|

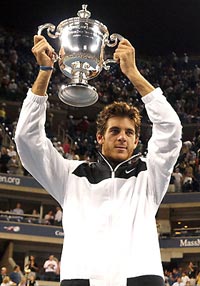

TennisOne Lessons Techniques, Tactics and Controversies at the Surprising U.S. Open Paul Fein “Sports is the only entertainment where no matter how many times you go back, you never know the ending.” Who would have predicted Juan Martin del Potro and Kim Clijsters would win the U.S. Open? Nobody would have predicted both surprise champions, but the 20-year-old del Potro was hardly “an underdog of almost unimaginable proportion” in the final, as an ESPN.com columnist asserted. And former world No. 1 Clijsters, who captured the 2005 Open and gained the 2003 final, possessed the game and experience to knock off high-ranking opponents.

How did del Potro and Clijsters surmount tough draws to prevail? What about the upsets, meltdowns, comebacks, and rising stars? Let’s analyze these and other highlights of the most colorful and controversial Grand Slam tournament of 2009. Juan Martin del Potro Technique – Like Marat Safin, who also stunned a legend, Pete Sampras, at age 20 in his first major final, the 2000 U.S. Open, the 6’6” Argentine boasts terrific strokes and first-rate footwork. This year he added much more power to his serve with three vital changes: more wrist snap, greater use of his legs, and a ball toss more in front of him. In the final his fastest serve rocketed at 138 mph. No. 6-ranked Delpo, as his friends call him, also blasted 37 forehand winners, including two measured at an astounding 110 and 108 mph. Besides those two huge weapons, his super-solid two-handed backhand packed more power and control than Federer’s vulnerable one-hander. “Maybe the backhand was the key to the match because Roger serves so well,” said del Potro. While his volley technique looks sound, his net game will improve when his agility, reflexes, and anticipation improve. Still, he impressively won 68% (23 of 34) of his net approaches against Federer, 71% (17 of 24) against Rafael Nadal, 71% (12 of 17) against Marin Cilic, and 85% (11 of 13) against Juan Carlos Ferrero. Technically, his game is already complete. Tactics – Pure power players, such as del Potro, generally need and use less strategy than other stylists. Like towering Lindsay Davenport, he clearly understands the importance of getting on the offensive immediately behind big serves and service returns to minimize his relative weaknesses, movement and stamina. Del Potro confided that his legs cramped at the end of the fourth set against Federer.

He rightly concentrated his attack chiefly on Fed’s backhand, but directed enough serves and groundstrokes to his forehand to keep Fed honest. Midway through the final, del Potro decided to take power off his booming first serve – which he effectively sliced away from Federer or into his body – and to increase his groundstroke firepower. That tactic worked. Del Potro can be faulted for hitting too many approach shots crosscourt and for receiving Fed’s first serve from too far (about 10 feet) behind the baseline. But as his confidence grew, he gradually moved closer to the baseline and dictated most rallies. Five-time Open champion Federer, despite his matchless defensive skills and dazzling shotmaking, was simply overpowered in the final set of the 3-6, 7-6, 4-6, 7-6, 6-2 dethronement. Prognosis – After the final, Federer graciously noted: "It's always an amazing effort coming through and winning your first [major title] in your first final. You have to give him all the credit, because it's not an easy thing to do, especially coming out against someone like me who has so much experience." Indeed, the soft-spoken del Potro admitted the occasion "weighed heavily on me" and "I couldn't sleep" the night before. Make no mistake: del Potro’s tour de force at the Open was no fluke. During the past 15 months, del Potro dramatically improved. At the Australian Open in January, he won a mere three games against The Mighty Fed, while at the French Open he bowed 6-4 in the fifth set to the 28-year-old Swiss. Del Potro is the only player to beat Nadal thrice in one year (including a 6-2, 6-2, 6-2 thrashing at the Open) and to conquer both Nadal and Federer in the same Slam tournament. Despite a jittery start that cost him the first set, and two straight double faults that gave away the third set, del Potro displayed unflappable poise to win both tiebreakers (Federer was 18-3 in tiebreakers in Slam finals before that!) and true grit to rebound after trailing two sets to one. His Achilles heel may be stamina, particularly in hot weather. If he improves his conditioning, don’t be surprised if he captures the 2010 Australian Open on hard courts, his favorite and best surface. Andy Murray Technique – As astute ESPN analyst Patrick McEnroe maintained, “In the men’s game now, you need to play great defense and great offense. And I don’t believe Murray has great offense yet, consistently.” In fact, 2nd-seeded Murray showed very little offense in his embarrassing 7-5, 6-2, 6-2 debacle against 16th-seeded Marin Cilic, a competent but hardly overwhelming opponent. The 22-year-old Scot can’t blame defective technique, though he must substantially increase the speed and spin on a second serve that averaged a wimpy 83 mph in his four matches. Although Murray’s return of serve is touted as among the tour’s best, it let him down against Andy Roddick at Wimbledon and was downright poor against Cilic.

In his post-match press conference, Murray often used the word “disappointing” but missed the point when he said, “There were very few long rallies after the first set, and normally, you know, I’m able to get myself into rallies.” Why? Let’s talk tactics. Tactics – The International Tennis Federation classifies the U.S. Open's DecoTurf hard courts at the second-fastest of five levels of speed: medium-fast. Therefore, on a surface that heavily rewards aggression, Murray's tactic should not be to "get into long rallies." With his strongly built 6’3” physique, near-perfect strokes, athleticism and shot-making versatility, he should attack at every opportunity, as Federer and del Potro do. Second, he should use early round matches to work on creating and consummating aggressive two- and three-shot combinations, so in the later rounds he will have the skill and confidence to execute that against elite foes. Third, Murray hits almost every passing shot crosscourt, and that won’t work against topnotch volleyers. Fourth, on fast, high-bouncing hard courts, he should hit far fewer drop shots but more sharply angled groundstrokes, like Federer and Serena Williams. Fifth, he must come to net much more often to pressure

opponents and finish off points. In his loss to Cilic, he approached only eight times. Prognosis – "There is nothing harder in tennis than living with expectations," 1980s doubles superstar Pam Shriver perceptively pointed out. She was referring to underachieving world No. 1 Dinara Safina, but great expectations have seemingly weighed down Murray, too. The rising star came into the U.S. Open after taking five titles this season, including four on hard courts, his favorite surface. He had also beaten Federer four of the last five times, Nadal two of the last four times, Novak Djokovic the last three times, and del Potro two of the last three times. As Murray noted, “I’m the defending finalist. People are expecting me to step up.” Instead, he fell down dismally against Cilic. Since Murray relishes analyzing various aspects of the sport, he and his brain trust should conclude that cagey but soft shots won’t fool high-ranked opponents much longer and certainly not at the majors. He should stamp “Power” on his sneakers and rackets and adopt that style. But will he? Novak Djokovic Technique – Nicknamed "The Djoker" for his hilarious impersonations of other players, the 22-year-old Serb looked like the heir apparent to Federer after he whipped him in straight sets en route to capturing the 2008 Australian Open, his sole major title. It didn't happen. This year he made only one semifinal at a major and an easy draw at Flushing Meadows helped. Djokovic’s only technical shortcomings are a forehand that sometimes generates too much spin (and too little power) and a volley that needs more pace. He won only 45% (9 of 20) of net approaches against Federer in his 7-6, 7-5, 7-5 semifinal loss.

Tactics – Coaches Marian Vajda and Todd Martin have their work cut out for them because Djokovic's tactical sense can range from mediocre to non-existent. He committed the cardinal sin of hitting too many shots to the devastating Federer forehand – and often on crucial points. For example, on set point of the pivotal second set, Djokovic directed every ball to the Fed forehand, and not surprisingly, Fed eventually belted a forehand winner from the middle of the court. Second, Djokovic regularly misses chances to move forward and pounce on weak shots. Third, Djokovic aimlessly slices his backhand, which allows Federer

(and others) to attack; instead he should be attacking, or at least keeping the pressure on, with his strong two-handed backhand. Fourth, since he boasts one of the tour’s best service returns, especially on the backhand, he should attack second serves more. Fifth, he drop-shots too much, especially on hard courts and on important points; and he frequently loses them. Sixth, like Murray, he enjoys toying with opponents rather than putting the ball away. On the brink of defeat at love-30, 5-6 in the third set, Djokovic foolishly lob-volleyed and Federer ran it down to zap a spectacular back-to-the-net, between-the-legs passing shot winner. Prognosis – Djokovic is blessed with an ideal tennis physique and considerable athleticism. His sound strokes, albeit without a huge weapon, are other assets. That said, I’ve rarely seen a top player look and sound so happy after tough losses in majors than The Djoker – “If you ask me if I had fun today and enjoy it, yes, I did, absolutely,” he said after Federer beat him – or one who withdraws so often during matches. Unless he competes harder and smarter, he’ll never capture another major title. After losing 6-1, 7-5 to Federer in the Cincinnati final in August, Djokovic may have signaled his resignation when he said, “Unfortunately, I was born in the wrong era.” The Women Kim Clijsters Technique – Before her 2007 retirement, Clijsters's career coincided with an extraordinary era, the primes of Serena and Venus Williams, Justine Henin, Lindsay Davenport, Jennifer Capriati, and Maria Sharapova, all champions with more power. Yet at the majors, she won once and reached four other finals and seven semifinals. She also grabbed 34 singles titles, including two season-ending WTA Championships.

The popular Belgian did it with a high-percentage game that boasted an excellent return of serve, strong groundstrokes, and a solid serve. Her superior speed and anticipation made her a terrific defensive player. True, Clijsters lacked a devastating weapon and her forehand occasionally betrayed her, but she suffered few bad losses and usually only the best players at their best beat her. On Clijsters’ remarkable comeback – the Open was only her third tournament after a 27-month retirement – Serena remarked, “It looks like she has only been gone a week.” Four factors made her quick comeback much less surprising than some pundits predicted: her uncomplicated and smart game, high fitness level, unquenchable competitiveness, and the mental and physical fragility and inconsistency of almost all the elite players. (Only one of the top eight seeds made the quarterfinals.) Tactics – Clijsters doesn't vary her tactics much from opponent to opponent, although she certainly is savvy enough to zero in on weaknesses such as Venus's erratic forehand and Caroline Wozniacki's slow second serve, which averaged only 74 mph. Her high-percentage, deep topspin groundstrokes elicited 31 "unforced" (actually, mostly semi-forced) errors from an impatient and frustrated Serena. Against the counter-punching Wozniacki in the final, Clijsters judiciously attacked to produce 36 winners, while her defensive prowess limited her opponent to just 10.

Prognosis – Since Clijsters will undoubtedly continue to compete at a top 5 level, her fate lies mostly in the hands and rackets of the other contenders. Some of Serena's great success in the past 16 months resulted from the retirement of the great Henin, who whipped her in three Grand Slam quarterfinals in 2007. Declining speed and mediocre footwork may hasten Serena's decline, while explosive but error-prone Venus, now 29, hasn't reached a major final (and only one semifinal) since 2003, other than at Wimbledon. Will Sharapova and Ivanovic rebound completely from injuries? Can world No. 1 Safina and highly talented Kuznetsova conquer their nerves? Will Jelena Jankovic, who finished 2008 ranked No. 1, recover from her 2009 slump? How much will rising stars Wozniacki and Victoria Azarenka improve? Will another teen phenom suddenly emerge? And most interesting of all, how quickly will Henin, who announced her comeback on Sept. 22, regain the form that produced seven major titles and an Olympic gold medal? Questions abound. Caroline Wozniacki Technique – A younger version of Clijsters, Wozniacki is also blessed with athletic genes (her father played pro soccer and her mother played volleyball for the Polish national team), competes relentlessly, and is a cheerful, down-to-earth blonde. Her service return and backhand, though not big weapons yet, are strengths, along with a high-percentage topspin style. Both her first and second serves need more power, her volley technique can be shaky, and she sometimes plays too far behind the baseline. Tactics – "I tried to play the same style as Hingis when I was coming up, not so much power but thinking," says Wozniacki, little Denmark's first woman to make the top 10 and first Slam finalist since Kurt Nielsen in 1955. However, like Hingis, she will run into trouble trying to defuse the power of today's sluggers. That said, she was exceedingly impressive, especially on the big points, in overcoming the explosive sixth-seeded Svetlana Kuznetsova 2-6, 7-6, 7-6 in the fourth round.

Prognosis – Her boundless love of the game, willingness to learn, sound groundstrokes, and strong work ethic – she has worked with Gil Reyes, Andre Agassi's renowned trainer – should keep her in the top 10 during the next decade. But to win major titles, she clearly must develop point-winning shots. Melanie Oudin Technique – Melanie Oudin, a 17-year-old blonde from Marietta, Georgia, burst on the world tennis scene by knocking out No. 6 Jelena Jankovic to reach the fourth round at Wimbledon. When No. 70-ranked Oudin upset No. 4 Elena Dementieva 5-7, 6-4, 6-3 at Flushing Meadows, Pam Shriver, a 1980s doubles superstar and now an ESPN analyst, called it "the biggest win for a teenager on the women's side in the United States since Serena Williams won this title ten years ago." The Cinderella story continued with two more come-from-behind shockers, over three-time Slam champion Maria Sharapova 3-6, 6-4, 7-5 and No. 13 Nadia Petrova 1-6, 7-6, 6-3, before Wozniacki stopped her 6-2, 6-2 in the quarters. Amazingly, Oudin’s overall technique appeared rather ordinary. Her flat forehand produced a few timely winners, but her flat two-handed backhand lacked the power to threaten opponents, although her one-handed slice kept her in points when she was scrambling defensively. In Oudin’s three big wins and quarterfinal loss, her first serve averaged only 93 mph, and she averaged winning only 57% of her first serve points. Her second serve averaged just 78 mph and generated little spin. The 5’6” Oudin was fortunate her three highly regarded Russian victims hit flat, relatively low balls she could handle. Wozniacki exposed her weaknesses, though, with deep, accurate and high-bouncing topspin shots. Oudin would do well to take the advice renowned Australian coach Charlie Hollis gave future great Rod Laver as a youngster: "Short blokes can't hit flat balls. Big men don't need spin, but the little runts like you do." Tactics – Oudin idolizes Henin and said, "She proved you don't have to be 6-foot-something to be No. 1. She figures out a way to take down these players that overpower her with her variety and her movement." While Henin's assets did include versatility and movement, the 5' 5¾" Belgian also won with power (her serves often hit 110 mph) and Federer-like athleticism. Oudin actually resembles patient, clever counter-puncher Martina Hingis, without her topspin, sharp angles and deceptiveness. Aside from her lack of topspin, Oudin plays the percentages exceedingly well with her shot selection. Her exceptional footwork and court coverage allow her to escape from seemingly untenable positions by stroking very deep groundies. That scrappy steadiness and just enough offense worked against the sometimes erratic Russians on a hard court before wildly partisan fans. How well Oudin will fare on clay, grass, and hard courts when the rest of the tour learn more about her game remains the intriguing question. Prognosis – After upsetting Petrova, Oudin maintained, "It's not all about power, it's about how tough you are mentally and how smart you are on the court." By displaying her best tennis on the biggest stages, fearless Oudin has already proved she possesses the intangibles of a champion. But unless she adds power and spin, she won't have a top 10 game. The Foot Fault That Freaked Out Serena Richard Williams used to say that his youngest daughter Serena had a mean streak. Slogans on shirts she wore at U.S. Open post-match press conferences hinted at a dark side: “Can’t spell dynasty without nasty” and "Vicious, ambitious and delicious.” It was easy to shrug off the messages as extroverted Serena being Serena and just seeking attention and perhaps a few laughs. But we all saw a vicious, nasty Serena curse and threaten a lineswoman who was doing her job when she called a foot fault at a critical stage of Serena's 6-4, 7-5 semifinal loss against Clijsters. Brandishing her racket and striding menacingly toward the line judge, Serena yelled, "If I could, I would take this f---ing ball and shove it down your f---ing throat and kill you." ESPN analyst Mary Carillo put the ugly incident in perspective when she told ESPN.com: "Serena can be disingenuous off the court, make excuses and not give her opponents credit, but I will always remember her and Venus for being incredibly fair and honest on the court. Serena doesn't argue line calls. She doesn't even [use the Hawkeye] challenge. She usually just gets on with it. I've always really admired her for that. This was an aberration. I've never seen her like that."

Why did Serena erupt like that? A self-described “intense and prideful” competitor, she was frustrated at missing shots she normally makes and was on the verge of defeat against a player she was favored to beat. But a second important reason is that Serena apparently didn’t understand and respect the duty of the linesperson. Serena’s attitude was: “But you can’t call a foot fault now!” It’s instructive to revisit the 2001 U.S. Open, where a similar controversy occurred. When Lleyton Hewitt, another fiery competitor, angrily protested two foot faults, he charged that the fault was with the linesman, not him. Frustrated because he was losing to heavy underdog James Blake, Hewitt implied the foot faults were racially motivated because the linesman, like Blake, was an African-American. That a linesman could and would call two foot faults on him seemed implausible, if not outrageous, to Hewitt. Television commentators rightly criticized Hewitt for his offensive racial innuendo, but not for his failure to abide by the time-honored foot fault rule. However, I have often heard TV analysts take the player's side and complain: "No way can you call a foot fault on Joe Blow at 4-all in the third set, especially when it's the first foot fault of the match." Why not? A linesperson should call a foot fault any and every time it occurs. In fact, that is one of his main responsibilities. Yet these TV commentators sound earnest and dogmatic enough to hoodwink viewers not conversant with the foot fault rule. (Cliff Drysdale rightly defended the lineswoman in the Serena incident.) Touching the baseline or inside the court with either foot before striking the ball is one of the four ways a server can foot fault, and by far the most common. As a former linesman who occasionally worked the baseline, I can attest that calling foot faults is a demanding assignment. For example, a player’s sneaker may step or slide within a hair’s breadth of the baseline before his racket makes contact with the ball. His sneaker may also clearly touch the baseline, but whether that happened a split second before or after the serve was struck is another difficult decision a linesman is required to make. I believe linespeople generally give the player the benefit of the doubt on super-close foot fault situations. Put differently, players rarely have anything to complain about. Even if they did, they would almost never know when. That’s because they’re focusing intently on producing a high-quality serve while not faulting or double-faulting. Their eyes cannot be on the baseline when they are serving, as the linesperson’s eyes intently are. (In her post-match press conference, Serena conceded, "I'm pretty sure I did. If she called a foot fault, she must have seen a foot fault. I mean, she was doing her job. I'm not going to knock her for not doing her job.") Why do foot faults occur in the first place? Some players with foot fault tendencies simply stand too close to the baseline. Other players suffer from defective swings, errant tosses, or poor balance that induces them to foot fault. At the world-class level, energetic net-rushers, such as foot fault-prone Stefan Edberg – who once foot-faulted 12 times in an Australian Open match – simply bound so quickly into the court that one foot crosses the baseline and touches the court prematurely. Finally, players who rarely foot fault have been known to foot fault late in grueling matches when they are exhausted. That is what some TV analysts see but fail to acknowledge. When Pete Sampras was foot faulted during the fourth set of his shock quarterfinal Davis Cup loss to Spanish clay-court standout Alex Corretja on grass in 2002, the partisan crowd groaned loudly. Captain Patrick McEnroe jumped out of his chair and yelled at veteran Wimbledon referee Alan Mills: “Alan, how many times did they call foot faults [on Sampras] at Wimbledon? Ever?” That, of course, even if true, was irrelevant. After a fifth-set Sampras foot fault, ESPN television analyst MaliVai Washington, the 1996 Wimbledon finalist, emphatically noted, “I’ve never heard foot faults called on him.” To his credit, Washington, alluding to the tremendous pressure in Davis Cup, added, “But it’s kind of funny, the closer a match gets ...” and stressed that he didn’t think the foot fault calls were mistakes. Sampras surprisingly committed 14 double faults and five foot faults, the latter almost certainly a personal record, in what must have been one of his most exasperating defeats. Foot faulting, while nearly always unintentional, is cheating. Just as no self-respecting, honest player would ever want to benefit from a bad line call, he should never want to take unfair advantage of his opponent by foot faulting. And if a player does foot fault, he should expect it to be called whenever he is fortunate enough to have a linesperson on the baseline. Believe it or not, when 1930s German star Gottfried von Cramm was called for foot faults, he thanked the line judge for his diligence. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Paul Fein's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Paul Fein Paul Fein, a USPTA teaching pro and former top 10-ranked New England men’s open player, has won more than 25 writing awards. His 2002 book, Tennis Confidential: Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies, published by Brassey’s, Inc., was listed No. 1 among tennis books by Amazon.com and BN.com. Information about the book and how to order it can be found at www.tennisconfidential.com. His second book, You Can Quote Me on That: Greatest Tennis Quips, Insights, and Zingers, was published by Potomac Books, Inc. (formerly Brassey’s, Inc.) in 2005 and was listed No. 1 among tennis books by Amazon.com and BN.com. For more information, visit www.tennisquotes.com. His third book, Tennis Confidential II: More of Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies, was published April 28, 2008 and was featured on the home page of Amazon.com. |