|

TennisOne Lessons Should Nadal Be Seeded No. 1 at the French Open? Paul Fein “No problem can withstand the assault of sustained thinking.” — Voltaire The first recorded reference to seedings appeared in 1898 when American Lawn Tennis magazine wrote: “Several years ago, it was decided to ‘seed’ the best players through the championship draw in handicap tournaments so that the players in each class shall be separated as far as possible one from another.” How ironic that 125 years later our sometimes confused, fractious sport still hasn’t sensibly implemented what our 19th century pioneers invented and explained perceptively. Seeding controversies have raged periodically, usually about whether seedings should be based strictly on rankings, or whether to take into account players’ records on a particular court surface. One of the most clear-cut and potentially precedent-setting cases currently involves Rafael Nadal, who is widely considered the greatest clay court player in men’s tennis history. Nadal has won a record seven titles at Roland Garros, the only Grand Slam event on clay. The 26-year-old Spaniard also has amassed a record 19 ATP World Tour Masters 1000 clay titles, as well as 17 other lesser clay titles. His near-total clay domination is further evidenced by a .931 won-lost percentage (285-21), yet another Open Era career record, and an even more astounding .959 (258-11) since 2005.

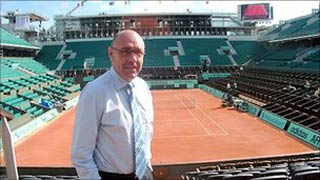

One would think those near-perfect credentials, plus his status as the defending champion, would ensure that the French Open committee would have seeded Nadal No. 1, or at least No. 2, when the tournament starts May 26. Yet that won’t happen for two reasons. First, Nadal is ranked a surprisingly low No. 4, due to a seven-month injury layoff when he could not accumulate ranking points. Second, Roland Garros has weathered past criticism for its flawed seedings, but it has never deviated from the ATP and WTA rankings. With the pressure building this year because of The Nadal Problem, its leaders missed another opportunity to do the right thing. On May 4, when Nadal was ranked No. 5, tournament director Gilbert Ysern announced Nadal would not be protected with a higher seeding. “Considering what Nadal represents in Paris, i.e., the best player in the tournament’s history, it seemed incongruous that he arrives in Paris with the number 4 or 5 seed,” Ysern told French sports daily L’Equipe. “But it was said to be fiddling. What was supposed to be a strong symbol, a tribute, was seen as messy business.”

Yes, this seeding is certainly incongruous with the irrefutable principle that the best players be separated as far as possible from one another in the draw. Ironically, Ysern expounded this very principle in 2000. Representing the French tennis federation and working as a consultant with the ATP, he developed a computer program for seedings that was “surface specific” for Grand Slam seedings. Ysern’s program used a player’s performance on clay, grass, indoors, or hard court, as well as his performance at a given Grand Slam tournament in past years and recent results. What Ysern lacks now is not expertise or experience, but apparently either the courage to fight for his long-held convictions or the ability to change the antediluvian thinking of his Roland Garros colleagues. So, with Nadal seeded No. 3, after Andy Murray withdrew May 21 because of a chronic back injury, and Djokovic No. 1, a rematch between the world's two best clay courters, who treated us to a thrilling 2012 final, could happen prematurely in the semifinals. If Nadal hadn't retained his title in Rome last week and Murray hadn't pulled out, Nadal and Djokovic could have met even more incongruously in the quarterfinals. With that in mind, let’s analyze this controversy using pertinent criteria to determine what can—and should—be done to protect the players and the tournament. History and Rationale of Seedings From 1919 to 1925, the battles at the U.S. Nationals (now the US Open) between imperious “Big Bill” Tilden and gentlemanly “Little Bill” Johnston enthralled the sporting public. The galleries invariably rooted for Johnston, the 1919 champion, but were thereafter disappointed when the more powerful Tilden prevailed. The 1920 Tilden-Johnston final produced “five of the most terrific sets ever staged on a turf court,” according to former star Richard Larned. In 1921, however, their eagerly anticipated showdown proved something of a letdown through no fault of their own.

“The old non-seeding system left matters entirely to chance,” recounted Parke Cummings in American Tennis: The Story of a Game and Its People. “The result was that luck placed Tilden against Johnston early in the 1921 tournament, with Tilden the winner. Fans and officials alike seemed to feel that this was like having Macbeth fight Macduff in Act II instead of Act V. The rules committee forthwith struck a telling blow against the anti-climax, and thereafter all tournaments were seeded. Tilden and Johnston were again ringing down the curtain.” Wimbledon soon heeded the American lesson, not wanting its best players to eliminate each other early in the tournament. “1924 marked the beginning of an extraordinary run of French ascendancy that coincided with the introduction of a modified form of seeding,” wrote the distinguished British journalist John Barrett in 100 Wimbledon Championships: A Celebration. “It was decided that nations could nominate up to four players who would be drawn in separate quarters. This was of singular benefit to Rene Lacoste, Henri Cochet, Jean Borotra, and Jacques ‘Toto’ Brugnon, the doubles’ expert among the ‘Four Musketeers,’ as this talented quartet inevitably became known.” Seedings were introduced at Roland Garros in 1925, the first year entries were accepted from other countries. The Australian Championships adopted seedings for men in 1925 and for women the following year. Starting in 1927, Wimbledon completely seeded its gentlemen’s and ladies’ singles events with seeding numbers given to the top eight players. The U.S. Nationals, presumably to attract faraway players at a time when overseas transportation was by slow boat, instituted foreign seedings (in addition to U.S. seedings), also in 1927. As few as two and as many as ten foreigners were seeded, with eight the most common number, until the foreign seedings were discontinued in 1955. Historically, seedings were rightly intended for two compelling reasons: to spread the top players as much as possible in the draw so they cannot meet (assuming they keep winning) until as late as possible during the tournament, and also to give the draw the most permissible balance. Put differently, seedings recognize and reward superior tournament results. Past Controversies Disputes about seedings were rare before the Open Era (starting in1968), chiefly because pride and glory, rather than prize money, were at stake. Easy-going Australian Fred Stolle was irked, though, when the 1966 U.S. Championships seedings included Americans Dennis Ralston, Clark Graebner, and Cliff Richey, but not him. “I did not appreciate the snub and took the whole matter rather personally,” he recalled in his memoir Tennis Down Under. “My dander was up and I went into the tournament very motivated to make a good showing and prove a point.” Stolle sure did, as he knocked off Graebner, Richey, his old nemesis Roy Emerson, and young star John Newcombe to capture the title.

Seedings were somewhat subjective then. The Forest Hills seeding committee apparently put more emphasis on Stolle’s second round loss at Wimbledon two months earlier than on his winning the German Championships, and reaching the French and Italian quarterfinals, as well as his past runner-up performances at Wimbledon (1963−65), the Australian Championships (1964−65), and the U.S. Championships (1964). When the ATP and WTA created computer ranking systems in 1973 and 1975, respectively, all their Tour events used those rankings for seedings. However, the Grand Slam rule states: “The selection and arrangement of seeds is at the discretion of each Grand Slam tournament.” Wimbledon sowed the seeds of dissent in 1975 when it unjustifiably awarded the second seed to 1974 finalist Ken Rosewall, who had skipped the Australian and French Opens and almost every significant tournament during the previous nine months. Six years later, the WTA was furious when Wimbledon boosted No. 5-ranked Hana Mandlikova, winner at Roland Garros two weeks earlier, to No. 2 in the seedings. An outright seedings scandal besmirched the 1996 US Open. The United States Tennis Association, for the first time in 116 years, conducted the traditionally public men’s draw in secret, prompting suspicion that it was hiding something. Indeed it was: the USTA had reversed the normal procedure by placing the 112 non-seeded players in their slots before assigning the order of the 16 previously announced seeds. Thus “the luck of the draw”—a time-honored concept denoting the random selection of players’ names—was replaced by serious questions about whether America’s seeded players were randomly placed, or favorably put against easier early-round opponents. The web of perceived (or actual) favoritism grew more tangled when the US Open seeding deviated from the ATP’s official computerized rankings for the first time since they were created. The most controversial changes moved No. 8-ranked Andre Agassi, a crowd-pleaser and finalist the previous year, up to sixth seed which guaranteed he wouldn’t meet top-seeded Pete Sampras before the semifinals. They gave No. 3-ranked Michael Chang, instead of No. 2 Thomas Muster, the second seed, and positioned Chang on the other half of the draw from Sampras; and demoted French Open champion and No. 4-ranked Yevgeny Kafelnikov to the seventh seed.

Player Outrage Players, American and foreign alike, were outraged. “It’s like cheating,” charged Austria’s Muster. “It would be like fixing a football, basketball or NHL game,” insisted Ukraine’s Andrei Medvedev. “How can it be? I’m No. 4 in the world. I earned it,” objected a shocked Kafelnikov, a Russian who withdrew in protest. To try to untangle its growing web of manipulation and to placate players, like Germany’s Michael Stich who threatened to boycott the tournament, the embarrassed USTA, in yet another unprecedented move, made the draw again—although the dubious seedings stayed intact. Criticizing the USTA for trying to create what it called its “predicted order of finish,” Mark Miles, CEO of the ATP Tour, rightly said the USTA had “caused speculation about its motives … commercialism, a desire for what some have called a telegenic final, and nationalism.” (Tennis magazine charged, “When Snyder allowed CBS [television] to dictate seedings and potential matchups, he took the sport to a level very close to professional wrestling.”) The seedings were “completely justifiable” claimed USTA president Lester Snyder. “Really, seeding a tournament is a matter of how you predict people are going to finish. You want to seed the players as accurately as you can to get the best possible finish you can get,” he asserted. The first half of Snyder’s assertion was completely wrong because seedings are not intended as—and should not be considered as—predictors of future performance. A corollary of that is that seeding committees are never “proven right” or “proven wrong” depending on how given seeds or non-seeds fare at their tournament. If you’re looking for predictions about how certain players will fare, consult your local bookmaker for odds. The US Open has no business changing the seedings except in two circumstances. It should use its discretion when a star returns after a prolonged layoff due to injury or accident. In 1995, the US Open correctly decided to seed former Monica Seles second (although a somewhat lower seeding would also have been justified) when the former world No. 1 returned from a 27-month absence after being stabbed by a crazed spectator during a Hamburg match. In sharp contrast, the 2011 US Open blundered when it seeded Serena Williams a lowly 28th after returning from a serious illness, and Serena had to face and defeat No. 4 Victoria Azarenka in the third round. Another exception would be to upgrade the seeding of a bona-fide hard court specialist whose hard court record is both extensive and far better than his ranking. Such specialists are rare, though, because Flushing Meadows’ medium-speed Deco Turf II hard courts don’t favor any particular playing style, other than the all-court game. The French Disconnection Ruckuses over rankings have long rankled clay court standouts who feel victimized at Wimbledon but find no seeding reciprocity at Roland Garros. The fiery Muster wound up with a horrendous 0-4 career record at Wimbledon. Yet, he was still angered about his No. 7 seeding in 1996—despite his No. 2 ranking—before withdrawing because of a thigh injury. Britain’s John Lloyd fairly commented, “I think Muster was lucky to be seeded at all. He doesn’t have any record at all on grass—I don’t care whether he’s the French Open champion or whatever. If certain players are specializing on clay, then seed them for clay. And if players are specializing on grass, then seed them for that.” At the 2000 Wimbledon, five grass-court standouts—Tim Henman, Mark Philippoussis, Richard Krajicek, Pat Rafter, and Greg Rusedski—gained seedings higher than their rankings among the top 16 seeded players. Their gain, though, came at the expense of clay courts standouts Alex Corretja and Albert Costa. In a USA Today column, Martina Navratilova, who won a record nine Wimbledon singles titles, criticized Spanish “refuseniks” No. 11 Corretja and No. 15 Costa, who pulled out of Wimbledon after being unseeded in the draw. “The men’s seedings should be adjusted at the French Open, just like they are here, for players who aren’t as good on clay,” rightly argued Navratilova. “That doesn’t excuse the Spaniards for pulling out of Wimbledon. Their point is that the ATP makes them play Wimbledon, but doesn’t support them with the seedings. The Spaniards have a valid point. They don’t adjust the seedings at the French, and they really should do it if they’re going to do it here.”

In the early 1980s, the World Championship Tennis (WCT) tour ranked pros according to their results on four different surfaces: grass, clay, hard, and indoors. That’s not feasible or sensible today. Thirty years ago, tennis was blessed with four distinctly different playing styles—serve and volleyers, hard-hitting baseliners, light-hitting but strategic pushers and retrievers, and versatile all-court players. Now styles have become homogenized with powerful baseliners the prevailing trend. That stylistic convergence parallels a convergence in court speeds as a switch to 100% rye grass at Wimbledon has slowed their courts and reduced the odds for net-rushers. Also, faster balls at Roland Garros have rewarded backcourt aggression more than ever. In lieu of different rankings for different surfaces, it’s easy to understand why not only clay court standouts, but also fans and TV networks, should have objected when Andy Roddick, who compiled an abysmal 9-10 career record at Roland Garros, was seeded there at all. Their most egregious mistakes were his No. 2 seeding in 2004 and 2005. A decade earlier, when Sampras ranked No. 1 for six straight years (1993−98), his reasonably good French Open record (highlighted by reaching a semifinal and two quarterfinals) deserved a seeding but certainly not No. 1. Former world No. 1s Gustavo Kuerten (career 7-5 Wimbledon record), Carlos Moya (7-8), Marcelo Rios (3-3), and Muster, plus two-time French champion Sergi Bruguera (4-4), never merited a top 8 seeding or arguably even a top 16 seeding at the Big W. But what’s good for the clay goose is good for the grass gander. Grass-court stars Newcombe, Arthur Ashe, and even John McEnroe (late in his career) should have been demoted in the French seedings. The Case for Rafa In April, a debate on this controversy on SI.com posed the question, “Should the French Open adopt Wimbledon’s policy to allow for subjective seeding to boost Rafael Nadal’s seed?”

However, the question’s premise is wrong because the All England Club uses an objective formula for the men’s seedings, one similar to Ysern’s model. This formula takes into account ATP points and grass-court points from the previous 12 months, plus 75% of grass-court points from the 12 months before that. This sample, though valid, is relatively small this year, comprising only three weeks and five tournaments for men compared to 15 weeks and 22 tournaments on clay. (Wimbledon will start a week later in 2015 to lengthen the grass-court season and give players more time to recover from the French Open.) As Barrett averred recently, “Our present system for men at Wimbledon has worked very well since we introduced it in 2001. This system distributes players fairly throughout the draw, based on their current form and their past record on grass, so that the public, the tournament and the players themselves all benefit. The French have indeed shot themselves in the foot this time. We should all campaign for objective seedings at all four Grand Slam Championships.” Furthermore, the premise that pro rankings are sacrosanct in the first place is neither valid nor justified. In fact, both the ATP and WTA rankings are seriously flawed because they throw out players’ worst results from some tournaments. Also, the WTA rankings wrongly award the Olympics gold medalist an absurdly low 685 points compared to 2,000 points for champions at the four Grand Slam events. Finally, while “bad cases make bad laws” in the legal profession, this case is as clear-cut and optimal as one could hope for two powerful reasons: Nadal’s extraordinary career record on clay is far superior to all other players. Also, his seven-month injury layoff prevented him from earning ranking points, especially from four of the biggest events—the US Open, Australian Open, London Olympics, and ATP World Tour Finals. Nadal played only 11 tournaments, much fewer than the 18 that are used to figure the rankings. All of that significantly lowered his ranking. The King of Clay deserves to be treated like a king at the French Open. It’s time for this prestigious tournament to correct the wrongheaded seeding policy it has followed since 1925. It’s too late for this year, but the controversy is far from over. Tennis doesn’t need a Supreme Court to adjudicate this simple case. Roland Garros only has to give it the “sustained thinking” that Voltaire, one of France’s greatest thinkers, advised. Then justice will have been served for the players and entertainment enhanced for the fans. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Paul Fein's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Paul Fein Paul Fein has received more than 30 writing awards and authored three books, Tennis Confidential: Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies, You Can Quote Me on That: Greatest Tennis Quips, Insights, and Zingers, and Tennis Confidential II: More of Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies. Fein is also a USPTA-certified teaching pro and coach with a Pro-1 rating, former director of the Springfield (Mass.) Satellite Tournament, a former top 10-ranked men’s open New England tournament player, and formerly a No. 1-ranked Super Senior player in New England. |