|

TennisOne Lessons Why the Strike Zone Is So Important in Tennis Paul Fein After wily veteran Andy Murray defused the power game of rising star Nick Kyrgios in the Australian Open quarterfinals, Murray revealed a key tactic: “Nick is a huge hitter of the ball, so I tried to keep it out of his strike zone. It was quite windy, so if you can use the slice and keep the ball low, it is difficult [for your opponent] to control it. I played a slightly different style tonight, and it worked.” Tennis players, coaches, and TV analysts borrow the analogous term “strike zone” from baseball.* In the intriguing battle of wits between pitcher and batter, the pitcher targets the outer edges of the strike zone with a diverse array of pitches to try to confound the batter. At their deceptive best, pitchers throw balls that look like strikes but end up outside the strike zone, and vice versa. Batters, unlike tennis players, don’t have to swing at difficult pitches outside the strike zone called “balls”, but often they are enticed to.

Tennis also has a strike zone, though its dimensions are not defined in the rules, as in baseball. (See the sidebar.) The smaller tennis strike zone—from the upper thigh to the upper abdomen—particularly its center, is similarly the best place to contact the ball. The crucial difference, however, is that while baseball pitchers must throw to a stationary batter into a stationary strike zone to have the pitch called a strike by the home plate umpire, tennis players must move constantly to create strike zones of their own. Clever, versatile players like Murray, Roger Federer, Rafael Nadal, and Agnieszka Radwanska test their opponents’ improvisational and technical skills by probing and attacking with shots outside their foes’ strike zones. Who wins these subtle games can often determine the winner of the match. Let’s look at four ways you can take your opponent out of his strike zone and how you can counteract those tactics yourself. The Body Serve Rightly called the most under-used and under-rated serve in tennis, the body serve is analogous to the inside pitch in baseball. Both deliveries cramp the hitter and prevent him from leveraging his power. The tennis server tries to “handcuff” the receiver with a viciously swerving slice serve into the receiver’s right hip. This tactic works best against a player who is tall, slow, or un-athletic and one with poor footwork or strokes. If you have terrific power, it can also intimidate him, much like a brush-back pitch in baseball. The cerebral Murray used the body serve to surprise the inexperienced Kyrgios in the tiebreaker of Murray’s 6-3, 7-6, 6-3 victory. On the pivotal 4-all point, Kyrgios reacted late. Off-balance, he over-hit a forehand beyond the baseline. Conversely, predictable Tomas Berdych rarely hit body serves, especially in the deuce court, against Murray, a superb returner. As a result, Murray easily “read” Berdych’s serve and usually returned it strongly. The body serve is used increasingly by women who are serving faster than ever. Nineteen women hit serves 115 mph or more at the 2015 Aussie Open, compared to 10 a year ago. “I don’t think I’ve ever seen anyone use the body serve as much as Venus [Williams] in this tournament,” noted Tennis Channel analyst and all-time great Martina Navratilova. “And it worked especially well against Radwanska.” Fearless comers Garbine Muguruza, Camila Giorgi, and Madison Keys also deployed body serves successfully and fairly often. (Two parallels of the body serve are passing shots and volleys belted at the netman’s right hip and serve returns pounded hard, deep, and up the middle at the server before he can regain his ready position.)

How to handle the body serve — Move your feet quickly away from the oncoming ball, or if you're out of time, simply lean away so you can extend your arms as much as possible. Shorten your backswing, or even just block the ball back. You can also change your receiving position from time to time to keep the server guessing where you're actually positioned. Above all, watch the ball toss, wrist pronation, and ball contact of the server to anticipate the placement, power, and spin of the serve. That will help you react quickly and correctly to body serves.

The Low Ball Murray sliced low backhands artfully against the 6’4” Kyrgios and the 6’5” Berdych, who both lack the athleticism of Federer and flexibility of Novak Djokovic. The low-bouncing shots achieved three goals. First, they induced opponents to make groundstroke errors, usually in the net, because it’s difficult, particularly for Western forehand players like Kyrgios, to get the correct, upward trajectory. Second, they prevent, or at least discourage, opponents from attacking. Third, they throw off the rhythm and timing of opponents. As Murray pointed out, when used with the wind at your back, sliced balls are highly effective because they accelerate and bounce even lower. Court surface also determines how often you should slice. Fast and slippery grass made the nasty backhand slices of Federer and 22-time Grand Slam champion Steffi Graf downright vicious. Slices also work well against tall players like Maria Sharapova and two-handed backhand players, such as Simona Halep, who are not comfortable with one hand off the racket when they are forced to hit slice returns. How to handle the low ball — You must move as speedily as possible to get to low balls at their highest bounce point; and when you arrive, bend your knees as much as necessary. As you run, determine the return that has the best reward-risk ratio: be as aggressive as you can be without risking an error. That decision also entails leaving yourself with enough time and in a tenable enough position to return your opponent’s next shot. If he, like Murray, likes to follow a slice with a powerful shot, you have to be ready to defend extremely quickly. The Wide Serve The slice serve is akin to the baseball slider that curves down and away from the batter. With pinpoint placement and plenty of slice, the first serve in the deuce court can be devastating because the returner is yanked way off the court. Even if he returns the serve, nearly the entire court opens up for your next shot. You don’t have to possess the strength of Hercules for this essential serve. You need the Continental grip and a toss to the right of the 1 o’clock placement of your flat serve. Experiment with different toss placements to produce different amounts of power and spin. Berdych, who previously lost 17 straight times to Nadal, won points repeatedly with wide serves to stun the 14-time Grand Slam titlist 6-2, 6-0, 7-6. Exploiting Nadal’s questionable return position about ten feet behind the baseline, Berdych dominated the deuce court points as the scrambling, out-stretched Nadal was aced, erred, or hit weak returns that Berdych put away. Conversely, Berdych did something Federer and other players rarely do: he moved forward and attacked Nadal’s swerving lefty slice serve, so Nadal seldom started the point with an aggressive forehand, his breadwinner. Murray, playing his most efficient and inspired tennis since controversially hiring Amélie Mauresmo as coach, also used the slice serve to great advantage in both the deuce and ad courts. As 1987 Wimbledon champion Pat Cash wrote in The Times (UK): “ The way Murray has found the ability to curve the ball low [and] away from the deuce court is spectacular. He puts a huge amount of bend on the ball so it flies away across the tramlines and makes it virtually impossible for the player at the other end. He can also employ slice going into the advantage court as well. Standing very tight to the centre of the court, he will get the ball to bounce as near the T of centre line and service line as possible. But then the ball will veer away to the left, again forcing the returner to stretch into the shot.”

The effective wide serve has another benefit. When returners position themselves closer to the singles sideline to defend against it, smart servers capitalize by serving up the less-protected middle. Super-server Serena blasted 18 aces (15 in the second set!) and three service winners to all four corners of the two service boxes in her riveting 6-3, 7-6 final victory over Sharapova. That variety, which included plenty of wide serves, kept Sharapova guessing and prevented her from even re-positioning herself nearer to the sideline. “It’s a fascinating matchup—like the pitcher against the batter,” noted Navratilova, about Serena’s shrewd serve selection. How to handle the wide serve — Evaluate how often and effectively your opponent is hitting it, and base your return position on that. If his first serve isn’t that fast, hold your ground near the baseline. And if his slice isn’t that severe, don’t shift much to the right in the deuce court. Try to determine from his service toss if he’s slicing. Watch the ball intently because it’s curving sharply and a mishit will prove costly. The High Ball Whether it’s generated by a kick serve or a topspin groundstroke, the high-bouncing ball can bedevil even the pros. If you have a one-handed backhand or an Eastern forehand, are short, or lack first-rate hand-eye coordination, you may be bewildered by balls that bounce above your shoulder, or even your head. Federer hasn’t beaten Nadal at a Grand Slam event since the 2007 Wimbledon, and Nadal’s 23-10 career domination is largely due to his punishing the Federer backhand with viciously spinning, high-bouncing forehands. The determined but vertically challenged 5’3” Dominika Cibulkova, runner-up at the 2014 Aussie Open, was thwarted by the high-kicking second serve of Serena Williams during Serena’s 6-2, 6-2 rout this year. On the other hand, the 6’ Muguruza found Serena’s kick serves right in her much-bigger strike zone and she attacked them relentlessly. Although Serena avenged a 6-2, 6-2 whipping from the 21-year-old Spaniard at the last year’s French Open, she won only 42% (15 of 36) of her second-serve points during her 2-6, 6-3, 6-2 victory in Melbourne. How to Handle the High Ball Try to intercept it before it bounces high. For a topspin groundstroke, it’s crucial to judge accurately the flight of the ball—its trajectory, spin, speed, and likely bounce point. Then arrive there in time and balanced so you can set up for a solid shot with your weight moving forward. You don’t have to run far for a kick serve, but it can come faster and bounce higher than groundstrokes. So you have to be quicker, stronger, and even sounder with your technique, particularly in doubles where a weak return will be put away by the netman. Study videos of how Djokovic handles Nadal’s ferocious forehand and how Djokovic controlled the high-bounding serves of Milos Raonic in his 7-6, 6-4, 6-2 quarterfinal drubbing of the 6’5” Canadian at the Oz Open. Quick Quiz What do all these tactics have in common? If you answered “spin,” you’re either a smart student of the game or a player who already uses the strike zone to your advantage. Whether you’re a keen analyzer and or an aspiring player, make the strike zone a pleasure zone in your tennis experience.

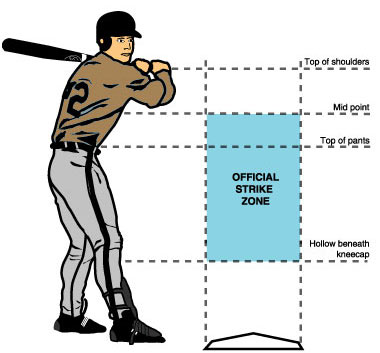

Major League Baseball defines, in the most recent issue of its official rule book (Definition of Terms — 2.00), a baseball strike zone with the following description: The STRIKE ZONE is that area over home plate the upper limit of which is a horizontal line at the midpoint between the top of the shoulders and the top of the uniform pants, and the lower level is a line at the hollow beneath the knee cap. The Strike Zone shall be determined from the batter's stance as the batter is prepared to swing at a pitched ball. “The game is all about control of the seventeen-inch triangle. Hitters who force pitchers to stay in the strike zone are productive, and pitchers who take hitters out of the strike zone are dominant.”— Oakland Athletics General Manager Billy Beane on ESPN.com (Peter Gammons, 09/08, ‘Contenders’ flaws add intriguing plot twists, like any great drama’ Source)

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Paul Fein's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Paul Fein Paul Fein has received more than 30 writing awards and authored three books, Tennis Confidential: Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies, You Can Quote Me on That: Greatest Tennis Quips, Insights, and Zingers, and Tennis Confidential II: More of Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies. Fein is also a USPTA-certified teaching pro and coach with a Pro-1 rating, former director of the Springfield (Mass.) Satellite Tournament, a former top 10-ranked men’s open New England tournament player, and formerly a No. 1-ranked Super Senior player in New England. |

||||||||

* Sidebar

* Sidebar