|

TennisOne Lessons Hitting the Forehand on the Run Doug Eng EdD, PhD

Stefan Edberg once said, “everyone can hit the ball out there, but getting to it and getting to the right place at the right time is really what tennis is all about. It's really a running sport." Being able to cover the court is important in tennis. Our opponents often try to hit away from us and make life on the court miserable for us. But it’s still fun! If you watched the recent French Open at Roland Garros, you probably marveled at the movement of players like Rafael Nadal. The best tennis players are often those who strike the ball well but also move well to produce show-stopping shots. On the other hand, the typical tennis player often spends too much time trying to figure out what’s wrong with a stroke rather than improving movement. And when we spend time on footwork, it is often on the split step, stance, or recovery. Many players are over-taught stances. Rarely is focus on movement towards the ball. Learning shot-making in tennis involves the whole hitting cycle which has four parts:

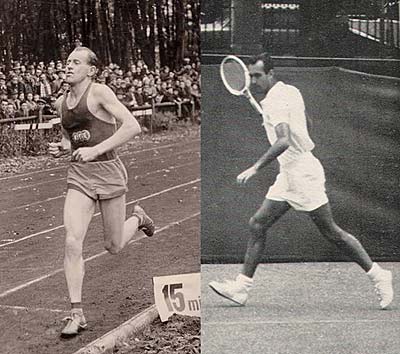

In this article, we will focus on the second phase (movement to the ball), especially under pressure and the last few steps that set up the shot. We will address running situations where the player cannot stop and load. Please note we are addressing hard court situations as this is also possible on clay courts where sliding on the right left is preferred rather than striding on the left leg. Footwork on the run is a natural process. We will also examine hitting on the run at the baseline and on the run towards the net. We will find out that they are basically the same movement pattern although they are often addressed differently. Although I might say hitting on the run is a natural process, we are sometimes over-taught how to move towards the ball. Some players are taught to split and shuffle step for almost everything. Some players jump too high on the split, too early without consideration of recognizing what the ball is doing, or get into artificial stances because they were taught to use that stance. Sometimes, movement becomes so over-trained, it becomes unnatural. Speed, fluidity, and biomechanical efficiency are important considerations in movement. So, let’s try to simplify footwork on the run. Run and Hit On the Baseline When on the run, you will find yourself taking fairly large strides as compared to walking. In fact, that’s how paleontologists estimate the speed of dinosaurs. From fossilized footprints, they create a model of stride length at walking speed and then as the stride length increases, the animal is estimated to move faster. Similarly, if Bill Tilden and Rene Lacoste strolled out on the clay of Roland Garros (as they did in the 1927 finals), we might actually be able to estimate the speed of either player by examining the footprints in the red clay. In a side-by-side photo, we compare a runner (the great Emil Zatopek) with a tennis player (tennis great Andres Gimeno) running to play a forehand. In both cases, the right leg and left arm swing forward together. As the left arm moves forward, the left shoulder also shifts forward with the right leg. The right shoulder and left leg drop back. The arms essentially swing to counterbalance the legs which create angular momentum in the hips and shoulders. The arm swing creates extra momentum and makes movement more efficient. Finally, there is some natural loading off the right foot since the knee naturally flexes as much as 40-50 degrees when running.

On the backswing, some people try to step on the left foot and also throw the left arm forward. That allows the right hand to drop back and create a backswing. It also results in a closed stance well before contact. From there, the racquet swings forward as the right leg pushes forward. This movement is like how a camel runs. A camel almost simultaneously moves the right legs at once and then moves the left legs at once. Unfortunately, this movement is unnatural for humans and is inefficient although at times you might do this since you may lack full control of your body when running. Let’s take a look at a touring pro forced on the full run. First, we look at Maria Sharapova, who isn’t known as the best mover but is no camel either. Maria takes small lateral steps out of the split step before accelerating to large steps as she explodes to the ball. Note the stride length of her last two steps. As she takes a large step with the right foot which opens her stance, her shoulders naturally rotate which promotes her backswing. Her hips are tilted forward as a sprinter might do to assist acceleration. As she creates her backswing, she actually begins to decelerate and the right knee starts to break and flexes about 50 degrees. Therefore, she naturally loads, albeit briefly. Her forward swing occurs simultaneously with her left foot stride which closes her stance. The contact point occurs with an almost square stance (that is, the feet are equal distance from the side line). After she strikes the ball, her stance closes and the stride length decreases significantly as she brakes.

Now understanding Maria’s natural footwork, let’s also look at Roger Federer. Federer’s two biggest strides are 1) as his hands separate, his left foot strides forward and 2) his right foot strides as his racquet is in the full backswing. In the first, his racquet remains in front which makes sense if his left leg moves forward. When his racquet goes back, his right foot is well in front and almost about to land. As he starts his forward swing he only created modest flexion in the knees. Actually he reaches maximal knee flexion (60 degrees) as he reaches contact. That is because he is decelerating to maintain body control. As he makes contact (like Mari), his stance actually squares off. After contact his racquet decelerates and his stride shortens for recovery. Federer’s strides are slightly shorter than Maria (who probably ran harder) and he maintained better body control. After contact, as Federer recovers back into the court, you can see he creates a greater lean back into the court than Maria. Run and Hit the Approach on the Short Ball

Now let’s take a look at what happens on a short ball. Sometimes we take approach shots when we can set up, load, and rip the ball. Then we follow the ball in if our opponent looks to be in trouble. One might call this tactic a crush and rush approach. Other times, we are forced to go to the net by a drop shot or a ball shorter than we expect. Let’s focus on this area: when you are forced to go to the net not on your own terms but because your opponent draws you in. Let’s look at Maria again. Her first few steps are a bit sideways as she moves in. Take a look at when the backswing occurs. Notice the stride with the right leg. As we mentioned earlier, when the right leg strides forward, the shoulders counterbalance the hips so the right arm goes back and promotes the backswing. The right leg stepping forward also naturally turns the shoulders which promotes core rotation. Note that the left arm stays in front which keeps the body from opening up too early. Keeping the shoulders slightly square is important since many recreational players run to the ball without swinging their arms but instead face the ball without creating a shoulder turn.

As Maria begins to swing forward with her right arm, she also strides forward with the left leg (or the opposite limb). When she makes contact with the ball, her legs actually return to a neutral (similar to a square stance rather than separated by a stride) position in the (anatomical) frontal plane. (For homework assignment, you can try a google search on “frontal plane.) As Maria finishes her stroke, the left leg continues to move forward. Her upwards or reverse follow through help decelerate her body and keep control of the ball in the court. The most famous net artist, John McEnroe, shows us the smoothest transitional footwork. There is almost no break of movement when he swings and contacts the ball. If you look closely at his back and forward swing, you will also see a very natural gait. McEnroe is quite smooth, with only a slight pause in footwork without breaking a stride. Again, note that synchronization between his right hitting arm and left leg as well as between his left arm and right leg. Practicing Movement As I mentioned, chances are, you will do this naturally. But sometimes we are over-trained in our mechanics and find ourselves doing unnatural things. If that is the case, you might need to break down your movement. Here are three things to keep in mind:

Here is a progression you might find handy.

Good luck this summer and I hope you get to a few more balls comfortably. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |