|

TennisOne Lessons Payoffs: Groundstrokes and Directionals A comparison of Justine Henin-Hardenne and Maria Sharapova Doug Eng EdD, PhD General Statistics and Introduction to Payoffs Traditional tennis statistics can summarize a tennis match but are lacking in helping players to understand the success of specific tactics. Merely counting the number of unforced errors on the backhand doesn’t tell us which was better: the crosscourt or down-the-line. Many recent graphical statistics don’t illustrate the success of particular shots or tactics. For example, graphics might show the placement of the second serve but not the effectiveness of down-the-line passing shots against an inside-out approach shot. More important than counting winners and unforced errors, are the actual probability and frequency of a shot or tactic. In game theory, mathematicians address winning or losing scenarios and their probabilities. For example, in blackjack or 21, we know the approximate odds of winning if we hit on an 11 or a 17. Depending on what cards are still available in the dealer’s deck, the probability will have some variance. The chance of winning, adjusted for betting, is called “payoff.”

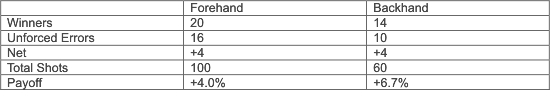

When you buy a lottery ticket, you might also understand the odds and the jackpot total which can be used to calculate your payoff. In sports, we see payoff calculations in football such as conversion of third or fourth downs. In baseball, a simple payoff calculation might be batting average or average at-bats per home run. A more sophisticated payoff recently used is the hitting grid of which an example is shown in Figure 1. Assume we have the pitcher’s view and the batter is right-handed (and on the right). This hitter is weak on high pitches and stronger on away and low pitches. The deep blue shows the weakest locations. The strong red means the hitter is hot in that location. A pitcher’s best location would be high and inside near the hitter. Unfortunately this statistic is not particularly useful in tennis. If we make a grid of where a tennis player hits successfully relative to the body, it would vary depending on the grip but also the placement on the court. In addition, a tennis player may choose to move and take the ball higher or lower, which a batter cannot do. There are other statistics we can use, however, that are not used currently. First let’s define the payoff of a tennis shot as: % P i = 100 (W i – U i) / N i where i=particular stroke technique, W=winners, U=unforced errors, N=total number of (i) played. Let’s say you hit 30 overheads with 5 unforced errors and 15 winners. You might win another 8 points after a few more shots (e.g., volleys), but the 15 represents the total outright winners. Your payoff for the overhead is = 100 x (15-5) / 30 = +33%. On the other hand, the lob is a defensive shot and you might hit 24 lobs in a match with 8 errors and 4 winners. Note we are just looking at your lob only, not your opponent’s ability to hit a winning overhead off your lob. Your payoff will be = 100 x (8-4) / 24 = -16.7%. Basically, that means for every 3 overheads you hit, you have a net gain of +1 point. And for every 6 lobs you hit, you lose a net of -1 point. It is true that the overhead and lob might also set up other shots, but let’s just examine the direct effects for now. What is an advantage of payoffs over traditional statistics? Let’s look at some traditional statistics for player in Table 1. Table 1: Sample Winners and Unforced Errors

Using the above chart, one might guess that the forehand and backhand were about the same. But let’s look at more data shown in Table 2. Table 2: Sample Payoff Difference

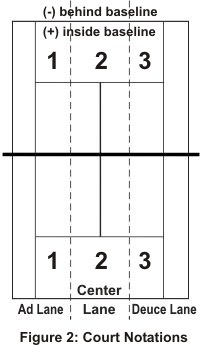

This player made the choice to run around the backhand (hitting 100 forehands and only 60 backhands) thinking the forehand is a bigger shot, but we can see that the +6.7% payoff on the backhand is superior to the 4.0% forehand payoff. Therefore, we can see that traditional statistics can be misleading and incomplete. If you were this player knowing this data, what would you adjust in your game? In the Figure 2, let’s say you are the player at the bottom of the court. The ad court lane is referred to as “1,” the center lane is “2,” and the deuce court is “3.” Let’s introduce two other parameters “-“ referring to a shot hit from behind the baseline and “+” referring to a shot hit in front of the baseline. Let’s say your opponent is standing in the ad court lane (1) and strikes a forehand crosscourt that travels to your deuce court (3). You are standing inside the baseline (+) and decide to aggressively hit a forehand down the line (3). Your shot may then be called a 133f+, meaning you stood inside the baseline and took your opponent’s crosscourt to hit down the line. Let’s look at another example: 313f- means your opponent (if right-handed) struck (from 3) a backhand crosscourt to your ad court (1), and you choose to run around your backhand to played an inside-out forehand to your opponent’s ad court (3) from behind the baseline (-). Let’s look at one more description: 113b+w means you took your opponent’s down-the-line forehand from the deuce court (1), stepped inside the baseline (+) to hit a winning backhand crosscourt to the ad court (3). The last symbol w means winner. In addition, u=unforced error and f=forced error (if you missed because your opponent hit a great shot). We could also look at spin, depth, pace, and height of the ball as additional parameters but adding more parameters might also make data collection and grouping more difficult. In addition, the 3 lanes are a simplification in order to collect meaningful data. Comparison of Justine Henin-Hardenne and Maria Sharapova If we combine this type of charting for groundstrokes with the definition of payoff, we can uncover some patterns that baseliners play. Let’s take the examples of Justine Henin-Hardenne and Maria Sharapova. I picked these two female baseliners since they have contrasting styles. Maria is a first-strike dictator of play with the common but terrific two-handed backhand. Justine is an athletic all-court player with an atypical one-handed backhand.

We hear that Maria was coached to take the ball early and to hit fairly flat and aggressive. Justine made her run to the top in the last three years by training very hard and improving her mental toughness. Maria won Wimbledon with her big game and Justine won Roland Garros and the two hardcourt Grand Slam events with her movement and all-court ability. Justine (and Mary Carillo) also indicate that her rise to #1 was strongly due to her forehand now considered her weapon rather than her famous backhand. We see in Table 3 a summary of the two women on hardcourts. It is simple to see that Maria is far more consistent on the backhand partly because she will go for bigger shots on the forehand. About ¼ of Maria’s forehands are hit for outright winners! But her actual payoff is only 10.7% inside the baseline and in contrast -8.9% from behind the baseline. So although Maria hits 26% winners on her forehand from inside the baseline, she can only win a net of +1 point for every 10 forehands played (10.7% payoff) Maria's backhand is more reliable from behind the baseline but less of a weapon inside the baseline. Justine, on the other hand, just hits better on her backhand from behind or inside the baseline. She has a terrific payoff of +9.7% inside the baseline on the backhand.

In Table 3, we see an advantage of payoff over just counting winners and unforced errors. Payoff is a statistic that combines the two other statistics with frequency. We also see that from behind the baseline, it is difficult to win a match as typical payoffs are -4 to -9%. Not surprising. Positive payoffs occur inside the baseline. Can a positive payoff exist from behind the baseline? Yes, as we will see in Part II, but they are exceedingly rare. So don’t expect to win many matches hanging behind the baseline but instead develop ways to attack the short ball as your teaching pro might say. For the remainder of this article, let’s focus on backhands or the ad court lane only. In Part II, we will examine their forehands from the middle of the baseline and from the deuce court lane. Justine Henin-Hardenne

Let’s first examine Justine’s backhand off the crosscourt. We already saw an overall picture which shows Justine’s backhand is more effective than her forehand, although she may believe otherwise. Keep in mind that time can be a factor. For example, a player may work on her volleys which become better with time. This study did look at a range of matches from 2003-2005 when she was at her best. We need a variety of matches (and opponents) and large number (>1000) of shots to come up with reasonable data to show overall tendencies and not particular tactics in one match or against one type of opponent. In Figure 3, we see that Justine has an amazing backhand from inside the baseline. She has a payoff of +31.6% meaning she has a net gain of an outright point for every three backhands she hits! Justine’s lowest payoff is when she plays to the center. Relatively low payoffs should occur in the middle of the court since those shots don’t force opponents to run. Her -14.3% payoff from inside the baseline is higher than her -7.9% behind the baseline. This discrepancy is probably due to infrequency of the shot (10.6% frequency) and probable mishits and difficult balls. When we look at Justine from behind the baseline, we see less success as expected. Her down-the-line was -32.4% from behind the baseline and +31.6% inside the baseline – a very extraordinary difference! She probable understands this very well since she is nearly twice as likely to hit down-the-line on a short ball than if behind the baseline (28.8% vs 15.4%). In fact, behind the baseline, Justine is more nearly three times more likely to play to the middle of the court (28.5% compared to 10.6%). In roughly 60% of her responses, Justine plays percentage tennis and does not change the direction of the ball, preferring to play the crosscourt. Her response is a good example of what you might be taught: work the ball mostly crosscourt and attack the short ball by going down-the-line. How can Justine improve her shot selection? She might want to go a bit more frequently down-the-line on short balls (e.g., 40-50%) as that is her most effective shot (more effective than any type of forehand she hits).

Justine hits a very good backhand, but what happens if she runs around and hits a forehand? In between the courts in Figure 3 is data for the forehand (inside parentheses) from the ad court lane, both inside and behind the baseline. Inside the baseline, Justine’s forehand is very comparable to her backhand, in fact almost the same numbers. For example, her inside-out forehand has a payoff of +14.3% compared to her backhand of +12.5%). But her forehand from behind the baseline is, in fact, superior to her backhand! For example, her inside-out forehand has a payoff of +8.0% but her backhand is only -7.3%. In fact, that +8.0% payoff from behind the baseline is quite high.

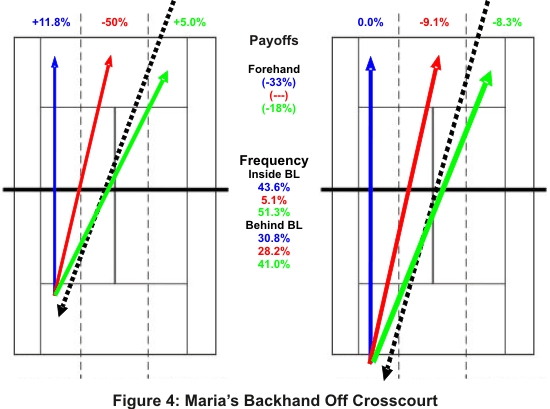

In short, Justine has a terrific backhand inside the baseline, but if she has time in a deep situation, she should run around it to hit the forehand. Not surprisingly, Justine will play many neutralizing balls to the middle when she is in a defensive position on the backhand side. Maria Sharapova Maria’s backhand results off the crosscourt are shown in Figure 4. Her numbers are a bit similar to Justine. Inside the baseline, Maria’s best shot is the down-the-line with an +11.8% payoff. It seems, however, she is a bit smarter than Justine in taking advantage of this shot as she tried it 43.6% of the time (compared to Justine’s conservative 28.8%). Maria’s crosscourt also had a lower payoff than Justine. In short, Maria is not as strong as Justine on the backhand inside the baseline. Maria was also slightly less effective than Justine in going crosscourt from behind the baseline (-8.3% compared to Justine’s -7.3%). But she smartly plays her down-the-line from behind the baseline nearly a third of the time (30.8%) as her payoff is 0.0%. The 0% payoff is actually excellent for a counterattacking shot. So Maria may have a weaker crosscourt, but her overall backhand is quite effective from behind the baseline since she frequently hits the down-the-line, her best shot. Keep in mind that Justine rarely goes down-the-line in that defensive position, which is also smart for her as her shot is quite ineffective.

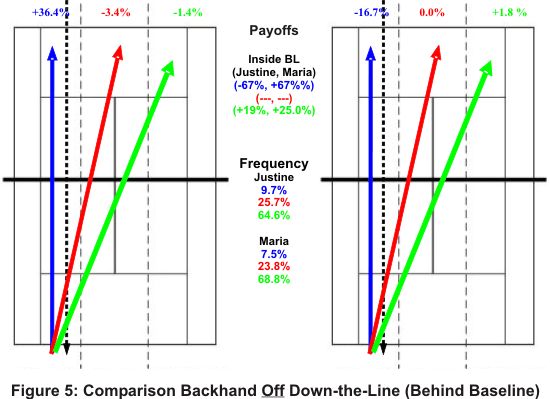

What happens if Maria tries to run around her backhand to hit the forehand? We see the numbers for the forehand (between the court drawings in Figure 4) are not very promising. Unlike Justine who had very good numbers, Maria’s numbers are poor (-33 and -18%). She should not run around or perhaps she should work on her weakness. Most likely some of it is due to her footspeed not being as effective as Justine's or even going for too big of a shot off-balance. Let’s look at shot selection when defending against the down-the-line. Figure 5 summarizes the results for both Justine and Maria. Justine's results are shown in the left court and Maria's results are shown in the right court.

Here we see both players stick to basic percentage tennis in that they both choose to hit about 2/3 crosscourt. Justine was slightly more likely to go down-the-line which was a good choice for her as she had an astonishing +36.4% payoff. Her high payoff is partly in due to 1) the infrequency of the shot so she may have the element of surprise, and 2) she may well be hitting behind the opponent. Maria had slightly better chances going crosscourt. An infrequent scenario was the response inside the baseline off a down-the-line. These results are shown between the court diagrams in Figure 3 (in parentheses). In fact, this happened only 37 times of the over 3,000 shots in this study. This shot combination is rare because the down-the-line is often an attacking shot and players rarely play inside the baseline off it. Good footwork requires you to move back a bit when under pressure. The results need more data but may indicate that both players have very effective crosscourts when they take the ball early (payoffs of 67% and 25%). The lesson here is that their opponents should take extra care not to hit a short down-the-line. Conclusions Justine has a very highly effective backhand inside the baseline. She should consider playing the down-the-line more frequently when stepping inside the baseline as her payoff is a whooping +31.4%. It is true that her payoff may decline if she plays this shot more frequently as she may lose some element of surprise and might not be ideally prepared. On the other hand, behind the baseline, Justine probably should try to run around the backhand more often or play to the middle as her backhand is not as effective. Maria is aggressive in breaking percentage directional patterns off the crosscourt. Inside and behind the baseline, her most effective shot is the down-the-line. She plays the down-the-line almost as frequently as her crosscourt which is a good tactic for her. Opponents must be alert when playing to her backhand as to not overguard against a crosscourt response. We often hear that when you go down-the-line, it is a more difficult shot with more margin for error. Physics and mathematics show that the down-the-line is a more risky shot. But an examination of payoffs with Maria show that physics might not be providing the best answer all the time. It is important to realize that in tennis, the majority of shots are hit crosscourt and therefore, going down-the-line is hitting to the open court. So payoffs will tend to be higher than going crosscourt again. Likewise, if two tennis players exchanged several down-the-lines, the crosscourt would have the high payoff as it is to the open court. Maria has, for example, a payoff of 25% when returning the down-the-line with a crosscourt inside the baseline which is higher than her 11.8% going down-the-line off the crosscourt. When Justine was inside the baseline, she was an astonishing 31.6% going down-the-line off the crosscourt but also, a very good 19% going crosscourt off the down-the-line. When inside the baseline, changing directions will give the highest payoffs. If we could suggest something to Justine, it might be "hit more backhand down-the-lines when inside the baseline."

Maria presents an unsual case with her backhand off the crosscourt from behind the baseline. We saw in Figure 4 that her best shot was down-the-line, not crosscourt. Often, we are taught to go crosscourt from this position. Remember the story that scientists calculated that bumblebees can’t fly? Things aren’t always what they seem not to mention the calculations were incomplete. Perhaps some players fall for coached patterns too regularly and expect Maria to hit the crosscourt which gives her excellent chances on the down-the-line. In addition, her crosscourt also moves opponents off the court a great deal and then perhaps opens the down-the-line more than other players. But this answer is partly satisfactory since Maria plays the down-the-line 30-45% depending on her position. The fact that Maria plays her down-the-line closer to 50% makes her more unpredictable and makes it harder for opponents to cover the baseline (as opposed to someone who hits 80% crosscourt). In any case, her down-the-line was, in this study, her best shot from behind the baseline and will get her good results. Maria will attack frequently from behind the baseline. So, should the recreational player practice the same tactics? Probably not, as the window for error is significantly greater for the club player than Maria.

Sometimes, we use theoretical science to predict what should happen and what we should do. But often, empirical science demonstrates that we should actually look at what happens rather than calculate what physically should happen. We watch technique and learn from it. We don't predict technique. Why not apply observations and payoffs to judge groundstroke tactics rather than just saying this shot is better than that one because the angle is harder to change? Because of the human nature with empirical results, we may see some contradictions from theoretical predictions (as we have seen here). Finally, payoffs will actually change with technical practice and usage habits. There are human components to tactics. A good poker player knows when to bluff and how to win off it.

Next time, we will look at Justine’s and Maria’s forehands from the deuce court and from the middle.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |

Like any other statistic, payoffs won’t tell you the full story, but it can give us a normalized profile (for example, if you hit an equal number of forehands and backhands). Let’s look at more detailed information, combining payoffs with directionals.

Like any other statistic, payoffs won’t tell you the full story, but it can give us a normalized profile (for example, if you hit an equal number of forehands and backhands). Let’s look at more detailed information, combining payoffs with directionals.