|

TennisOne Lessons The First Step Doug Eng EdD, PhD One of the most common traditions in teaching tennis is the development of the ready position and the split step. Traditionally, teaching professionals address the ready position and split step as a static athletic stance with a hop off both feet and first step in the direction of the ball. Recently many experts suggest challenging alternatives to the traditional split step. We now look at the concept of unweighting (i.e., getting low by relaxing and flexing the knees before your opponent makes contact with the ball) and split steps that may be staggered (one foot landing slightly ahead in time to push off quicker).

I started a recent article by quoting Stefan Edberg: “everyone can hit the ball out there, but getting to it and getting to the right place at the right time is really what tennis is all about. It's really a running sport." We all know how important it is to quickly react and move to the ball. But what exactly is a split step? And how might you move the quickest? In this article, I will get away from conventional thinking of the split step and address other parameters that assist better movement. A New Look At Response Time and Anticipation Sport kinesiologists and movement experts have a general rule where the time to respond to a stimulus is equal to the time to react plus the time to move: Response Time = Reaction Time + Movement Time Unfortunately, anticipation is not accounted for in this classic formula. For many sports, however, anticipation can be a very important element. A modified formula is: Response Time = (-) anticipation + Reaction Time + Movement Time Anticipation can occur in “negative time” or before your opponent actually strikes the ball. Good players focus on relevant anticipatory cues well where novice players fail to recognize such cues. Reaction time is the time it takes for your pre-motor processing to occur. Movement time is the time for your motor movement to complete the action. Without anticipation, your response time is clearly the time to physiologically react and move. With anticipation, you might actually reduce the response time. Your movement time can be reduced by improved strength and fitness. Don’t Stop, Don’t Jump Club players tend to take fewer steps than touring pros. In fact, the better the player, the more adjustment steps they often take to get to the ball. Part of this argument is because a) better players are more athletic, and b) better players can move the ball around more forcing each other to move. But still, advanced players will have a faster turnover rate (e.g., the number of steps you take in a given time) and take more, finer adjustment steps to hit a better ball. Our own TennisOne editor, Ken DeHart, always says “no man’s land” is when you stop moving. It is harder and takes more energy to stop and restart than move continuously. For example, late model cars have computer MPG gauges and you can check how much more gas (or energy) your vehicle will use if you stop completely and then accelerate as opposed to coasting. It is easier to keep moving, even if slowly and then accelerate. Many top teaching pros have their young juniors always moving on the court even if waiting in line. Next time you jump into a group drill, try to keep moving your feet even if waiting in line. You will get a better workout and also develop better movement habits. The father (and coach) of Marion Bartoli, the 2007 Wimbledon finalist, used to attach tennis balls to the heels of her sneakers to keep her off her heels. This unusual exercise also promotes constant movement.

A split step that involves a vertical two-footed hop in the air often loses time. You still need to unweight by flexing the knees but this doesn’t mean a high jump but a small, quick efficient hop. Some players literarily jump too high which is a sign of over arousal. A high split stepper loses valuable time in the air. The classic inverted U of the Yerkes-Dodson Law suggests that performance peaks at an optimal arousal but with over arousal, performance decreases. Many experts believe that over arousal can reduce reaction time. Nevertheless, this point is debatable as research is inconclusive. However, in my experience, over aroused players tend to a) become narrowly focused or b) fail to tune into environmental cues. As a consequence, they tend to not read anticipation cues well and react slower. In addition, over arousal interferes with relaxed movement which affects movement time. Anxiety increases reaction time. Therefore a relaxed but alert (slightly aroused) tennis player can react quicker. In artificial intelligence, researchers formulated what is known as Hick’s Law which refers to as choices increases, so does response time. Although Hick’s Law was invented for computers, it has a bit of truth for people. When faced with choices, it is easy for us to overanalyze and overload our brain. It is easy to become indecisive and make an unforced error rather than decisively hit a winner. Indecision can also contribute to poorer anticipation. If you can anticipate extremely well, my guess is that your anxiety level will be low. If you are clueless, it is easier to become more stressed and therefore, react slower.

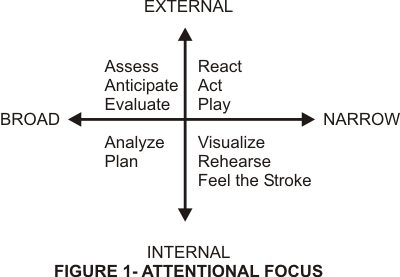

Be the Ball You might know this famous quote from the movie Caddyshack. It emphasizes an out-of-the-body experience or an intense focus on the ball. Sport psychology Robert Nideffer defined attentional focus as having two axis: the internal/external axis and the broad/narrow axis. Your focus can be described as a combination of the two axes. In tennis, the narrow-external focus is most important for reaction and movement to the ball. The broad-external focus is critical for anticipation when you read environmental, court, and opponent cues. That is, you broadly absorb information from several sources to anticipate well. As you opponent strikes the ball, your focus should very much be on the ball and movement phase that demands a narrow-external focus. Therefore, a primary factor of response time is your narrow-external focus. Your split-step is a part of this phase. Staying primarily in this phase means staying in the zone. According to attentional theory, the zone or flow state is achieved when you are able to stay primarily in one appropriate quadrant (for athletics, the narrow-external focus). When a player tends to focus internally, it is easy to lose the flow state. In fact, the classic tome Inner Game of Tennis addresses this as the critical mental Self 1 which tells the physical Self 2 what to do. So even though we need to be internal at times, we don’t really want to focus on it for tennis. The internal focus is important particularly in the time between points.

Poor focus can also cause a mistiming in the split-step. Many club players also split step before they really know where the ball is going. They are trained to split when their opponent makes contact but because they don’t really recognize what to do next, they simply land on two feet without pushing off. Rather they have to stop and restart their momentum after landing. Other players simply split and prepare too late. In fact, it is very common for recreational players to not even split and prepare their racquet when the ball bounces. If the ball bounces around the service line, they have fairly good timing but when the ball bounces near the baseline, they are frequently late. Timing, anticipation and attentional focus are very important to allow you to move smoothly. Very much a part of playing in the zone is timing of the split step and the ability to float around effortlessly on the court.

Classical research has suggested, although far from being conclusive, that introverted people react and move slower to stimulus than extroverted people. They might actually anticipate or mentally figure out things on the court quicker but can’t elicit a faster response time. So perhaps better athletes tend to be more extroverted. In particular, we see many outstanding team athletes shine off the playing field with outstanding people (extroverted) skills. Since it is an individual sport, tennis is one of the less extroverted sports, however, which might balance things out. That is why you might know some people who get really focused on their emotions and strokes (narrow internal focus) and can’t really compete well. Or kinesthetic intelligence goes hand in hand with extroversion. Visual focus is also a limitation for many. Experts in sports vision show that many less accomplished athletes in particular in sports like tennis or baseball don’t focus their eyes well on the ball. They are easily distracted by other stimuli or their focal point wanders away from the ball, even if they think they are focused. Keeping your head still, like Roger Federer, is a great way of keeping focus. In any case, it is clear you need to develop strong a narrow-external focus to move better. Drills to Help Improve Focus Here are three simple drills to “be the ball” or develop a better narrow-external focus:

The ability to change focus from a broad-external to a narrow-external can be very valuable to assisting faster movement to the ball. For example, if you watch your opponent’s serving ritual, tossing motion, and sense the windy conditions (e.g., a broad-external focus) and then narrow in on the ball at contact (e.g., a narrow-external focus), you are able to react quickest. Here are a couple good drills to practice picking up broad cues and then narrowing in on the one most important cue (e.g., the ball)

I think after these exercises, you will find yourself a bit more focused on reading the really important cues that make you react quicker. The Zone, Relaxed Alertness and Heart Rate Research shows that at moderately elevated heart rates, we are most alert and can achieve flow or be in the zone. This makes sense if you consider that if you are not pumped up for a match, you might feel less energetic and therefore have a low heart rate as you won’t exert yourself much. On the other hand, if you are really excited and nervous about playing, it’s easy for your heart rate to go up too high. In that excited state, you might be too anxious and not able to be in the zone. The key here is to achieve a relaxed state where you are relatively calm. Your reaction time is also closely related to the zone. Think about when you are playing your best; of course, you react quicker than ever. Everything seems to come easy. Researchers have shown that with a moderately elevated heart rate, you react fastest. The heart rate (115 bpm) is a bit lower than what we normally play during tennis but the point should be well-taken. If you don’t become over aroused, your reaction volleys just might make the ESPN highlights. Some researchers found that a slightly anxious state reacts fastest. What that translates to is simply: if your heart rate is slightly elevated and you are alert (slightly anxious) for the ball, you will react fastest. Slide and Pivot Jumping too high on the split step is sometimes wasted energy. I remember having one player who played #1 doubles for us and he was extremely energetic. He was a great athlete but he also hopped too vertically on his opponent’s serve getting about 12 inches off the ground. By the time he landed, the serve was almost bouncing in his court. His athleticism allowed him to still get to the ball, but it was inefficient use of his speed. Venus Williams is annoyed by Ana Ivanovic’s return of serve. Why? Just listen to Ana’s feet. She isn’t the fastest player on the tour but her sneakers slide and squeak around on the court. That tells you two things about her footwork. Ana doesn’t come off high above the ground but rather she remains fairly close to the ground. Second, her numerous squeaks signify the high amount of small steps she takes and the efficiency of her footwork. Try this exercise in video 1 above: let your knees flex and relax (just before your opponent makes contact with the ball), then hop forward trying to keep both feet very close to the ground. It’s more of a slide forward and on a hard court, you might make a squeak as your soles rub against the court. Then try to constantly move getting ready to receive serve making as many squeaks as you can. You might have heard the expression “happy feet” and in this case you could call it squeaky feet. I don’t suggest making it an annoying habit to your opponent, but a couple squeaks is healthy.

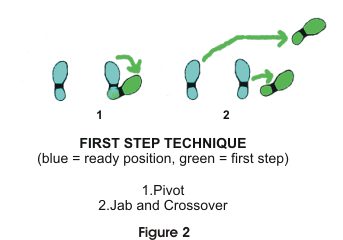

I call this drill the “Slide and Pivot.” After your squeak, you slide your foot closer to the ball in the direction of the ball (so the toes point to where you want to go). You don’t want to jump upwards but keep the feet low. The word pivot refers to the foot turning outwards without a step or a very small step. Many touring pros use this technique on a return of serve that requires a modest reach since it is faster than jumping into a split step. Since you don’t really get much off the ground, you may not get the same push-off to move greater distances as in the traditional split step.

Split, Jab and Crossover The split and jab (video 3 above) refers to a normal split step that gets you off the ground slightly and the step out. When your foot merely turns outwards (with part of the sole remaining on the ground), I call that a pivot but when you deliberate take a small step off the ground and turn it in the direction of where you want to go, that becomes a jab step. Some people naturally don’t like to slide, drag, and squeak their shoes on the court. The split and jab is better if your opponent is playing groundstrokes rather than serving since you have a bit more time and also you can get a bigger push off the feet. Simply turning out doesn’t let you push off as quick over a longer distance. Use this technique to move to wider groundstrokes. If you really have to run, after the jab step, you’ll have to use a crossover step (where the next step after the jab is with the other foot) which turns the hips fully so you can run to the side. Many club players instead use shuffle steps to get to the ball which keeps the hips facing the net. Unfortunately, in shuffle steps the hips are not turned to the sideline which renders this type of movement impractical for making sprints parallel to the baseline.

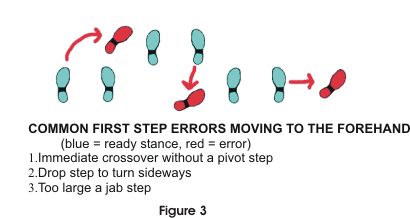

You should avoid three common pitfalls that club players make. The first is that many players often take the foot farther away from the ball and make a crossover step immediately. That eliminates a push-off on that foot and leaves out the jab step. Often they will react slower. The second is using a drop step (think of a backwards jab step) to move laterally. (The drop step is used to move backwards). Many people often think they need to turn sideways first with the feet and make these two errors.

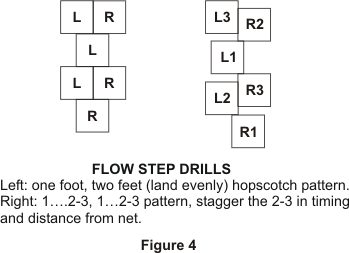

Gravity and Flow Steps The gravity step (video 2 above) uses your height and loss of balance (or center of gravity) to help you move. When you watch baseball players or soccer goalies lunge and dive after the ball, they are using their initial loss of balance to make the fastest, widest move. In tennis, the only real situation this might occur is on the volleys and in trying to retrieve your opponent’s big serve or overhead. Boris Becker made the dive volley famous. The gravity step is often used moving to the net in combination with a split step or a flow step. A touring pro might split step and then narrow the stance quickly allow gravity to create momentum towards the ball. You might think of the flow step as a single footed split step or a staggered split step. Think of the old children’s game hopscotch. When you go to or from one foot, that is very similar to the flow step. Continuing flowing from one foot to the other rather than landing on two feet in a traditional split step. Therefore you are staggering your split step so they don’t land parallel to the net.

You can improve your movement with a couple drills: 1) visualize a hopscotch pattern chalked on the tennis court and practice moving your feet into the boxes, 2) then visualize the same with a staggered pattern and practice a 1…2,3 rhythm. For example, hop on the right foot and then land in quick succession on the left and right feet almost together. In the beginning it is a bit tricky but once you get the hang of this, it’s a great exercise like running on an agility ladder. It is important to note that when moving to the net, you don’t want to stop moving but you must have control over your forward movement. In this way you can adjust your momentum or balance as you move towards the ball to play your volley. Summary Singles, in particular, is a game of movement. To move faster, consider non-movement factors that you can improve:

Consider several movement factors you might want to add to your practice play:

What we see here is an integration of technique, fitness, court intelligence (e.g., anticipation) and sports psychology (e.g., relaxation, attentional focus). Merely practicing a split-step, jab step, or gravity step isn’t practical if you don’t include other factors such as anticipation and attentional focus. In addition, there are plenty of off-court exercises you can do to improve your movement. Realistically, your hitting or practice sessions should incorporate and integrate little bits of different areas to make you a better player. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |

By remaining mostly in the narrow-external focus, you might avoid some common misbeliefs. Some people focus too much on their “game” meaning strokes and how they feel about their strokes and others focus too much on trying to keep the ball in or on winning. These broad-external foci includes evaluating a shot or game and attaching emotional qualities to the results. They focus too much on the outcome (win or lose), quality of their strokes and their emotions. Unfortunately, they become good hitters or steady pushers, whose mental Self 1 give them a difficult time because they attach value to each stroke and react to them. Focus does not well shift to the present which is narrow-external (react, act, and play).

By remaining mostly in the narrow-external focus, you might avoid some common misbeliefs. Some people focus too much on their “game” meaning strokes and how they feel about their strokes and others focus too much on trying to keep the ball in or on winning. These broad-external foci includes evaluating a shot or game and attaching emotional qualities to the results. They focus too much on the outcome (win or lose), quality of their strokes and their emotions. Unfortunately, they become good hitters or steady pushers, whose mental Self 1 give them a difficult time because they attach value to each stroke and react to them. Focus does not well shift to the present which is narrow-external (react, act, and play).

The third is taking too big of a jab step which makes you lose momentum. Last year, a commentator mentioned that Justin Gimelstob was never a great mover because he took too big of a jab step. I find that many beginners think they have to be balanced for every shot so instead of letting the loss of balance in a gravity step work for them, they try to regain their upright balance by taking a series of jab or shuffle steps. This footwork leaves them facing the net on the wide volley and taking a backswing rather than turning the shoulders and stretching.

The third is taking too big of a jab step which makes you lose momentum. Last year, a commentator mentioned that Justin Gimelstob was never a great mover because he took too big of a jab step. I find that many beginners think they have to be balanced for every shot so instead of letting the loss of balance in a gravity step work for them, they try to regain their upright balance by taking a series of jab or shuffle steps. This footwork leaves them facing the net on the wide volley and taking a backswing rather than turning the shoulders and stretching.