|

TennisOne Lessons Intuition and the World-Class Player Doug Eng Champions like Roger Federer, Martina Hingis and John McEnroe make tennis look so easy! They move effortlessly, anticipate almost every opponent’s move, and make brilliant plays at the right time. They have such amazing physical and mental talents! These players seem to intuitvely be in the right place and select the right shots most of the time. One of psychology’s recent hot topics is intuition. It has been previously looked upon as an old wives' tale or pseudo-science (like ESP) due to the difficulty of quantifying it. But with recent advances in brain research, we are beginning to understand how experts think and expertise is developed. In some fields, such as medicine or chess, expert thinking has been surpassed by computers. These fields have discrete rules and patterns that a computer can recognize and analyze. But other fields -- such as art, music, or sports -- have many variables that are less quantifiable, making it more difficult for a computer to surpass a human being. Tennis is one such sport where intuition can out maneuver in-depth analysis.

Let’s define expert intuition as a spontaneous feeling or impulse to take an immediate and unplanned action, which proves to be the most beneficial action to take in order to positively influence an unknown future event. Tough to swallow? Let’s call it an educated guess or a hunch since we cannot easily describe how we made the decision. It is a gut feeling that we are doing something right. Expert intuition is not to be confused with untrained intuition. Vic Braden in Malcolm Gladwell’s book Blink mentioned he could tell when a player would double fault before the second serve and was probably 100% correct. Braden’s years of experience gave him inner knowledge which admittedly he could not articulate. Recent research suggests that experts from different fields think similarly. Experts use experience to automatically make correct decisions in complex situations. Take the example of one of the Bryan brothers. Bob Bryan has to sense the position of the other players, read his opponents, watch the ball, weigh his tactical options, recognize an opponent's weaknesses, and then physically execute his shot. All this might happen in a split second. A beginner, on the other hand, might not know what to look for or how to proceed if he did. An intermediate player might be overly focused on his or her technique or on watching the ball, not read the opponent's positioning.

Ask Roger Federer how he made a certain shot and he most probably would be unable to articulate his execution or decision-making. Intuition happens all too fast. A beginner needs to verbally and cognitively break down each cue. A beginner may think “split, step left, check my grip, make my turn, watch the ball meet my strings.” A beginner won’t easily pick up external cues nor be able to use relevant information. Not surprising, researchers have shown that beginners and experts actually use different parts of the brain to think. Tennis has been compared to chess. Research shows that chess players think in terms of information “chunking.” For a chess player, an organized group of several pieces on the board has meaning. The world-class tennis player also uses “chunking” to make sense of several things: the opponent’s cues and position, how the court is opening, the offensive or defensive nature of the point, the correct technique, and correct tactical play. Therefore, a certain shot sequence and opponent position has meaning for the world-class player. He or she is able to “chunk” important information. Malcolm Gladwell, the author of Blink, calls this “thin-slicing.” For the world-class player, it is a combination of:

Supposedly, it takes about ten years to develop expertise in any field, including tennis. We see someone pick up tennis at age eight and become a professional player at eighteen. Even if you pick up tennis at age thirty, you may not reach your peak until you are forty. Of course, it depends on how motivated you are. Some researchers think there may be shortcuts to developing expertise. I think there may be short cuts to developing intuition as well. What are the characteristics of intuition on the court? First, it must be spontaneous and effortless. It can not interfere with the mechanics of your strokes. Someone who thinks too much about tactics cannot play effortlessly. Second, intuition, in tennis, demands speed of decision-making. Intuition occurs within a half-second or less; you need to make instant decisions when playing a reaction volley. Third, it involves the reduction of several variables into one simple decision. Tennis, unlike running, is a complex sport as it involves many environmental variables. Last, you need to make the correct decisions. In more measurable fields such as medicine, expert intuition has been shown to be less accurate. Physicians sometimes make incorrect diagnosis but with the aid of a computer they can enhance their rate they make successful decisions. Experts spend less time solving problems, require fewer steps, and are more accurate than novices. Novices tend to cognitively analyze and calculate while experts tend to guess correctly. But it does take experience to develop expert thinking. Intuition is thinking from experience as opposed to thinking by analysis. Experts “thin-slice” and become more efficient using fewer but more highly relevant cues. Learning to read an opponent's cues means studying and reducing them to simple rules. These highly relevant cues include the tossing arm on the serve or the elbow and forearm position relative to the ball. By focusing on a few correct cues, you can anticipate your opponent’s shots quickly and accurately. Because strokes can vary significantly, cues may vary from player to player. That is why even Roger Federer has difficulty against the likes of the magician, Fabrice Santoro. The fFollowing are important things that will help your intuition flow. It takes a while to develop expert intuition but it doesn't have to take ten years (we are trying to take a short cut here!). Practice one concept for a few practice sessions on the court before moving on to the next. Anticipate Offensive or Defensive Nature of the Point Reading the defensive or offensive nature of the point occurs well before the split-step. After you strike the ball, you should already know your opponent’s ability to attack or defend. In fact, since you know what shot you will hit, you should be able to partially anticipate what your opponent can possibly do even before you hit the ball!

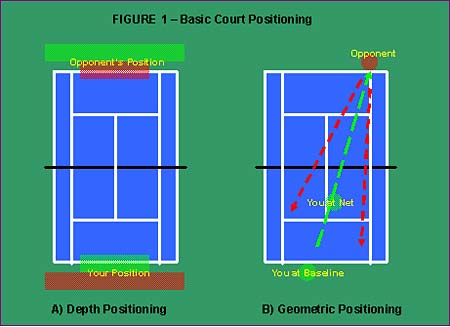

For example, if you can get behind the ball properly and unleash a huge forehand deep into the court away from your opponent, your opponent will most likely need to play a defensive shot. You should immediately take a couple steps inside the baseline. If you hit the ball a bit short and high, you often know before you hit it. So move back slightly a few feet behind the baseline if you know your opponent can hit the big shot. In general, consider your and your opponent’s options relative to the baseline. Of course, against the extreme player -- pusher or the super-hard hitter -- you might weigh your options slightly differently. In Figure 1A, if your opponent is inside the baseline (red), position yourself a few feet behind the baseline (in red, unless he or she has a propensity to drop the ball). If your opponent is several feet behind the baseline (green), position yourself aggressively on or even inside the baseline (green). Of course, if your opponent hits very deep, you will have to move back. The purpose, however, is to partially anticipate for the likelihood of a shorter ball. Zone Call Drill

In the Zone Call Drill, have a friend feed you balls and try recognizing the flight of the ball and guess where the ball will bounce as fast as you can. Quickly indicate your guess by raising one, two, or three fingers and see if you guess correctly. The calls are out, one (if the ball is four feet within the baseline), two (if the ball is between 4 and 15 feet of the baseline, and three (if the ball is within three feet of the service line or shorter). Or quickly move into the zone (1, 2 or 3) where you think the ball will bounce before the ball actually gets there. This drill forces you to make faster decisions. You can replace one with defend, two with neutral, three with attack. You may also vary the zones since different players can attack off different heights and depths. The second video shows a drill where a friend feeds you balls and you practice moving in if your ball does one of two things:

As in the video, you may want to mark off a line 4-6 feet from the baseline as the attacking zone. As an option, you can add the rule if you hit short, you recover a few feet behind the baseline to anticipate defense (call “back!” or “defend!”). For every ball your opponent hits, there are two extreme directions. From the sidelines, your opponent has the down-the-line and the crosscourt. Get into the optimal position that covers both shots as shown in Figure 1B (above). Once you get into a position that covers both options, you will need to then consider: a) your opponent’s favorite tactics and b) your best shot. You may then try to take a small step in the direction that helps you cover your opponent’s favorite tactic and that gives you a good chance to play your big shot.

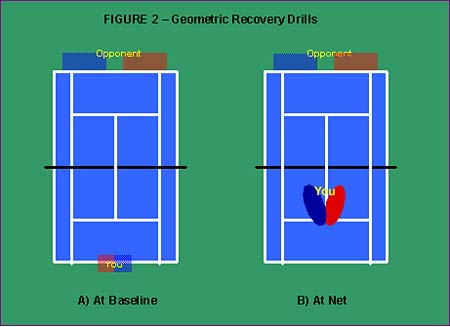

For example, if you know your opponent likes to hit to your backhand and you have a big forehand, recover to the geometric position and then take a shuffle-step towards your backhand. Don’t take too big of a step since your opponent will then hit wide to your forehand. Eventually, think of recovering slightly off the geometric center to cover your and your opponent’s best shots. Steffi Graf would always move a bit to her backhand to open the court for her big forehand. Groundstroke Geometric Recovery Drill Practice rallying with a friend with both of you at the baseline. Keep the ball in play and practice hitting crosscourt and down-the-line and recovering slightly to the opposite half (about 2-3 feet away from the center). If you hit a great angle, recover a bit more wide ( e.g., 5-7 feet away from the center). In Figure 2A, if you hit to the big red target, recover to the small red target. If you hit to the big blue target, recover to the small blue target. Net Geometric Recovery Drill Practice rallying with you at the net and your friend at the baseline. Start just inside the baseline and feed a ball and practice moving in as if it was an approach shot. Recover slightly on the same side as your volley or approach shot. If you hit a straight volley, you should stay on that side (1-3 feet off the center line depending on the placement). If you hit a crosscourt approach or volley, make sure you cross the center line over to the same side as the approach or volley. Avoid a couple mistakes many intermediate players make: a) moving to the center line after the approach or volley (only do so if you play the ball up the middle) and b) forgetting to cover the crosscourt volleys. In Figure 2B, if you hit to the big red target, recover to the small red target. If you hit to the big blue target, recover to the small blue target. The purpose of the split-step is to assist you in exploding towards the ball. Just before you split-step, you read your opponent’s backswing and proximity to the ball. Get in the habit of timing your split-step almost at the same time as the contact point. But intuition involves more than timing the split-step, it involves reading the play as you split-step and immediate movement in the right direction. Many players land too statically when they split-step and lose any momentum to go anywhere. Keep in mind, it is a split-and-spring into action movement. Don’t split-step and stop your momentum.

Some players split or make the first step after the split too wide which stops their momentum. Keep in mind that a smaller split-step going to the net might make you less stable but quicker to push and spring into action to go forward left or forward right. At the baseline, you may take a wider split-step since you tend to go either left or right (not forward). If you think your opponent has a chance of hitting shorter, use a narrower split-step. There are narrower variations on initial movement which includes the gravity step and flow step going towards the net. I won’t go into details here since there is a great deal of information you can look up on the split-step and initial movement. Sit and Split Drill There are two parts for this simple drill.

Speed-Read Opponent Cues It has been shown that experts don’t have faster reaction times than the average person. Rather, they know sport-specific cues and can read and anticipate what might happen next. So if you think you are slow at reacting in highway traffic and hitting the brake, you can still have near world-class anticipation if you train. Some researchers believe that world-class tennis players and other athletes may have superior innate intelligence for smoothly automating their movement skills. So even if you have world-class intuition, you might still have a jerky stroke. That is why we see some very good tennis players who look awkward and slow but always seem to get to the right place and make solid contact. As we mentioned earlier, some players are harder to read since they have unorthodox technique or they are creative with great variety. That is why Federer has trouble playing against Fabrice Santoro. But you can read most players by following some simple rules.

According to research, the single most important last-second cue is the opponent’s forearm, elbow, and racquet position before contact. Pros will read their opponents very quickly and accurately from this cue group. In addition, you should also read cues from your opponent’s ability to recover. If your opponent is off balance longer than usual or slow to recover, hit to the open court. If your opponent recovers quickly but is still moving and not ready to split, hit behind your opponent (or back to the same spot). Here are some ways to practice speed-reading your opponent’s cues. Try printing the seven forehand photos below as four inch cards or photos. Quickly have a friend flash a card and you guess the possible strokes and offensive or defensive nature (e.g., ‘big forehand, defend” or “lob, prepare for an overhead”). Note court position, balance, stances, and racquet face and arm positions. Note there are no captions! You need to figure out the shot possibilities. Do for speed. You can also make your own cards. Spin and Volley Video three shows what I call the Spin and Volley Drill. Stand with your back to the net. Have a friend be a feeder and have him or her stand in either the deuce or ad court. You should not know where the feeder is. The feeder calls turn and feeds the ball at the same the time. You quickly spin around and make a reaction volley to the open court. To make it easier, have the feeder stand at the baseline. A more advanced version is having feeder stand at the service line so the balls come at you faster. This drill forces you to quickly read and volley to the open court.

Conclusion In summary, to develop intuition on the court you need increase your expert knowledge of the game particularly in court positioning and reading opponent cues. This process will take some time and thinking. At some point it will become more automatic. You also need to practice for speed without analysis. Do exercises that speed up your ability to process information such as the Turn and Volley Drill. Many players don’t do these types of drills. Intuition’s cousin is creativity. The more shots and tactics you have, the more creative and intuitive you can be. Without great execution, you can’t take advantage of your intuition. Practice enough so that not only are your strokes more automatic but your tactics become automatic also. There are different tactics for every level. It will take diligence and lots of repetitive plays to hone your skills. But at every level, you can become a better intuitive player and play a little more like Roger Federer. Have fun! Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |