|

TennisOne Lessons Grips and Positioning for Successful Doubles Doug Eng EdD, PhD If you are a typical frequent player, you may be playing lots of league doubles. And if you like plenty of fireworks, being at the net in doubles is the most fun. The offense is usually started by a serverís partner, who can take advantage of a great serve or poor return of serve. As we all know, it isnít fun playing with a passive partner at the net. There are quite a few things you can do to help your side, but letís focus on two simple things that your can do at the net. These two ideas are: a) the serverís partner following the serve and b) a grip that favors action in the center of the court. Following the Serve In typical recreational matches, many players get very wary once burned by a great return in the alley. Then they slide over halfway between the doubles line and the center line to cover the another alley shot. But if you took tennis lessons, you were probably taught to stand in the middle of the service box or halfway between the singles sideline and center line. This stance allows you to be a bit closer to the action in the middle of the court. Since most returns go crosscourt, the server’s partner should stake his or her territory to favor the middle. When you cover the middle of the court, you can poach more easily and win more points.

But standing in the middle of the service box is only the starting point. You should move with your partner’s serve. As seen in Figure 1, start in the center of the service box and then follow the serve. After your partner serves, take a couple steps forward and then a couple steps towards the service placement or where the receiver must play the ball. For the serve down the center, in Figure 1A, get your momentum going by stepping forward and then towards the center. Step forward just before the serve bounces in the box. You should step towards the center just barely before your opponent actually hits. For the wide serve ( Figure 1B) again, step forward just before the serve bounces and then as your opponent hits, you take another step out to the alley. You should arrive in the correct position as your opponent is hitting. For the serve at the body, you may also move as shown in Figure 1A. When practicing following the serve, most players don’t realize where their feet are and often move incorrectly or don’t move before the return is struck. Sometimes, they drift a bit too far to the alley or center. If you move left or right too much or too soon, you telegraph your coverage and intention. It becomes easier for your opponent to pass you with a good return. So timing and moving correctly is very important. If your partner does not have great service placement, following the serve is very valuable. Sometimes partners discuss how they will construct the point but then the server hits the wrong half of the service box and the plan breaks down. Often, it is best to just follow the serve, rather than plan out the first three shots. If you are a 4.0 player or less, you may find this idea very useful. On second serves, this concept is even more important since many players can’t direct second serves as well. Even the less mobile 3.0 players I work with are able to increase their chances of net play by this simple movement. Following the serve involves reading the serve, the opponent, and incorporating footwork and movement.

Statistically, let’s look at what could happen in a match if you choose to guard the alley. In Table 1, we assume that 75% of returns go crosscourt. Assume the remaining 25% go in the alley and exclude lobs for simplicity. Let’s assume that the net player guarding the alley has a better chance than the player covering the crosscourt return in playing winning volleys. Hence, the player covering the alley is given a 20% and 50% chance of playing winning volleys. The player covering the crosscourt return is given a 10% and 35% chance of playing winning volleys. Even still, the player covering the crosscourt ends up ahead with a 28.75% chance of hitting a winning volley compared to only 22.25%. Given that the remaining points might be considered neutral (50-50%), it is evident that the player who learns to cover the middle has an edge. This number is a statistically huge edge and can turn a tight match into a routine win.

The mentality you should therefore take is to hunt down the balls in the middle. Even if one or two returns go into the alley and make you look silly, you should continue to play the odds in the middle. Following are two drills you can do with two friends. Serve and Step Drill Have a friend practice serves. Stand on the server’s side in regular net formation and practice moving a step in the direction of the serve. If the serve goes near the center line, step forward and then take another step to the center. If the serve is wide, step forward and then take another step towards the singles sideline. Two-on-One Deuce or Ad Court Drill

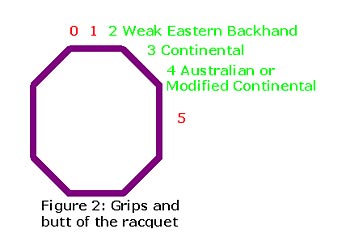

Practice a two-on-one formation with you and a friend at the net and the third player at the baseline on the other side. Have the baseline player directly across from you feed a ball as if a service return so you can practice the first volley from the center of the court or from the doubles alley. Then play out the rally. To make things more challenging, have the feed start from near the center mark or from the doubles alley. A variation is to put two players at the baseline and you alone at the net. You should practice moving forward and to the optimal position in the direction from where the feed is made. Favoring the Center Grip If you ever took lessons as a beginner, you might have learned to use the eastern backhand and forehand grips to volley. That is, you learned to use separate grips for your forehand and backhand. You were told to do that as the continental grip requires a bit of training of the wrist to control the racquet face. At some point, you were told to change to a continental grip because advanced players don’t have time to change volley grips and the continental grip is favored among touring pros. The reality is that many pros do vary grips on volleys. Some will stick to more or less a pure continental grip but others will change their grip, swing plane, and contact point to optimize effectiveness of the volley. The second reality is that when your opponent is at the baseline, you do have a bit of time to adjust the grip. That may not be the case for volley-volley exchanges at the net. . In Figure 2, we see the butt of the racquet where the racquet face runs up and down. Position 1 represents the traditional eastern backhand grip often used by one-handed backhand players for groundstrokes. If you put your index knuckle at position 5, you will get an eastern forehand grip. For volleying, we are primarily concerned with the index finger knuckle at positions 2, 3, and 4. An intermediate player is encouraged to use continental (grip 3) but is often compromised when volleying out of the comfort zone. Out of the comfort zone volleys include stretch volleys, wide low volleys, and high volleys. In the photos in Figure 3, we see the grips from eastern backhand (1), to what I call a weak eastern backhand (2), to continental (3), to Australian (or modified continental), 4), to finally the eastern forehand (5). I refer the grip 2 as the weak eastern backhand as it is used by many recreational players when rallying groundstrokes with a one-handed backhand. Often, they don’t move their hand enough when switching from a forehand to a backhand grip. They end up with a fairly flat backhand or even a slice rather than a great topspin stroke. Sometimes, two-handers let go and use a one-handed backhand that may also have a weak eastern backhand grip. But most two-handers will resort to slicing in this situation. On one-handed backhand groundstrokes, today’s touring pros will often place the index finger knuckle close to the 0 position which results in two or more knuckles between positions 0 and 1. This grip is the extreme eastern grip or the western backhand which some pros are using it to hit powerfully with a high contact point and heavy topspin.

Learning to adjust the grip slightly is a matter of habit which you may find uncomfortable or already do naturally. There are some people who find the pure continental grip quite comfortable for most volleys, so I do not advocate using it for everyone. But if you are the person who misses wide, high, and/or low volleys, varying your technique can help. Let’s look at a more couple video clips. In the first one, the Australian forehand grip is compared to the continental grip. On the high volley using the Australian forehand grip (A), it is easier the drive the ball back down into the court aggressively. In (B), the continental grip is used but the racquet face is more open and it is easy to overhit. The racquet face is difficult to close and even touring pros often move a bit to a forehand grip. That is not to say the continental grip shouldn’t be used.

If the volley is low or net-high, the continental grip is advantageous. But most poaches will be on higher rather than lower balls. When protecting against the return in the alley, using the same Australian forehand allows you to make the racquet face turn back into the court. Your contact point may also be a bit late without hitting wide (C). But using the continental grip is more likely to hit wide (D). Some players can use good wrist with a continental grip but if you don’t have the wrist strength, you may want to try the Australian forehand grip on the backhand volley in the alley. In the next video, we see the use of a weak backhand grip. On the high backhand volley, even if you are a two-hander, you can reach up and drive the ball a bit down into the court. Using a continental grip may result in overhitting the ball as the racquet face is very difficult to close on the high volley.

When protecting against the wide return in the alley, using a weak backhand grip on the forehand volley helps reduce use of the wrist to redirect the ball back into the court. Players with strong wrists can escape with the continental grip by flexing the wrist forward but it is easier to adjust the grip. Some players bend the elbow to turn the racquet face back into the court. Neither use of the wrist or elbow are easy. Using a grip that favors the center makes sense if you consider that most balls you want to play cross the middle of the court. It is not unlike waiting at the baseline in a groundstroke rally with a forehand grip if you have a big forehand. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to slightly favor the grip required for the center volley.

I call this concept “favoring the center grip.” The simple way to think about it is, you are always trying to be most aggressive on the crosscourt returns or the volleys in the center. It is not unlike waiting for a return of serve and waiting with a forehand grip if you have a big forehand. Therefore, it is not unreasonable to slightly favor the grip required for the center volley. Figure 4 shows a right-handed player which grip to use from the deuce or ad service box. Use the Australian forehand (or grip 4) when waiting in the left service box as shown in Figure 4A. Use grip 2 (or the weak backhand grip) if you are waiting in the right box (Figure 4B).

Any ball in the alley, you must redirect either back down-the-alley or back into the court. The red arrow (“out!”) shows what happens if you are late or can’t get around the wide volley with a continental grip. Some of you might ask, but the using the “wrong” grip might lose some power on the volley. My answer would be that rarely, off a wide alley volley, can you really hit a firm volley anyhow. Also, the down-the-line return is a heavier ball than a volley-volley exchange. For many players, it is easier to adjust off a wide volley-volley exchange. How can you practice this? Here are a couple very simple drills to conclude. I use these drills with players of all levels. Post to Post Angle Volley Drill

Stand halfway between the net post and and the service line. Have a friend stand on the other side of the net, halfway between the service line the other net post. Practice playing angled volleys using reverse grips: e.g., grip 2 on the forehand volley, grip 4 on the backhand volley. Use a bit of wrist cock (or extension) on the backhand to direct the ball back into the court. Angle the Alley Return Drill Now have your friend move to the baseline opposite you and hit a ball up the alley. Practice using grip 2 on the forehand volley and grip 4 on the backhand volley and angle the ball away from your friend. Make sure your friend doesn’t feed you too close and makes you stretch wide.

Rip the High Volley Drill Finally make your grip modifications and have your friend feed you shoulder-high, medium-paced balls through the center of the court. You should have an Australian forehand grip (4) on the forehand volley and the weak backhand grip (2) on the backhand volley. Practice a stretch poach and volley aiming the ball at where the receiver’s partner’s feet should be. Hit aggressively and move your feet into the shot. Finally, using the “wrong” grip on the volleys against the down-the-line pass can also be a successful technique. You will find that it will help you angle the stretch volleys back into the court. Good luck! Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |

When in a volley-volley situation, more or less a normal continental can be better for reaction volleys and low volleys. With the return of serve, there is often enough time to quickly cut across the net to poach and adjust the grip to make a more aggressive volley.

When in a volley-volley situation, more or less a normal continental can be better for reaction volleys and low volleys. With the return of serve, there is often enough time to quickly cut across the net to poach and adjust the grip to make a more aggressive volley.