|

TennisOne Lessons Make Your Overhead a Smash Paul Fein “Okay, I’ll serve first and take the overheads.” — What Darlene Hard told Rod Laver when they walked on court to play mixed doubles together at the 1959 Wimbledon. Americans call this shot an “overhead,” while most of the rest of the world call it a “smash.” Whatever term you use, this weapon is—or should be—the most devastating one in your arsenal. From Gerald Patterson and Jean Borotra in the 1920s; Alice Marble in the 1930s; Pancho Gonzalez, Lew Hoad, Ken McGregor, and Althea Gibson in the 1950s; to Billie Jean King, Pete Sampras, Roger Federer, and Serena Williams in the Open Era; the overhead has delivered the coup de grace in spectacular fashion. No one has done it with more panache than Sampras who leaped high to smack short lobs with his famous “slam dunk” overhead.

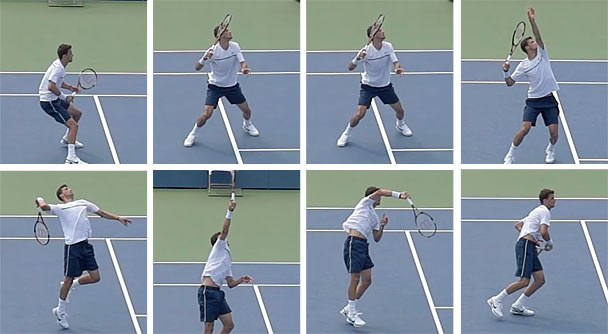

While a deadly weapon for skilled tournament players, the overhead can be a dreaded and dreadful weakness for recreational players. “If you want to play the game seriously, or if you want to play the net at all, you must be able to hit the overhead consistently,” wrote 1930s champion Fred Perry in Tennis Strokes & Strategies. “If you don’t, your opponent will lob you into submission. On the other hand, if you smash well, you will welcome those lobs eagerly. There is probably no greater satisfaction in tennis than taking a full-blooded crack at an overhead and putting it away with a resounding winner.” How right Perry is! With correct technique, positioning, and tactics, you can eagerly smash lobs with both power and consistency. Here are some tips to master the basics and fine points of the overhead. Get a Grip The Continental grip is mandatory for the overhead. It will enable you to snap your wrist to maximize power, and it will also allow you to add a bit of slice, when desirable, particularly on bounce overheads. It’s also the most practical grip. Since you’re using the Continental grip when volleying, you won’t have to change your grip at the net to smash lobs. As with the serve, you need only moderate firmness. Too tight a grip will reduce the fluency and rhythm of your swing and the effectiveness of your wrist snap. You want your arm and wrist to be loose and relaxed in order to generate plenty of power. If your grip is too loose, however, the racket will turn in your hand before or when your racket contacts the ball. That will result in a loss of both power and control. The Swing Is the Thing “It Don’t Mean A Thing If It Ain’t Got That Swing,” the title of Duke Ellington’s famous song, applies to the overhead, too. The swing is the same as that for a flat serve, except that you eliminate the initial pendulum motion. Instead, start bringing the racket back at head level when the ball is clearing the net. After you load your weight on your rear leg, let the racket drop behind your back in the backscratching position with your elbow fully bent. From there, transfer your weight forward and simply use the same baseball throw motion you would for your serve. Launch your body upward energetically and hit the ball when your arm is fully extended. Unlike the serve, your swing does not have to be continuous, though the more rhythmical your motion, the better. Follow through almost as fully as you would on the serve.

To achieve maximum power, generate as much racket head speed as you can control. What is commonly referred to as the “wrist snap” is actually a pronation involving your shoulder, forearm, and wrist. Your shoulder and forearm rotate down, while your wrist flexes (bends) forward. At the contact point, your racket face will be flat. Pointing toward the oncoming lob with your left arm will help you in three important ways. First, it will help you turn sideways and thus set up the hip and shoulder rotation. Second, you can line up the flight of the ball by pointing at it. Third, extending your left arm will improve your balance. After you smack the overhead, don’t assume it’s a winner, unless you definitely bounce it over the fence or into the stands. If you’ve hit a powerful overhead that forces your opponent to scramble, sprint forward to regain your position at net and be ready either for a volley or another overhead. However, if your overhead is not that strong and you find yourself in no-man’s land, it may be prudent to retreat to the baseline. There you can try to regain the offensive. Vary the Contact Point Every shot has an ideal contact point. Unlike the flat serve, the contact point for the overhead changes because your position on the court varies dramatically. Your goal is to avoid hitting the ball too short (in the forecourt) or too deep (beyond the baseline). If you strike the ball from near the service line, your contact point will be above your right shoulder to about 6 inches in front of your body, depending on your height and reach, with your arm fully extended. If you strike the ball five feet from the net, your contact point will be slightly more in front. That’s because you have less distance to hit the ball safely into the court. Conversely, overheads hit from 10 feet inside the baseline should be contacted slightly less in front. Another variable is where you aim your overhead. If you smash straight ahead, your contact point will be slightly more in front than if you smash crosscourt, because the distance is shorter straight ahead. Like the flat serve, you should contact the ball on the overhead slightly to the right of your body, at 1 o’clock for right-handed players, if you think of your head as the center of a clock face. Slice overheads should be hit at 1:15 to 1:30 o’clock. The farther to the right the contact point is, the more slice and less power you’ll produce. If you can’t put the ball away—because you can’t get enough weight transfer or racket head speed—you may decide to use a small amount of slice to create a well-placed, crosscourt overhead. Slice overheads can be hit safely from the center or the right side of the court, but are low-percentage shots from the left side of the court because they can swerve into the alley. In singles, it is vital to smash decisively to both sides of the court to keep your opponent honest. In doubles, smashes up the middle will win many points. So target all three areas when practicing smashes from various parts of the court.

Dealing with the Elements Sun, wind, and rain pose the biggest problems. A bright sun can almost blind you, so expect lobs from savvy opponents when you’re facing the sun or during midday. If you let a lob bounce, you can often see the ball better from a different angle. That will lower the odds you’ll mishit it or err. Remember: you can still put away many bounce overheads. Some players don sunglasses on sunny days, or only when they play on the sunny side of the court. Windy conditions, especially swirling or gusting currents, can befuddle even the most proficient and confident smashers. Watch the ball intently with your head tilted up. Taking small adjustment or corrective steps will help you move wherever the wind takes the ball. When you’re in doubt, it is always better to position yourself a couple extra feet behind the ball and an extra foot to the left of the ball. To align your body properly for the lob, it’s always easier to move forward than backward and also easier to move to the right than to the left at the last split-second.

If the ball is sailing erratically and unpredictably in the wind, you may have to settle for less power and more control, or even let the ball bounce, to avoid an error. The same advice applies in the rain, along with exercising patience. On clay courts and with balls made slower by rain, you may need two or three overheads to win the point. The other occasions to let the ball bounce are when you don’t arrive in time to smash it in the air, when the lob is extremely high, when there is a reasonable chance the ball may land in the alley or beyond the baseline, and when the lob may not clear the net or will land very close to it. In the latter two cases, be careful not to touch the net with your racket or body. Those infractions will cost you the point. Who can forget Novak Djokovic lunging into the net for a tricky angle tap overhead and losing what would be the turning point of the 2013 French Open final against Rafael Nadal? Power vs. Placement “You have to put that overhead away. That’s the difference between the good and the great,” rightly averred Tennis Channel analyst Paul Annacone, the former coach of Sampras and Federer, at the 2015 Mutua Madrid Open. Thanasi Kokkinakis, a fast-rising Australian teenager, had just failed to put away an overhead in the hard-fought, fluctuating eighth game of the deciding set in which American veteran Sam Querrey broke serve. It proved costly for Kokkinakis, as Querrey prevailed 6-4, 6-7, 6-3. For decades, leading players, coaches, and teaching pros have debated the merits of power versus placement on the overhead. Both Bobby Riggs, who captured all three events at the 1939 Wimbledon, and 1950s−60s champion Ken Rosewall had highly effective overheads because of accuracy rather than power. However, they were 5’7” precision players, exceptions from the wood racket era, who tested—rather than disproved—the rule that the smash is the ultimate power shot. Those who contend that power must be moderated and placement emphasized to achieve consistency ignore two points. First, you don’t need pinpoint accuracy on the overhead. If you aim for a target about five feet from the sideline and five to 10 feet from the baseline, you will have plenty of margin of error. Put differently, with considerable power and sufficient placement, you’ll have the best of both worlds to put the ball away consistently. Second, even with the best placement, today’s taller and faster players will often run down and return well-placed overheads that aren’t hit hard enough, particularly those struck from behind the service line. Surprisingly, world No. 1 Djokovic is guilty of not putting away some routine overheads he strikes just behind the service line. Actually, a lack of depth is a greater shortcoming than inaccuracy—except for smashes intentionally hit sharply crosscourt from inside the service line. That’s because the speed of the ball decreases sharply after it hits the court, especially if it bounces high. That extra time allows your opponent to track the ball down.

Avoid the Backhand Smash In Game, Set and Match: Secret Weapons of the World’s Top Tennis Players, two-time US Open titlist Patrick Rafter rightly recommends practicing the backhand smash. It’s probably the most under-practiced supplementary shot in tennis along with the lob. But he wrongly asserts, “Most people are a bit lazy, and run around and play a normal smash on the other side.” In truth, players should avoid the backhand smash and play a normal smash as much as possible. That’s because a standard forehand smash is far more powerful than a backhand smash, even for the strongest backhand smashers, such as 6’4” Stan Smith. In women’s tennis today, the high backhand swinging volley has become the weapon of choice when they can’t position themselves to hit a regular overhead. It’s also more powerful than their backhand overhead. However, this shot selection can be overdone. Maria Sharapova almost always opts for high backhand swinging volleys and thus often fails to hit winners off lobs. Since some opponents will hit the vast majority of their lobs to your backhand side, you can counteract that with early anticipation and quick reactions. The other keys are to split step and then step back with your right foot and turn your hips and shoulders to the right. Then you should side-pedal backward diagonally with quick crossover steps. “For a deep lob, longer distances must be covered quickly, so a crossover, scissor step is preferred,” says Pat Cash, the 1987 Wimbledon champion and a master smasher. “This is the quickest and most powerful way to sprint backward, and it’s also beneficial when you leap in the air. This movement is recommended for all but simple put-aways close to the net when shuffle steps are acceptable. Crisscross, backwards movements allow you to get well behind the ball quickly followed by any shuffle steps and adjustments until the ball is positioned in the right place for contact.

“Ideally, you should contact the ball with your body almost face on to the net, much like the best servers in the world do on their serve,” says Cash, who coached Mark Philippoussis and Greg Rusedski. “For most club players, the body position at contact tends to mirror that for the serve.” That similarity can cause them problems because “your technique weakness in your serve will be the same issue with your smash,” notes Cash. “If you’re too ‘side on,’ you could have a poor contact position in relation to the ball, have bad elbow movement, duck your head down, or not follow through properly.” Watch videos to study how former stars Martina Navratilova, Justine Henin, Sampras, and Cash (his coaching App is called Pat Cash Tennis Academy) quickly maneuver into position, particularly for lobs to their backhand side. Among active players, Federer and Nadal are superb at avoiding backhand smashes and putting away lobs targeted at their backhand. Study Your Opponent's Lob When you scout your opponent, don’t forget his lob. Ask yourself these pertinent questions. Does he typically lob more often on his forehand or backhand? Do his lobs have underspin, topspin, or virtually no spin? Does he usually lob crosscourt, down the line, or to your backhand side? Does he lob more often or less often on big points? Do his lobs have a high, low, or medium trajectory? Does he lob mainly when you position yourself very close to the net? Does he give away his intentions to lob by lowering and slowing down his backswing, or does he disguise it masterfully like former world No. 1s Lleyton Hewitt and Arantxa Sanchez Vicario? Armed with this information about your opponent’s lobbing tendencies, you can smash more effectively and consistently. For example, since topspin lobs drop fast, you’ll have to react more quickly to reach them, and you’ll also need impeccable timing to avoid swinging late and mishitting them. If your opponent rarely lobs or does so poorly, you can position yourself closer to the net than you normally would, a tactic that will make your volleys more effective. And, if both his passing shots and lobs are weaknesses in his game, go to the net more than usual, especially if your volleys and smashes are your strengths. Drills For Skills If you’re a beginner or intermediate player, have a friend or coach loft shallow and low lobs right to you to build your skill, timing, and confidence. Stand halfway between the net and service line and take a step or two at the most. As you become more adept, the lobs can gradually go somewhat higher and deeper. If you’re an advanced or tournament player, your partner should vary the lobs in every respect after a few easy warm-up lobs to your forecourt. The lobs should come from different spots, ranging from behind the alleys to behind the center strip and from one to 10 feet behind the baseline. An unpredictable mixture of high, medium, and low lobs, as well as underspin, flat, and topspin lobs should target every part of the court. Change sides of the court so you will face the sun and hit with and against the wind. After side-pedaling back for each lob, you must sprint forward and tap the middle of the net.

Have your partner or an observer keep a mental or written record of the lobs that give you the most trouble as well as why and how you mishit them. In subsequent practices, concentrate on these weak areas until you master them. This drill will improve your technique, speed, agility, and stamina. Conclude every overhead session by playing the Overhead Game. The lobber starts every point behind the center of the baseline with the lob of his choice. The smasher starts every point eight feet from the center of the net and returns there after every smash. The smasher is allowed to hit bounce overheads only when absolutely necessary. The lobber must return every overhead with another lob. The first player to reach five points (no tiebreaker) wins the game. While the smasher is the favorite to prevail, he should always strive for a 5-0 shutout. This exhilarating game, with each player being a smasher and lobber, is also a fun, competitive way to end entire practice sessions. The smash is the potential home run of tennis. “Without being reckless, you should ‘deck’ the ball hard and deep as often as possible,” distinguished coach Vic Braden advised in Vic Braden’s Quick Fixes. “You’ll miss an occasional overhead hitting like this, but it’s a far better way of playing than merely punching the ball like Mickey Mouse the entire match.” When it comes to smashes, don’t be Mickey Mouse. Be King Kong. * * * * * Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Paul Fein's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Paul Fein Paul Fein has received more than 30 writing awards and authored three books, Tennis Confidential: Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies, You Can Quote Me on That: Greatest Tennis Quips, Insights, and Zingers, and Tennis Confidential II: More of Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies. Fein is also a USPTA-certified teaching pro and coach with a Pro-1 rating, former director of the Springfield (Mass.) Satellite Tournament, a former top 10-ranked men’s open New England tournament player, and currently a No. 1-ranked Super Senior player in New England. |