|

TennisOne Lessons How America Can Produce Tennis Champions Again Paul Fein The decline of American tennis has been debated with insight and passion for the past decade. USTA leaders, former and current world-class players, tournament directors, coaches, teaching pros, and the media have weighed in on what we’re doing right and what we’re doing wrong. We do have promising young players, particularly among the women, such as Australian Open semifinalist Madison Keys, Sloane Stephens, CoCo Vandeweghe, Taylor Townsend, and Victoria Duval. The men are another story, a discouraging one. Our last Grand Slam singles champion was Andy Roddick, way back at the 2003 US Open. We haven’t won the Davis Cup since 2007. We haven’t even had a quarterfinalist at the Australian Open since 2010, at the French Open since 2003, at Wimbledon since 2009 (when Roddick reached the final), or at the US Open since 2011. Our two highest-ranked players are 29-year-old John Isner at No. 20 and 27-year-old Sam Querrey at No. 43. Jack Sock, a big-hitting 22-year-old ranked No. 58, has top-10 potential if he gets in superb physical condition. Bob and Mike Bryan, the greatest men’s doubles team in history, still rank No. 1, but they’ll be 37 on April 29. It’s too soon to panic, but the time is always right to reconsider past approaches and consider new ones. Here are five proposals that can help America produce champions again and perhaps even regain our place as the No. 1 tennis nation in the world. Go Two-Handed or Go Home One-handed backhands can look elegant, especially those stroked by Roger Federer and Justine Henin. But tellingly, both superstars rate their forehands as much better shots. At all levels of tournament play, however, the best two-handed backhands are clearly superior to the best one-handed backhands. Why? Two-handed backhands handle power and generate power far more effectively. Although Stan Wawrinka, nicknamed “Stanimal” for his tremendous strength, sometimes blasts powerful one-handed backhands, even he needs a long backswing to produce that power. Federer, Grigor Dimitrov, Ivo Karlovic, and Fernando Lopez run around to avoid hitting their weak, vulnerable one-handed backhands as much as to try to hit more aggressive inside-out and inside-in forehands. Two-handed backhanders, such as Novak Djokovic and Andy Murray, also run around, but they aren’t compelled to. Furthermore, Wawrinka’s backhand return of serve is sliced, blocked, or stroked no faster than medium-speed; overall, it’s inferior to most two-handed returners on the ATP tour. Because both hands stay on the racket, the two-handed backhand is more grooved, controlled, and consistent. The great two-handers, such as Djokovic, Andre Agassi, Marat Safin, Maria Sharapova, Simona Halep, Lindsay Davenport, Jennifer Capriati, and Li Na, are solid as a rock. It’s no accident that they all use semi-closed (a line drawn from the toes of their shoes goes leftward at a 45-degree angle) or occasionally closed stances, rather than square or open stances—except when they run out of time. That gives them better balance and stability and enables them to hit through the ball solidly without the mishits that are much more common with open-stance backhands. Almost all two-handed players can also slice one-handed backhands. The most skilled and smartest two-handers use the slice to absorb the pace of big serves and groundstrokes, to play defense when outstretched in groundstroke rallies, to keep approach shots low, and to break their opponent’s timing and rhythm during rallies. In short, two-handers have the best of both worlds. In sharp contrast, one-handed backhand players can’t hit two-handed backhands.

As Aldous Huxley famously said, “Facts do not cease to exist because they are ignored.” The facts are that in the year-end 2014 WTA rankings 97 of the top-100 players had a two-handed backhand, including every top-15 player. Twenty-five ATP players in the top 100 used one-handed backhands; but that number will surely decline because the vast majority of one-handers are in their late 20s or 30s. By 2025, the one-handed (only) backhand will likely become extinct among world-class players. Ironically, Mats Wilander, one of the few remaining diehard defenders of the one-hander, boasted an excellent two-handed backhand, without which he would not have won seven Grand Slam singles titles. “[Grigor] Dimitrov is going to be crucial for the one-handed backhand, of course,” Wilander, who is based in Idaho now and teaches youngsters around the country with his Wilander on Wheels program, told Fairfax Media. “We’ve got to start letting kids play the way they want to play.” Dimitrov’s backhand continues to be a glaring weakness. But the overriding point is that kids aspiring to become champions should not “play the way they want to play.” They should be taught the strokes and tactics that give them the best chance to achieve their dreams. In this case, the two-handed backhand is mandatory. Get Fit or Get Whipped Observers with diverse backgrounds, such as former USTA Player Development General Manager Patrick McEnroe, 1980s star Hana Mandlikova, USTA Director of Coaching Jose Higueras, and USTA president Katrina Adams, have rightly blamed our decline partly on players who are lazy, spoiled, and unfit. “When a high percentage of the coaches want it more than the players, we have a problem,” rued Higueras. “There is a lack of motivation among our young people,” Adams told Tennis magazine. We need ambitious, hungry young players who not only like to compete hard, but equally important, are willing to train hard. Rising Spanish star Garbiñe Muguruza, sounding like Rafael Nadal, told Tennis Channel: “I work hard, and I have to continue suffering [italics added] if I want to be up in the rankings.” The lean Muguruza, who thrashed Serena Williams 6-2, 6-2 at the 2014 French Open, works out 9 to 11 sessions a week, totaling 12 to 17 hours, with her fitness trainer, Ignasi De La Rosa.

Contrast Muguruza’s philosophy with what obese Zina Garrison, the 1990 Wimbledon finalist, told 18-year-old Townsend, her highly talented, but very overweight, pupil: “This is your body, this will be [italics added] your body, embrace it.” Regrettably, too many American pros this century have failed to reach their potential because they were overweight. Mardy Fish was 25 pounds overweight and didn’t lose it and get into tip-top shape until he was 28. Late in his career, Andy Roddick dropped 15 pounds to return to 192 pounds, his weight when he won the 2003 US Open and set the serve speed record in 2004. Early in their careers, Davenport, Vandeweghe, and Sock were overweight. Taylor Dent was much too heavy, and last year Isner and Ryan Harrison dropped eight pounds. It’s no accident Isner won only two of his last 13 five-set matches, including his recent Davis Cup marathon with British underdog James Ward. Unlike 6’10” NBA players (even considering they get subbed and have halftimes to rest), he gets too tired way too soon. So Job One for some American players is simply to find out what their ideal weight is and then get it and keep it, even during the off-season. As 1987 Wimbledon champion Pat Cash asserted in The Times (UK), “One undeniable fact over the foreseeable tennis future is that no quality will be more important in the shaping of champions than durability and fitness.” While Job One is necessary, it’s far from sufficient. Roger Federer, when asked what the recipe is for producing great American players, advised: “Most important is the work ethic and that the kids understand that it’s not the coach’s job to motivate them, or that if you win a junior tournament you’re actually great. . . . I left home at 14, stopped school at 16, and went on tour. I had a hard time understanding what hard work was, but eventually I figured it out. Early enough. That’s the key. If the kids don’t understand and don’t want to put in the hard work, they’ll never get anywhere.” Heed the Need for Speed "Speed is the biggest need for our players," asserted former speedster and world No. 5 Jimmy Arias, now a respected analyst for Tennis Channel. "The fastest and best athletes in America are lured to more glamorous sports—football, basketball and baseball. Our top juniors are big servers, but they will not catapult us to dominance because they don't have the speed to stay two feet behind the baseline and take the ball early." With rare exceptions, such as Davenport, tennis champions are very fast. And those not blessed with terrific speed, such as Helen Wills Moody, Chris Evert, Martina Hingis, and Agassi, position themselves and anticipate extremely well. Since today’s shots whiz by faster than ever, players must run faster, too. So it’s not surprising that Murray improved his speed, strength, and stamina under the guidance of track superstar Michael Johnson, the former world record-holder in the 200 meters. The hugely successful Russian tennis program emphasizes improving speed from the start, for their 7 to 10-year-old players.

E. Paul Roetert, Ph.D., former USTA Managing Director of Player Development, reported that its program also focused very early on speed as well as agility because tennis requires movement in all directions. Many of the USTA conditioning drills are conducted with racket in hand and the proper work/rest ratio in mind. The USTA has worked with a number of experts, including Don Chu, Mark Grabow, and Gary Brittenham, over the years, and more recently has hired its own conditioning and strength coaches. The 1998 book, Biology of Sport, written by A. Viru, J. Loko, A. Volver, L. Laaneots, K. Karlesom and M. Viru, identified two windows of trainability as potential periods for accelerated adaptations to speed training. They are 6 to 8 years of age and 11 to 13 years of age for males and 7 to 9 years of age and 13 to 16 years of age for females. The USTA High Performance program has followed those age guidelines. The key to training for speed, advised Dr. Roetert, a member of the United States Professional Tennis Association’s Player Development Advisory Council, is to make it as tennis-specific as possible. Coaches should focus on making this part of the day-to-day training, involving patterns that are multi-directional and drills that include holding the racket as much as possible. In his 2014 book, The Secrets of Spanish Tennis, Chris Lewit asserted, “In Spain, the footwork is taught in 360-degree movements, rather than just laterally or forward. In my experience, most American coaches teach 180-degree movement—lateral and forward—to attack.” Is your coaching focusing regularly and intensively enough on running drills as well as the full panoply of directional patterns, including diagonal and retreating patterns? Play on Grass and Clay If you can excel on either grass or clay, you can almost always play at least reasonably well on hard courts. But if you excel on hard courts, particularly if you’re an American man, you often play mediocre or poor tennis on clay or grass or both. Sadly, that’s been the case for America’s “hard-court specialists” for a decade. Let’s look at the record. No American man has captured the French Open since Agassi in 1999, and none has even reached the quarterfinals since Agassi in 2003. Andy Roddick, the 2003 US Open champion, had a career 9-10 record at Roland Garros, though he did fare well at Wimbledon, reaching three finals. Roddick was the exception, however. Former world No. 4 James Blake wound up 6-7 at Roland Garros and an equally dismal 7-9 at Wimbledon. Former No. 7 Mardy Fish was only 4-6 at Roland Garros and 15-10 at Wimbledon. Isner, who reached a career-high No. 9, is also spinning his wheels, going just 8-6 at Roland Garros and 5-6 at Wimbledon, despite his rocket serve. Querrey, who reached a career-high No. 17, is 4-8 and 7-7.

Our women are not exactly setting the world on fire either on clay and grass. Since 2007, only Serena Williams, the 2013 champion, has advanced to the quarterfinals at Roland Garros. Since 2006, aside from Serena, 33, and her sister Venus, 34, only Sloane Stephens, in 2013, has reached the quarterfinals at Wimbledon. How can this embarrassing failure be reversed? To improve their stroke as well as positional and tactical shortcomings, young American prospects should learn the sport chiefly on clay and grass courts. Why? These specialty surfaces require special skills. Therefore, learning on clay and grass can best help juniors develop into clever, skillful, durable, tenacious, and versatile players on all surfaces. On grass, that stroke and footwork versatility entails mastering volleys, half-volleys, overheads, approach shots, and in the best-case scenario, the art of serving and volleying. On clay, that stroke and footwork versatility includes mastering drop shots, drop volleys, angles, change of pace and spin, and the skills to handle those shots from opponents. Therefore, I recommend that our talented juniors both train and compete half the time on clay and a third of the time on grass, with hard courts (and indoor carpet) allotted the least time. If they can master clay and/or grass, then proficiency on hard courts—with its true bounce and medium speed—will come easily, but it seldom works the other way around. We know that from analyzing the aforementioned results. Less play on hard courts, an unforgiving surface that punishes the body, will also decrease injuries. Shockingly, none of the three USTA national training centers has grass courts. What’s even more shocking is that none of the 106 courts will be grass at the USTA’s new $60 million state-of-the-art training facility in Lake Nona, Florida. How can our players win Wimbledon if they can’t even practice on grass? The Quest for the Best Athletes As U.S. Davis Cup captain and perspicacious TV analyst, Jim Courier is keenly aware of the shortage of truly gifted athletes in American tennis, particularly men’s tennis. “It’s not the same story as a kid finding a soccer ball and becoming Maradona or Pelé,” former world No. 1 Courier told The New York Times. “It’s much more complicated than that. You can’t play tennis without significant resources whether it’s from a federation, a friend, a scholarship or a family. I’m very analytical about it, but also resigned to the fact we need luck and great athletes, and the fact that tennis is not a first-tier sport in America does not make it any easier.” A multitude of USTA school and inner-city programs, and other initiatives such as the Ashe-Bollettieri Minority Project, are designed to attract minorities and disadvantaged youngsters. However, the athletic crème de la crème rarely make tennis their favorite sport—if they even try tennis at all. That may change gradually if the USTA succeeds with its new program to attract the fast-growing Hispanic community to tennis, or if McEnroe does with the Johnny Mac Tennis Project in New York City. If the best black athletes in the U.S. aren’t choosing tennis, some of the best black athletes elsewhere likely would, if given the opportunity. Just as the Boston Red Sox recruit, sign, and train terrific black athletes from the Dominican Republic and Cuba, we can adopt the same strategy in West and Central Africa where super athletes abound. Besides Arthur Ashe, the only black man to win a Grand Slam singles title was Yannick Noah. Ashe discovered the talented 11-year-old in Yaounde, Cameroon, in 1971 and had him sent to France for advanced training. Twelve years later Noah captured the French Open to become a hero in both nations. In 2000, Togo’s Komlavi Loglo reached the Orange Bowl boys’ 16 doubles final with Algeria’s Lamine Ouahab. The muscular 6’, 168-pound Loglo epitomized the physically superior West African athlete. In track Loglo ranked as the fastest 14-year-old in Africa in the 100-, 200-, and 400-meter races. “Everybody in Togo is a good athlete,” Loglo told me then. “I’m 100 percent sure I can be the next tennis champion from Africa. I can be No. 1 in both singles and doubles.” That never happened, of course. You’ve likely never even heard of Komlavi Loglo because sub-Saharan Africa, aside from the Republic of South Africa, still lacks sufficient funding, courts, and topnotch coaches to develop their most promising boys and girls. Loglo peaked at only No. 316 in singles and No. 235 in doubles. Now at age 30, he coaches in Barcelona, Spain, and plays the club tennis circuit in Europe for a few hundred Euros a weekend. “If I had enough money to play 30, 40 tournaments a year, instead of 15, I would have been [ranked in the] top 50, for sure,” he told me recently. “I definitely had a chance to be top 10. [Then] I was better than [former No. 5 Jo-Wilfried] Tsonga and other guys who made the top 30.” But what if scores of super-athletes like Loglo from Togo, Cameroon, Nigeria, Ivory Coast, Ghana, Congo, Senegal, and the Democratic Republic of Congo are brought to the United States and are trained here when they are 10 to 14 years old? “Of course, it would be great for us,” enthused Loglo. “There are a lot of really talented and eager young players who just need the right training and funding to become great players.” This is a win-win scenario for African athletes and for American tennis. It has the potential to change the future of tennis.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Paul Fein's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Paul Fein Paul Fein has received more than 30 writing awards and authored three books, Tennis Confidential: Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies, You Can Quote Me on That: Greatest Tennis Quips, Insights, and Zingers, and Tennis Confidential II: More of Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies. Fein is also a USPTA-certified teaching pro and coach with a Pro-1 rating, former director of the Springfield (Mass.) Satellite Tournament, a former top 10-ranked men’s open New England tournament player, and currently a No. 1-ranked Super Senior player in New England. |

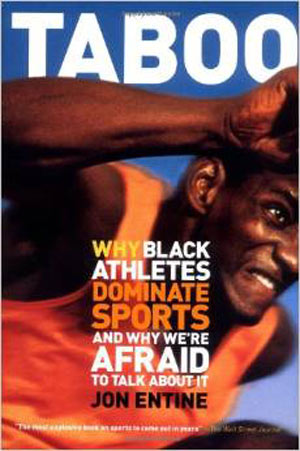

Who are the best athletes with the physical attributes—explosive speed, strength, agility, and jumping ability—most necessary for world-class tennis? Answer: African-Americans. “Obviously blacks have walked into basketball, baseball, and football, and they are tremendous athletes,” noted former superstar John McEnroe in 1990. “If tennis is anything like the other sports, whites won’t be able to compete with them.” Those who disagree with McEnroe should read the well-researched and -reasoned book, Taboo: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We’re Afraid to Talk About It.

Who are the best athletes with the physical attributes—explosive speed, strength, agility, and jumping ability—most necessary for world-class tennis? Answer: African-Americans. “Obviously blacks have walked into basketball, baseball, and football, and they are tremendous athletes,” noted former superstar John McEnroe in 1990. “If tennis is anything like the other sports, whites won’t be able to compete with them.” Those who disagree with McEnroe should read the well-researched and -reasoned book, Taboo: Why Black Athletes Dominate Sports and Why We’re Afraid to Talk About It.