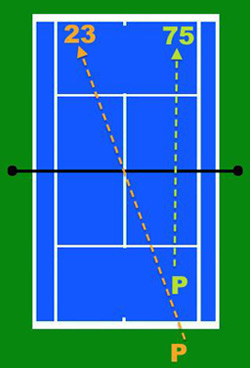

Court positioning of the players were also recorded. A majority of shots (68%) were taken slightly behind the baseline (2 foot to 8 feet). Only 15% of shots were taken inside the baseline. On a crosscourt deuce court rally slightly behind the baseline, ATP pros were slightly more likely to go down-the-line versus crosscourt. The pros actually changed direction an astonishing 77% of the time. That means 23% crosscourt (see Figure 3). Therefore, from a neutral position or even slightly defensive (behind the baseline), pros continue to mix up the forehand directions. However, when moving on top of the baseline and inside the baseline, ATP pros were much more likely to go down-the-line. About 75% of the shots hit from on the baseline or inside went down-the-line as shown in Figure 3. That suggests, on the defensive forehand, ATP pros mix up shots and change directions. They don’t simply go crosscourt on the defensive. Apparently, ATP pros understand that hitting to an opponent’s strength from a weak position is not a winning proposition. Therefore, their strategy is to continue moving the opponent and mixing up the shots. The down-the-line to the weaker side may supposedly be a lower-percentage shot by classical directionals but tennis isn’t just about keeping the ball in the court. It is also about taking your opponent’s attack away and keeping your opponent off balance. Hence, a smart neutralizing tactic is hitting a looping forehand high down-the-line to the backhand. Inside the baseline, the ATP pros went predominantly to the backhand. When in a position of strength, they went to the opponent’s weakness. It is like a predator sensing the kill. A prime example of how players go to the weakness is the modern approach shot which is often the inside-out forehand to the backhand. Classically, the approach was hit the down-the-line but that does not create as much movement. For aspiring players including fairly highly ranked juniors and adult competitors at the 4.0 level or higher, it is strongly recommended to reconsider directional tactics. The Inside-In, Inside-Out Game The inside-in inside-out is a common forehand combination for creating ball movement. It uses the player’s forehand strength (instead of the backhand) to dictate play.

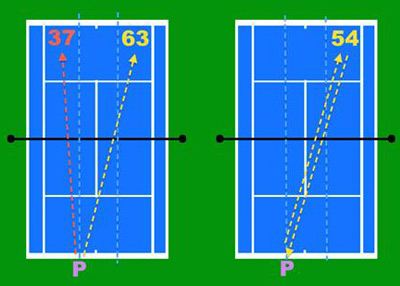

Figure 4 shows results of analysis of how the ATP pros used this combination. If having to choose between either shot, the pros chose the inside-out 63% of the time. That means the ATP pros would rather predominantly hit to the opponent backhand (inside-out) rather than the forehand (inside-in) by almost a 2 to 1 margin. However, the inside-out was often used similarly to a backhand crosscourt. That is, during the ad court exchange, players more often opt to hit the inside-out rather than a backhand crosscourt. Or another way of looking at it, the ATP pros usually (54%) maintained the ad court rally using the inside-out (Figure 4 right). Instead, the inside-in was used predominantly in changing directions. However, if the ball came from the ad court, the pros preferred to hit inside-out 66%. According to directional theory [Wardlaw in Pressure Tennis, 1990 Human Kinetics], it is more natural to change direction with the inside-in than to go back with the inside-out. But the pros didn’t normally try that but preferred to hit to break down the opponent’s backhand. Overall, 89% of the inside-ins did involve a change of direction to break the ad court rally.

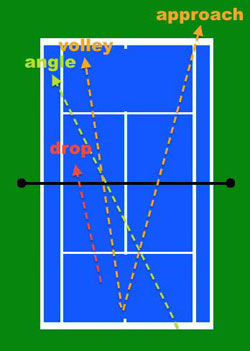

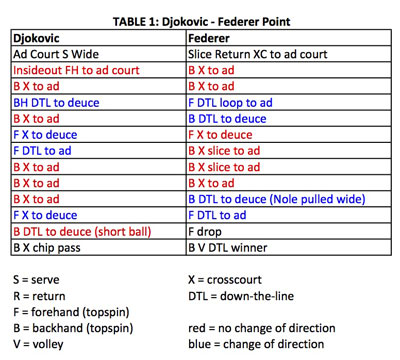

Make the Court Bigger As mentioned, ATP pros change directions more often than we think. For example, off a forehand crosscourt, we found ATP pros were 77% likely to change direction. Therefore, the pros are attempting to make the court bigger. Another way of making the court bigger is to use angles instead of depth. However, as much as modern polyester strings promote heavy spin, only 7% of all groundstrokes were angles (if we define an angle as a ball that crosses the sideline at least halfway between the baseline and service line). The frequency of using of angles fall somewhere between drop shots and approach and volleys. When creating an attack and forcing the opponent out of position, it is important to note that there are three ways to take advantage of the opponent’s position and short balls as shown in Figure 5. As just mentioned, angles can be played. The other two are the 2) drop shot and the 3) approach and volley. All rely on pressuring an opponent by forcing them into a poor court position. For example, an angle is highly effective when complemented with a down-the-line in the opposite direction. Drop shots are highly effective when a deep shot forces the opponent well behind the baseline but also slightly wide. These two tactics are deep-short combinations that make the court bigger. The modern approach shot is often the inside-out forehand to the opponent’s backhand, which opens up the court. Two Switches The pace of the rallies on the ATP tour is extremely quick and requires quick reaction, foot speed, and the ability to hit quality shots. Rarely are any of the baseline rallies at the top ten ATP ranking level defensive. It used to be said Federer was the fastest from defense to offense. Instead most rallies are neutral to offense. The modern lighter racquets with polyester strings and sometimes smaller grips allow faster racquet head speed on what was formerly a more defensive shot. Consequently ATP pros are able to play neutral immediately rather than defend. We can describe modern tactics as having two mentalities or two switches. Because of the speed of the modern game, simply calling them phases doesn’t convey how quickly the decisions or tactical momentum change. First, the offensive switch involves attacking by moving the opponent around. The primary method of forcing the opponent to move is the forehand. The second switch is neutralizing the opponent whenever one cannot attack. The neutralizing shot is often to the opponent’s backhand. In addition, today, it is a more common tactic to keep the opponent on the run, hitting to the weaker side as opposed to hitting crosscourt into the opponent’s strength. Djokovic — Federer Case Study Point In the following video, we see Novak Djokovic and Roger Federer play one point in a 26-shot rally that summarizes the tactical points made in this article.

After the serve and slice return to the ad court, a crosscourt exchange in the ad court is made with all backhands save Nole’s inside-out forehand. Nole changes directions with the down-the-line but Federer quickly neutralizes with a high forehand loop back down-the-line. These first six shots (after the initial serve and return) represent a neutral rally where Federer tries to keep the ball in the ad court. A couple shots later, the ball is moved to the deuce court where only two forehand crosscourts are exchanged before Nole changes directions and goes down-the-line. Federer goes back to the ad court initializes another neutral rally of six shots (with two backhand slices). A couple changes of directions occur before Nole is caught and plays a backhand with no change of direction short to Roger’s forehand. The critical mistake was Djokovic’s short ball (without changing direction) to Federer’s forehand. It was the only time in the rally that Djokovic allowed Federer to hit two consecutive forehands, much less not move him. Roger’s first forehand was extra deep which forced Djokovic to go short but Nole did not move Roger from the forehand. Often anything short to the forehand is of course fatal. Roger then plays the forehand drop shot which opens the court with a winning backhand volley deep (deep-short-deep combination). There was one 4-shot and one 6-shot exchange in the ad court without changing direction. Of seven forehands played, four involved changing direction (57%). Of the 14 backhands played, 9 involved no change of direction (64%). Hence, most of the forehands hit were used to attack or change directions and most of the backhands were used to maintain the rally.

Closing Lessons In the US on hard courts, players are often taught to play directionals. That concept includes playing crosscourts as the safer shot unless the change of direction or down-the-line is favorable. Spanish players develop on clay courts and are taught to hit to the open court, changing directions frequently. When changing directions, it is widely accepted that errors will increase but also, the likelihood of winning the rally may also increase due to the opponent moving and the weakness being exploited. Playing safe does not necessarily increase the chances of winning as risk analysis shows (e.g, see the WTA analysis on TennisOne). A player, however, must also acknowledge whether he or she is good enough to play with reasonable margins of errors. Or perhaps we shouldn’t call it margins of errors, but margins for success. Regardless, the crosscourt backhand ad court rally still remains a mainstay in neutral baseline tactics. Among players of lesser skill and weaker forehands, the neutral percentage play can be still be effective for the crosscourt forehand deuce court rally. With the forehand weapon among higher skilled players, it is worth considering ATP tactics. With the concept of hitting to the open court or attacking with the forehand, the ATP pros follow what we can call an anti-directional approach to the forehand weapon. But in applying pressure, the ATP pros understand their margin for success and nonetheless play within their limits. To summarize, one can consider several lessons from the ATP pros:

Remember the modern game is extremely fast, it is essentially a first strike game. If you can play it, go for it, …but don’t blink!

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng

In addition, Doug has written over 70 tennis articles and has been translated into several languages. He consults in mental and physical training and researches in technical and tactical analysis. He has received many awards including most recently the 2012 US Olympic Committee Doc Counsilman Award for his work in tennis. Doug is a member of HEAD/Penn National Speakers Bureau. |