|

TennisOne Lessons Comparative Analysis of the Open-Stance Two-Handed Backhand: Doug Eng EdD, PhD The modern two-handed backhand is arguably the most varied stroke in terms of grips, arm position, body movement, and stances. An important variation is the open-stance backhand which we shall examine here.

You might hear that the two-handed backhand is like a forehand with your non-dominant hand. There is a bit of truth to this but not quite. Unlike the forehand, the two-handed backhand is not often hit from an open-stance. Many players find it more comfortable to hit the backhand from a square or closed stance. It has, however, been debated that the open-stance backhand should be used almost as much as the open-stance forehand as it facilitates recovery. Pushing off the left foot (for a right-handed player) from an open stance helps turn the hips back into the court. Many service returns are hit from an open stance as there isn’t enough time to adjust the feet. A square or closed stance requires at least one extra step and often a pause between the hitting phase and footwork recovery phase. Whatever the advantages they get, touring pros favor the open-stance less than the square or closed stance. So you might ask why it is not favored? When would they use it? Let’s answer these questions. Then let’s comparing the strokes of Rafael Nadal, Martina Hingis and Mardy Fish. Although Hingis has once again retired, her backhand is worth studying as she is regarded as one of the most technically sound players and she frequently employs the open stance. Mardy Fish is an interesting study in light of his recent results at Indian Wells where he reached the finals en route defeating Federer. (Please note in the following article that all references are to the right-handed player) When to Use the Open-Stance Two-Handed Backhand The open-stance two-handed backhand is best used:

The open-stance backhand is used especially on the first serve return when you lack time to turn quickly. In addition, the open stance limits the length of backswing you can take; if you turn sideways, you will use a longer backswing. From the ad court, the open stance also naturally sets your body to hit the return crosscourt back to the server, the easiest direction. In addition, double-handers at the baseline hit open-stance groundstrokes on moderately wide balls near the sideline. The open stance on wide balls facilitates recovery back to the center of the court. The outside foot (the left foot for a right-handed player) closer to the sideline provides braking, loading, and recovery as we will soon see. As in the service return, the body is naturally turned to hit crosscourt. Comparison with the Open-Stance Forehand The two-handed backhand has been often compared to a forehand hit with the non-dominant hand. If that is true, why is the open stance less preferred on the backhand than the forehand? There are several reasons:

First the grips for the forehand and the two-handed backhand are different. Depending on the grip of the dominant hand on the backhand, the right or left hand or both hands may control the swing. If you use an eastern backhand grip with the right hand, your right hand dominates the swing and the left hand merely stabilizes the racquet at contact. For example, former great Jim Courier used an eastern backhand grip with his dominant right hand. If you use a continental grip with the right hand, either hand can control the swing. Andy Roddick and Andre Agassi use a continental grip with the right hand. In Roddick's case, the left hand controls the swing as his right elbow is bent but the left arm is straight during his swing. He cannot use his bent right arm for power, but merely support. The best indicators of a weaker arm are a bent elbow and a broken wrist (as many players often break the wrist in the dominant right hand). Agassi, however, straightens his right arm away from his body and has gone on record stating his right arm dominates the swing. In another style, Monica Seles hit her backhand like a forehand as her dominant (left) arm was bent and close to her body. But not every two-handed backhand is like a left-handed forehand. On the forehand, if you are right handed, you load on the right foot; you put weight on your dominant, stronger leg. On the backhand, many players find it harder and more awkward to push off the left non-dominant foot. Instead it is easier to step in on the dominant right foot which squares off or closes the stance. The backswing on the forehand naturally extends away from the body more than the backswing on the two-handed backhand. Extension of your arm on the forehand backswing allows greater weight shift to the back foot. The loading on the back or right foot shifts the center of gravity close to this foot. The left or front foot frequently comes off the ground to keep balance. We see the loading and balance on the forehand in Photo 1 with Martina Hingis on the left. The green arrow indicates that her weight is on the back foot. The yellow line indicates Martina’s head position and perceived center of gravity. In the middle image in Photo 1, we see that the left arm counterbalances the backswing and assists in the shoulder turn. Even on the follow-through, weight frequently does not shift to the left foot which can lift off the ground. If the left foot is allowed to lift and swing back, the hips easily turn back towards the center of the court. In addition, the shoulders turn more for greater angular momentum. Sometimes as a natural consequence of angular momentum, players spin both legs -- as Justine Henin is doing in photo 1 -- to facilitate recovery. Even in mid-air, Justine’s head position and center of gravity remains closer to the right foot than the left foot.

In comparison, on the open-stance two-handed backhand, the backswing is more compact because both hands still hold the racquet. The compact backswing does not shift the center of gravity backwards but allows a more even balance. One might argue that because both hands are back, the player might shift weight to the back or left foot. This weight shift, however, rarely happens except in very wide balls. In Photo 2, we can see that Donald Young is very balanced (see yellow line) even though he still loads on the outside (right) foot. On the follow through, Victoria Azarenka (Photo 2) has shifted her weight to the right foot. The weight shift from one foot to the other occurs more frequently on the backhand rather than the forehand which can involve a spin move that swings the left foot back.

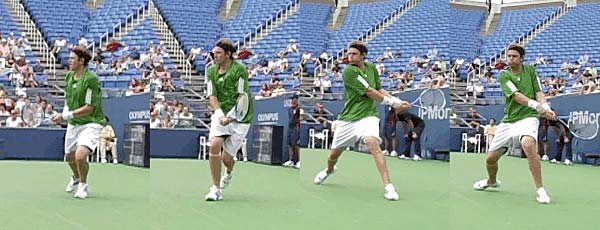

Finally, the two-handed backhand rarely involves feet coming off the ground as in the forehand. The backhand is more grounded as the left leg does not load as powerfully and the center of gravity is more evenly maintained than in the forehand. Most players prefer a simple foot to foot weight shift. Therefore a spin move where both feet leave the ground rarely occurs on the backhand. Movement to the Ball Let’s look at our three professional subjects now. Photo 3 shows Fish, Hingis and Nadal in the pre-contact phase of the swing. The first set of frames shows the initial step out towards the backhand. Weight comes off the inside (i.e., closer to the center of the court) foot and the outside foot turns towards the sideline. The racquet does not come back yet as some people think but remains in front. The second set of frames show the crossover step. Note Hingis likes to keep her racquet in front a bit longer. Her racquet head is still up. Nadal has taken the racquet slightly back but with the racquet head cocked upwards. Rafael’s racquet head is well above his hands. Fish likes a lower non-cocked racquet head where the racquet head is marginally above the hands. In the third set of frames in Photo 3 (A through C), we see all three pros firmly plant the outside foot in extremely wide, powerful stances. The inside foot is off the ground and moving to narrow the stance. The wide stance and racquet preparation creates a large separation angle between the hips and shoulders. The shoulders coil as the racquet is pulled into the full backswing. You can see and almost feel the power emanating from Nadal’s coil.

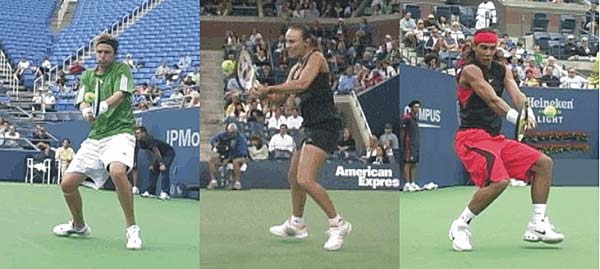

The last frames on the right shows each pro in the low point of the swing as the racquet now swings forward. The outside leg has fully braked and now flexes to provide power into the swing. Fish has the flattest swing plane. Nadal drops his racquet head the lowest as he will hit with the most topspin. His swing is like the C motion swing you might use on the forehand. For all players, the inside or dominant foot has moved closer to the center of gravity. That narrows the stance as the translational momentum shifts sideways along the baseline to push off and recover in the next (post-contact) sequence of photos. That is, the players were moving out to the sideline but will start moving back to the center. Contact Point In Photo 4 we essentially see the contact point (or close to the contact point) of our pros. Hingis and Nadal just made contact so their racquets are a bit more in front of the body unlike Fish who is right at contact. You can see that Nadal’s and Fish’s front arm are considerably straighter than Hingis who has both arms bent. In fact, most female touring pros tend to bend the elbow and brace their elbows against the body more than their male counterparts.

Movement after Contact In the next set of photos (5A to 5C), look for three major motions. The first is the follow-through of the racquet through to the target with the arms straightening and then wrapping around the shoulder. The second is the push-off weight transfer from the outside loaded foot to the inside foot. This motion usually occurs in synchronicity with the follow-through, although as we see in Nadal’s case, he has completed his follow-through still on the right foot. If the force is great enough on the outside braking foot, the follow-through may occur as the center of gravity is still moving away from the center of the court. The third motion is the turning of the hips towards the center of the court which allows for a quick recovery. Note in the third images, maximal follow-through is shown as the racquets for all three pros come over the shoulder or back. Nadal has the most extreme back wrap as his elbows go up high. Hingis actually keeps her right elbow a bit lower which keeps the racquet from coming down on the back. When you see a more compact follow-through that just comes over the shoulder, you will note the right elbow often tucks low and close to the torso rather than at shoulder height. Although the follow-through is completed, the weight is still on the outside foot. None of the players have yet shifted weight to the inside foot. However, braking is complete and the player will begin to step on the inside foot back to the center of the court. The last set of images on the right show each pro already pushing back into the court. Note the racquet is no longer over the back but in front to better facilitate balance, recovery, and readiness.

Practice There are several important elements to practice on the open-stance two-handed backhand. The first is the movement towards the ball. Rather than trying to just shuffle step along the baseline, split, pivot, and use the crossover step to accelerate sideways towards the ball. Second, on your last step before contact, practice moving forcefully and stepping out wide with the left foot to create a braking action. I find players better develop loading from an open stance when they are forced to move quickly and step wide; it is very hard to artificially create off slow steps (similarly like trying to slide on clay without any initial acceleration). So practice moving fairly quickly to an imaginary ball. Then practice stepping wide to a fed ball.

Loading on the non-dominant leg takes practice. Try letting your left leg bend as weight is put on that leg. Think of putting both hands down on the backswing near the left thigh and push down. In a drill, start with both feet on the baseline as someone feeds you balls. You will find yourself turning the shoulders and torso rather than trying to set the feet sideways. In addition, practice the recovery phase. Whatever your racquet swing path, follow-through over the shoulder to help turn the hips and shoulders back to the center of the court. Your left shoulder should come forward and your belly button should face back towards the center of the court. Last, feel the outside foot push off as weight moves to the inside foot. You may want to practice putting your feet on the baseline and swinging without the ball, shifting your weight from the left to the right foot (assuming you are right-handed). In summary, try using the open-stance on your two-handed backhand on the service return and on moderately wide balls. You will find yourself recovering more quicker and moving more efficiently. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Bobby Bernstein and Paul Lubbers of the USTA Player Development in Key Biscayne, Florida for the use of their video clips which were converted into photos via Dartfish software. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |