|

TennisOne Lessons Modern Approach Shots Tactics Doug Eng EdD, PhD Hard Court Analysis A few months ago, I discussed the effectiveness of approach shots on grass courts. It was found that the inside-out forehand was the most effective approach. It was also found that, in general, the forehand topspin drive was more effective than the backhand slice. In this article, let’s move the discussion to hard courts. Our sample has 300 approach shots played at the most recent US and Australian Open with sixteen players, half of whom were in the Wimbledon study: Agassi, Blake, Ginepri, Federer, Baghdatis, Ljubicic, Roddick, Robredo, Nalbandian, Hewitt, Mirnyi, Gasquet, Grosjean, Kiefer, and Safin. All players and opponents were right-handed.

In Table 1 – Part A, we see a summary of the basic types of footwork. There was a strong propensity to use forehand approaches (73.0%) almost as high as at Wimbledon (78.4%). Most one-handed backhand approaches with the carioca step were played with underspin with a 44% winning percentage -- I use highlights to make it easier to refer it. Overall, all shots played with underspin won only 42.1%. On grass, underspin was more successful at 62.5% but well below topspin approaches which won around 75% of the points. The relative lack of success of the slice approach might surprise many but is probably why it is rarely played among ATP players. On hard and grass courts, only 6.3% and 9.6%, respectively, of all approaches were played with underspin. Rather, the modern slice is used primarily at the baseline under pressure since it gains time, is consistent, saves energy and can neutralize an opponent. Still, at the club level, there may be circumstances that favor use of the slice approach.

In Table 1 - Part B, shot directions are classified. The forehand crosscourt was a lowly 41% successful. You may expect this failure if you have been taught to a) not hit crosscourt approaches and b) hit to a weakness (e.g., backhands). Highlighted in green are the success rates of two approach shots played from the center lane of the court (rather than the far 1/3 ad court or far 1/3 deuce court). In Part C, it is seen that approach shots played from the center lane are most frequent (40%) and successful (72.5%). (A few years ago, Nick Saviano once discussed this trend). Traditional approach shots are taught to be played down-the-line from the outside 1/3 lanes (ad or deuce court lanes). However, the big forehand in the center lane may be most difficult to anticipate, much less return a passing shot accurately. In a previous article, the effect of origin (i.e., how far inside the baseline was the approach shot played) and footwork was examined. For example, most static forehand approaches are played from close to the baseline. Dynamic footwork occurs on balls that are usually farther in the court forcing the attacking player to move forward. We might surmise that players with static footwork may be big-hitters such as Andy Roddick. For such players, volleys are rarely strengths, so the static footwork near the baseline may be less successful. Table 1. Approach Shots on Hard Courts

Table 2 compares the three major forehand footwork types: the dynamic open stance, the dynamic back kick with a square stance, and the static open stance. The back kick is played with a square stance and with the back (or right foot for a right-handed player) kicking back transferring weight forward. Table 2 examines whether the origin differed between points won and lost using these footwork patterns. Statistics are given and the final value, the Z-score is at the right. If the Z-score is greater than 1.96, we would be 95% certain that there is a difference between the points won and points lost. As we see, none of the Z-scores are more than 1.96. The points won and lost with the dynamic back kick averaged 8.5 and 6.9 feet inside the baseline, respectively. This difference was, however, statistically insignificant with a z-score of 1.44. To be 95% certain, the won points must be 2.27 feet (rather than 1.6 ft) farther inside the baseline than the lost points. We see that our hypothesis that the static approach shot is less successful is incorrect. The static forehand at a 69.5% success rate was as successful -- if not more -- than the two dynamic shots. The static open stance was played 2.98 ft inside the baseline on points won whereas the dynamic footwork averaged 6 to 9 ft inside the baseline. For the dynamic square stance with the back kick, points were won merely 69.2% of the time despite being an average of 6.88 ft inside the baseline on even lost points! That is to say, you could start closer to the net, move through your shot, and get to the net earlier, but your chances of winning don’t increase! (Note this does not mean don’t hustle in!) Table 2: Statistical Analysis of Origin and Winning Points

Why is the static approach shot so successful despite being so far away from the net? First, players can load better to hit bigger forehands if barely moving instead of hustling forward. Second, hitting with pace away from the opponent might be a more important factor than footwork. By hitting harder off the static stance, one might give opponents less options and control of passing shots. Third, the agility at the net or the volleying skills of the attacker may be more important for success than getting a few feet head start moving forward. Hard Court Vs Grass Court Table 3 compares the hard court vs. grass court results. On fast, low-bouncing grass courts, it is more difficult to hit a passing shot. Plainly, the success rate of the forehand on grass is more successful than on hard courts where the bounce is more predictably easier for the defender. Notable is the inside-in forehand from the center lane to the opponent’s forehand which had a success rate comparable to the down-the-line or the inside-out. On either surface, the backhand approach shots were generally less successful. Table 3. Forehand Approach - Grass Court Vs Hard Court

Although origin and footwork may not be critical to success at the net, please note this information is statistical (not absolute!) for touring pros. Club players differ in skills so your personal success may differ. For example, you may lack a big forehand and your opponent might not have a pass off your slice. If so, you should use a slice approach shot. Or you may have poor foot speed and therefore you need to get a short ball to get good net position. Figure 1 compares the success rates of origin of approach shots on hard and grass courts. We see players near the baseline generally have near 70% success rate on either surface (far left on Figure 1). Well inside (12 ft or more) the baseline, the surfaces also did not matter as the success rates converged around 75-80%. There were, however, major differences 3-11 ft inside the baseline. On grass courts, approach shots were still highly successful. On hard courts, the approach shot had lower success. Why? Many of these approach shots are not on the attacker’s terms but usually on balls that they are forced to use dynamic footwork and may even feel slightly rushed to play the shot. Ball height might also make a difference although it was not measured in this study. On grass court, the passing shot might be difficult regardless of origin but on hard courts, the defender may be able to pass more easily. Therefore, pros should hit approaches on their own terms rather than merely wait for short balls. Figure 2 compares the success rate versus depth of the approach shot on hard and grass courts. There appears a modest increase in success for approaches that bounced slightly short on both surfaces. These shots may include chips or fast-paced topspin balls that bounce short -- possibly bounce twice around the baseline. Low at the baseline, these short balls can be problematical for the defender who doesn’t move quickly in from the baseline. On hard courts, the lowest success rates were obtained on the deepest struck balls! (This statistic does not include balls hit out of court considered immeasurable). As Eliot Teltscher once commented, shorter may be better as hitting your approach shot deep may involve hitting to your opponent’s comfort zone. Touring pros often anticipate deep approaches and move back slightly to play the passing shot. In addition, automatic reactions may play a role on the deep pass. We sometimes hit amazing volleys with little time to react and we are at a loss to explain. We also sometimes hit amazing returns off service faults. You are faced with little time and tend to relax as you know the serve is already a fault. You become relaxed, automatic, and instinctive. Most importantly, the success rates were always above 66% in Figure 2 regardless of the depth. So regardless of depth, pros have very good chances. But those occasional chips and short fast-paced topspin balls do win at the pro level and might surprise your opponents.

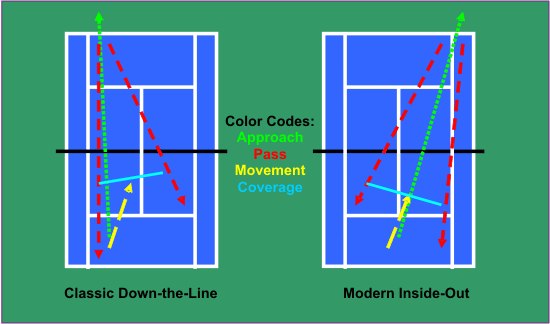

Figure 2: Depth vs Winning Percentage Court Geometry of the Modern Approach Shot The inside-out forehand may be used as your primary approach shot if you have a fairly big forehand, have reasonable quickness, and have a 4.0 NTRP rating or higher. This is not to say if you are 3.5 or lower to avoid this marriage of technique and tactical play. Rather you should aspire to it. At the 3.0 level, hitting a big forehand even down the middle of the court forces weak replies that can’t be properly directed. In comparison, the classic approach shot is played with underspin and down the line from the outside thirds of the court. The rationale for using slice is to keep the ball low to make the passing shot difficult. At the club level, hitting the slice particularly to a player with a western forehand or a two-handed backhand is advantageous since club players don’t have the athleticism of professionals. Underspin also takes your opponent out of rhythm. Figure 3 shows the court geometry for the classic down-the-line and the modern inside-out approach from the center lane. In both diagrams, your approach shot is the green line. You move along the yellow line to cover the court properly and you cover the possible replies (blue line). Since you will probably hit the ball harder using the inside-out forehand, you end up stopping farther away from the net whereas a slower slice down-the-line may allow you to get closer to the net (longer yellow line). Hence, the blue line for the left diagram is closer to the net and slightly shorter. You may be able to cover this entire blue line even if your opponent can hit a reasonable down-the-line pass or angled passing shot (both shown in red). The longer blue line in the right diagram represents more court to cover and has been a rationale for not crushing approach shots. The same concept has been theorized for using spin serves to play serve-and-volley tactics.

There are a couple assumptions for the down-the-line to work: a) being closer to the net translates to more winning volleys, b) you can cover the blue line. However, those assumptions may not hold. First, being closer to the net means you have less time to react if your opponent crushes his or her passing shot which happens frequently today even at the pro level. Second, you can be more vulnerable to the lob. In addition, after hitting the down-the-line, you don’t necessarily move straight forward to the ball as some people think. You must move ever slightly away from the ball path to the middle to cover the crosscourt pass. You remain on the same side as your approach shot as to also cover the down-the-line. At the professional level, especially on clay courts, a popular passing shot is the topspin crosscourt angle known as a dipper. With modern, lighter racquets, the dipper has become easier to play. It was more difficult to play with older wooden racquets when the down-the-line theory evolved. To hit the dipper, the defender must change the direction of the ball (i.e., hit a crosscourt off a down-the-line). If the player doesn’t change direction but goes down-the-line, it is riskier and easy to hit wide of the court. Theoretically, changing directions off a slower ball (slice) is easier than changing directions off a hard-hit ball (inside-out). Therefore, hitting a crosscourt dipper is a high percentage play off the slice down-the-line approach. At the professional level unless the attacker really closes the net, the crosscourt dipper is very dangerous.

On the right in Figure 3, the inside-out forehand is shown. The assumptions for using this shot are: a) you can hit a big forehand, b) your opponent is weaker on the backhand. You cannot close as quickly since you have less time especially if you are using static footwork. So you are a bit farther away from the net and must cover a longer blue line. There are some advantages, however. First, you are moving in the direction of the ball so you don’t need to move away from the ball to cover the crosscourt. Second, you can move your opponent off the court whereas a down-the-line keeps your opponent inside the sidelines. It has been argued that the down-the-line pass becomes easier as the attacker cannot cover it. But is it really that easy? Even pros often lack enough control off the big inside-out forehand to consistently place the down-the-line pass on the run. Flirting with the sideline is not a high percentage play. In addition, the crosscourt dipper is difficult to execute since few pros – much less club players – can produce great angles off hard-hit balls when on the run, a la Nadal. Although theoretically the blue line should be covered, the big inside-out reduces the defender’s accuracy and options. In summary, the down-the-line approach shot is about positionally setting yourself up for volleys closer to the net but the inside-out forehand approach shot is about making life difficult for your opponent on the backhand side. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Camps at Harvard. He has received divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national award. Doug completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. Doug also writes and speaks on tennis and sport science. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||