|

TennisOne Lessons Warriors and Zen Masters How our Mentality Impacts Playing Styles and Training Doug Eng EdD, PhD Whether beginners or ranked open division players, all have particular styles of play. In the professional ranks, we see the aggressive baseliner and the all-court baseliner. The aggressive baseliner powers up from the baseline while the all-court baseliner will rally from the baseline and looks to finish off points inside the baseline. There are also the traditional counterpunchers and the serve-and-volleyers. Although these styles hardly exist at the pro level any more, they certainly flock around the courts you and I play on. Some players have a quiet approach to playing like Ana Ivanovic, Pete Sampras, or Roger Federer. They rely on staying calm and in control throughout the match. Other players show their fighting spirit on what seems like every point, like Lleyton Hewitt, Jelena Jankovic, or Rafael Nadal. To play well, they need to fist pump and run hard. I call the cool controlled player the Zen Master. The player who loves to run and fist pump is the Warrior. In Table 1 I've listed some warriors and zen masters.

What we’ll explore here is the relationship between personality, arousal, playing style, and training. Often your choice of playing style, skills, and tactics match your personality and mental skills. In addition, physiology and training also are impacted. In the following article, I make some generalizations but as we all know, there are exceptions to each rule. We are, after all, only human. Let’s see how all these things are related. The Mental Base Aggressive baseliners take control from the baseline. The net is secondary and few points are played with the intention of finishing there. Many baseliners say they’d like to get better at the net and their teaching pros or coaches wonder why they don’t go to the net more.

I think there is a chain of thinking and actions that create the aggressive baseliner. This chain is hard to break once the player has a playing style ingrained. In fact, in this chain or evolution of a tennis player, everyone starts as a baseliner. That is, most beginners feel comfortable letting the ball bounce. Every beginner lets the ball bounce because they perceive that’s how tennis should be played. Everyone should rally after letting the ball bounce, right? In fact, complete beginners typically rally back and forth letting the ball bounce without serving, volleying, or keeping score. For a complete beginner or non-competitive player, rallying is playing tennis. At the top of Table 2, we see that virtually everyone’s perception of tennis starts at the baseline. Ironically, many children actually make better contact volleying the ball since the ball in the air follows a simple trajectory. A ball that bounces follows a more complex trajectory. The brain must recalculate the trajectory since spin and surface changes the ball’s trajectory. For many children, it isn’t easy to hit the ball after the bounce. We often see young children stand at the net and make easy volleys but when they move back, they misjudge the ball, letting it hop over their heads or swing without making contact. Some people are not natural risk-takers. They are stressed by roller coasters or gambling and rather stay at home and read a book or watch a movie. In tennis, many people don’t like missing. Their idea of good tennis is being able to rally so their base mentality (see Table 2, Line A) is consistency. Other people naturally like risks. They don’t want to wait until an opponent misses. So they take chances to win the point.

We often stereotype boys as more risk-taking than girls. There is biological root to this as females are the protective half of our specie and males take risks in order to attract females. Today, biological differences may be masked by societal belief in gender equality. The great part about tennis is that (thanks to pioneers like Billie Jean King) it is the most gender-equal of all traditional sports. Players who take risks or go for shots are not content to rally at the baseline. They are likely to play a drop shot, go for a winner, or charge the net. In Table 2, we see that physical skills of a risk-taker often require fine motor skills to play angles, volleys, or drop shots. A creative player like Martina Hingis or John McEnroe does not like grinding out points. The ability to grind out points is the trademark of a counterpuncher or an aggressive baseliner. Baseliners rely more on running and gross motor skills to play groundstrokes. The counterpuncher has the best shot tolerance (Table 2 line E, phrase was coined by Eliot Teltscher) which is the ability to play the same shot again and again. Rafael Nadal has the best shot tolerance of any pro. He knows how to stay in a rally and not pull the trigger too early. Nadal serves almost exclusive to Roger Federer’s backhand. That singular determination is extreme shot tolerance. Shot tolerance is also known as patience.

I refer to line F in Table 2 as Base Personality. Counterpunchers by nature are not creative but are warriors who grind with intensity. They are often meticulous in preparing for matches. They are the mentally toughest opponents since they refuse to make errors even if it means being a passive defender and never attacking. Aggressive baseliners have less patience or shot tolerance. They want to take charge from the baseline so I call them A-type personalities in a tennis-sense. Of course, this is not entirely true but we are trying to develop a model. On the other hand, serve-and-volleyers take high risks and to tend to be more relaxed rather than intense. Relaxation is very important to shot-making especially volleys. Daryl Fisher in Effortless Volleys recently tackled relaxation and volleys for TennisOne.

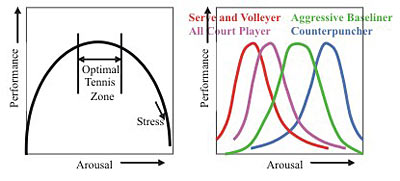

Arousal and Playing Style In discussing playing styles, the concept of arousal rarely comes to the mind. Arousal, however, is an important concept in sports psychology. The classic Yerkes-Dodson inverted-U theory (Figure 1) suggested that at a specific arousal, performance is maximized. You could think of arousal is as energy required to activate performance. In 1980, Hanin suggested an individual zone of optimal performance theory, implying each person achieves peak performance differently. In addition, Weinberg and Hunt (1976) suggested that a task requiring fine motor movement, such as playing the violin or making a golf putt, requires less arousal. On the other hand, running the 100 m sprint requires gross motor control and hence, a higher arousal or activation level. In Figure 1 (on the right), we classify arousal-performance relationships for different playing styles. Heart rate is fairly correlated with arousal. In a few studies, the average heart rate of tennis players was between 140-165 bpm. If you are not running hard but your heart rate is fairly high, you are probably overaroused and your heart measures both exertion and anxiety. A relaxed player will produce more effort for the same heart rate as a tense player since anxiety alone can cause an increase in heart rate. There is considerable research literature on the biochemistry of stress. You might have heard of the fight-or-flight response and the secretion of corticotrophin-releasing factor (a hormone) and norepinephrine. In turn, adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH) and cortisol are produced to increase heart rate, body metabolism and a heighten awareness. Incidentally, these last two hormones are responsible for insomnia and your internal alarm clock to wake you up on time. In Figure 1 (left), this excess stress (see arrow on the curve) could shift the arousal higher out of the optimal tennis zone.

There isn’t much research, but I would guess that serve-and-volleyers who need to play finesse, controlled volleys ideally operate at slightly lower heart rates and anxiety levels than counterpunchers who run down many balls in longer points. We are looking at probably heart rate differences of 10-25 bpm (e.g., 150 vs 175). So in the overall spectrum of arousal, the right side of Figure 1 is a relatively small range, but still significant in terms of peak performance and training. If you are a counterpuncher who relies on running down many balls, you will be higher aroused and will use your gross motor skills more than a finesse serve-and-volley player. Therefore we see in Figure 1, on the right, we can classify arousal-performance relationships for different playing styles. In addition, if you run until you are short of breath, you will lose some fine muscle movement and precision in your shot-making. Recently some researchers developed what is called a Loughborough Intermittent Tennis Test (LITT). In this test, players ran and struck groundstrokes in a set pattern and time. The players then served at match pace and the serves were measured for accuracy. The more the players ran, the less accurate their shots. That seems obvious, doesn’t it? The point here is that if you ran hard and hit hard for a couple points, it is challenging to change up pace and go for a finesse shot out of the blue. Late in a long match, fatigue and nerves come into play even if you haven’t been pushed hard. A good example in another sport is basketball. Some teams play a very physical defensive game that requires high arousal and expends much energy. Late in the game, these teams after hustling all day and taking hits and bruises, often miss seemingly easy free throws and open three-point shots which require finer motor skills. But a team that is used to fast break finesse style finds it easier to keep up that pace. Translated to tennis, zen masters with excellent touch and court awareness need to stay calm and focused on big match points. They need to still come up with the fine passing shots, angles and drop shots. Warriors often are better at simply running and hitting hard on big points. That’s the difference between Federer and Nadal or McEnroe and Connors.

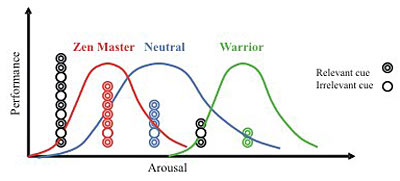

Furthermore, under high arousal the perceptual field tends to get narrow according to Easterbrook’s cue utilization theory. Consider that there are relevant and irrelevant cues. When John McEnroe notices someone in the stands cheering against him, he may be distracted from his tennis. The person in the stands represents an irrelevant cue. When you focus on your opponent’s toss on the serve and split step just before contact, you are tuning into a relevant cue. Under great stress, we often make poor decisions since our judgment and perceptual field is severely reduced. So a player who tends to run hard and crushes the ball from the baseline is best just playing that way. We all know someone who bashes the ball sometimes without a clear strategy. A while back, Kim Clijsters and Mary Pierce had their critics since, in big matches, their game plans seemed too simple: bash the ball. Many also criticize Andy Roddick for doing just that. Andy has added more to his game but critics feel his serve could be improved. But you can’t turn a 300 pound wrestler into a 100 pound ballerina. The warrior best thrives by playing his or her own game regardless of what the opponent does. When asked about Mary Pierce, Nick Bollettieri commented that she needs to just hit the ball and not think. The warrior can zone and strike the ball exceptionally well but may seem not to notice chances to go to the net or may hit repeatedly to the opponent’s strength. They only see a couple relevant cues and miss the others.

You sometimes hear commentators ask why don’t some of the top ten WTA pros go to the net much. Rather it seems they play, in Mary Carillo’s words, “big babe tennis.” That means hit hard through to the baseline. Drop shots, approach and volleys, topspin lobs all seem to be afterthoughts. The fact is that many of these players like Dinara Safina are warriors. The warrior wins with high intensity not finesse. Rafael Nadal is the supreme warrior. He even looks like a warrior when he used to wear the sleeveless shirt and flex his muscles. Even still, as everyone is human, we all have variations. Nadal has supreme touch and control, too. He has modified his game to be more offensive. Nevertheless, his true nature is the supreme retrieving warrior. A warrior needs to work harder than his opponents. That’s why we see Dinara Safina become so good in the past year. Her fitness level improved immensely allowing her to play as well as she can. Before Rafael Nadal, there was Jim Courier, Michael Chang, and Tomas Muster – they trained very hard to maximize performance. The game plan becomes simple. In Nadal’s case, his service game against Roger Federer is ultra simple: almost exclusively serve to the backhand. In the cue utilization theory, high arousal tends to narrow the perceptual field and cues. In Figure 2, we see that warriors (in green) processes the fewest cues but they tend to be relevant. For example, Mary Pierce may only be concerned with the ball and not her opponent’s position. I really enjoy watching Gael Monfils. But like many tennis viewers, for the longest while, I couldn’t understand why he stays back so much and counterattacks. With his power and athleticism, he plays too defensively. Gael says that’s the way he likes to play. And that actually makes sense when you realize he is a warrior.

Zen masters tend to make tennis look effortless. They rely on court awareness and shot-making. They operate at lower arousal levels which suits the finer shots and greater court awareness they need. In Figure 2, you can see that the zen master’s arousal is on the left where they can pick up more cues. They can also pick up irrelevant cues such as John McEnroe when he gets distracted by someone in the crowd or a bad call. Roger Federer’s fifth set collapse against Nadal at the 2009 Australian Open is typical. Federer was probably overcome by the moment where perhaps the pressure of history (i.e., winning a record-tying 14th major title) was too great. Nadal, on the other hand, couldn’t care less. He wasn’t trying to make history, he was trying to beat someone who was greater than him. Nadal’s approach was determination to show he can win on a hard court against the greatest player in his mind. He took the role of underdog and had nothing to lose. Because zen masters rely on shot-making and court awareness, the physical side is often less important. We see Marcelo Rios, John McEnroe, and Martina Hingis all under train. Even Federer has his critics. I will elaborate on training later. Many club players have a hard time playing finesse shots. That is because they might grip the racquet too firmly, are gross-motor skilled, or are highly aroused. In any case, these players are better off being warriors or baseliners. They need to pump up for matches. A warrior usually doesn’t try to outsmart his opponent but either outruns or out-bludgeons his opponent. On the other hand, a player who is easily bored tends to also be easily distracted. Beginners who are not interested in the task at hand are excellent examples. There is some research on sports vision, particularly the ability to focus with the eyes. These studies show that many inexperienced athletes don’t focus on the main target (e.g., the ball) well. Often beginners don’t understand which cues to focus on. By not noticing when the ball is struck or the face of the racquet in the opponent’s hand, a beginner often fails to be ready when the ball bounces in front of them. The beginner often misses these important external cues, since he is focused on internal cues.

A beginner at the verbal cognitive stage of learning is having enough problems just trying the use the right grip, take the backswing, swing to the contact, and follow through over the shoulders. It’s a great deal of information for a beginner and often leads to paralysis by analysis. Many beginning tennis players also become overanxious and over-aroused. Often the highly anxious player can’t make changes in an awkward stroke no matter what the teaching pro says. Why? The player may be holding the racquet too tightly and is only able to tune in to one simple cue: the act of hitting the ball. Other relevant cues involving swinging the racquet correctly are dropped as the player narrowly focuses. As a player progresses, learning becomes automatic and the relevant cues for a beginner dissipate. The advanced player no longer needs cues that focus on mechanics. Rather they play the shots automatically and can instead, focus on tactical plays and court awareness. As implied, many advanced warriors still utilize internal cues focused on ball striking. For them, tennis is about ball striking and less attentional focus is on tactics. As a contrast in playing styles and attentional focus, take the case of Monica Seles and Roger Federer. Monica is definitely a warrior. She focuses on almost pure offense and bludgeoning her opponent. The famous coach, Vic Braden, noted that Monica is a player in her own class in that more than any other player, she reproduces the same stroke again and again. She rarely varies her technique but uses footwork to get herself into the exact position she wants to strike the ball from. Her game is very focused on consistent ball striking which makes her an ultimate warrior. Consistent with this classification, Monica is famous for her grunting. In contrast, many experts have pointed out that Roger Federer has an incredible number of different forehand techniques – as many as 26. He isn’t focused on one particular hitting technique but constantly shifting gears from defense to neutral to offense. When he gets beaten, I think his forehand breaks down more dramatically than his backhand. If you see him when he is off, his forehand may sail as much as ten feet out. Federer is the supreme zen master. Returning back to Table 2, we now see that arousal (G), post-point response (H), attentional focus (I), and court awareness (J) are all related. It seems only natural that the all-court player or serve-and-volleyer should develop better court awareness than the baseliner. Simply the reliance on shorter points, specialty shots (e.g., the drop volley) and the ability to stay calm and focused demands greater court awareness. The counterpuncher needs the least court awareness since his main goal is to hustle down every ball. Shot-making is secondary and done only in response to the opponent. Physical Training Most experts recommend guideline base training at about a 3:1 work:rest ratio. Some researchers (e.g., Mendez-Villanueva, Fernandez, et al) have recently suggested that court surfaces, playing styles, and even serving/receiving modalities be considered in training. Blood lactate concentrations (e.g., blood lactate increases with effort) and perceived exertion (i.e., how much you feel you are exerting) were measured and found among touring pros to be different even when serving or receiving! For example, some researchers in Spain found that female elite tennis players have an average heart rate of 166 bpm on the serve but only 156 bpm on the return. We often put more effort into our serve and offensive plan. I remember coaching in one match where the two females had at least a half-dozen rallies of more than fifty strokes, up to possibly over one hundred strokes. Naturally the better counterpuncher won (and the other female, who I coached, was really a finesse all-court player who couldn’t hurt the counterpuncher enough). Serve-and-volleyers typically play the shortest points.

A good comparison is that of Rafael Nadal and Roger Federer. Now at #1, Nadal’s body can’t take the long seasonal stress of high volume of matches. He looks like he is working hard on the court. Federer on the other hand tends to look smooth and effortless. Many experts feel that Federer’s body will hold up well into his early 30s. Bjorn Borg and Mats Wilander feel that for Federer to beat Nadal, he must become more warrior-like. That means Roger needs to lift weights, hit heavier balls, and learn to trade shot for shot with Rafa. But it is not in Roger’s nature. Warriors tend to thrive on the physical battles and long rallies. Most baseline warriors almost exclusively rely on lateral movement. All-court players and serve-and-volleyers incorporate a larger share of forward movement. If you are a warrior, you often need to focus on lateral movement training. Because you might do more running and hit more groundstrokes (like Gilles Simon), you may need to focus a great deal on strengthening and training the lower body to take repeated punishment. You may want to train with lateral sprints at 1:1, 1:2 and 1:3 work:rest ratios. Although lateral movement is emphasized, the warrior should also adapt to a good number of directional changes and agility. Directional changes and deceleration are major stressors of the lower body and are major factors in injuries. A zen master who plays an all-court game, however, may train at 1:2, 1:3 and 1:4 work:rest ratios. Their springs should include slightly more different types of movement including forward movement. At the very least, try this experiment with a friend. Have your friend take a stop watch to your match. Have her record the time you actually start playing (from the first service point) to the end of the match. Then, have her use to the stop watch to record the time you actually are playing points. It is best to record the length of the points on a piece of paper. For example, the points might last 4, 10, 2, 7, and 8 seconds in the first game which lasted 3:10. Chances are that most of your movement will be lateral if you are a baseliner. Make sure your opponent is typical rather than the rare serve-and-volleyer or the pusher counterpuncher. That ensures your play:rest ratio is typical. If you play doubles, have your friend measure the play:rest ratio also. But have her track your footwork as well. You will have considerably more forward and stretch movements. Doubles movement can be significantly different from singles movement. Good doubles players should have a zen master approach where a variety of shots and court awareness are more important than grinding out points at the baseline. Tailor Your Game and Training To summarize, we have seen the relationship between personality, arousal, playing style, and training. The model I presented is idealized so it may not work exactly but can help you understand a bit more about tailoring your game and training. If you believe in consistency and have foot speed, then you may thrive as a warrior, particularly a counterpuncher. If you are impatient and have power, you may thrive as a warrior, particularly an aggressive baseliner. If you like to create points and have a calm personality, you are best as a zen master. Only some people fall into specific category or stereotypes. So everyone needs to work on a little of everything. But consider the time you spend on your game. Unless you are a junior in a serious academy or playing college tennis, typically you won’t have more than 4-5 hours per week to work on your game. Identify your strengths first. Build your game around your strengths. Be efficient about what you need to work on.

If you have a 3.0 rating or less, split your time between serving/receiving, baseline play, and inside-the-baseline play evenly when working with your teaching pro. You want to continue developing all facets of your game. Even though in match play you may hit more groundstrokes, don’t necessarily choose that to work on with your teaching pro since you probably hit plenty of groundstrokes when hitting with friends. In fact, what separates experts from non-experts in sports is how they practice. Non-experts may spend the same time practicing, but it is not as effective since they a) pick things they are already comfortable with, b) don’t challenge themselves with new things, or c) don’t put in the same effort or intensity. Always challenge yourself at every practice session. Ask your teaching pro to add something new for a few minutes each time. Your technical development is your best path to improvement. Fitness training can be important if you lack average athleticism. At the 3.5-4.0 level, you probably have a couple strengths like a very good forehand or a strong serve. Keep refining your strengths but spend about 1/3 of your time picking areas of weakness. Your opponents have enough skills to pick on your weakness. So if you have a weak backhand, work with your coach to improve it. At the 4.5 and higher level, fitness training becomes more important. Most of your time on-court is refinement but to maximize your performance, you need relatively good fitness or a combination of weapons and great tactical and court awareness. Work on using your weapons in patterns of play. For example, if you have a great forehand, you want to develop patterns around your inside-out and inside-in forehand. Fitness can make the forehand more effective since you can run around more backhands. Deliberate, structured practice becomes very important for improvement. Keep challenging your game in different ways. Research (K. Anders Ericsson) shows that at this level, particularly, the most successful athletes are more open-minded and will find new ways to challenge themselves and incorporate deliberate practices better than less successful athletes. Whether you are a warrior, zen master or something else, it is important to find compatibility with your personality, mentality, and physical game. Whether you choose to focus on running down every ball or creating points by using your court awareness, you can use this information to understand the mental-physical connection in tennis. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug Eng's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug Eng EdD PhD coaches men's tennis at Tufts University. During the summer, he directs at the Tennis Academy at Harvard. He has received four divisional Pro of the Year honors from the PTR and USPTA and several national awards including PTR Tester of the Year. Doug is a member of the USTA National Sport Science Committee. He completed the USTA High Performance Coaches program and frequently runs educational and training programs for coaches. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||