|

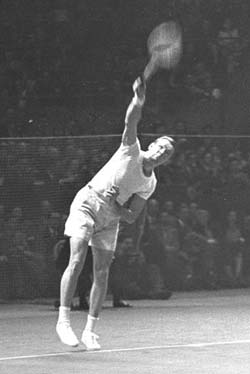

TennisOne Lessons The Serve: A Weapon of Mass Destruction Paul Fein “Pancho gets fifty points on his serve and fifty points on terror. The great champions are always vicious competitors.” −Jack Kramer, on his old rival Pancho Gonzalez. Discussions about the greatest serves in tennis history always start with the devastating delivery of Richard Alonso “Pancho” Gonzalez, a 6’3”, 190-pound strongman with a huge 81” reach. Although he never took a formal tennis lesson in his life, the 1954-61 king of the pro tour was a natural athlete, fortunate to develop his classic motion in the tennis hotbed of Los Angeles. In the June 1960 World Tennis magazine, respected historian Julius Heldman wrote: “The Gonzalez service is a natural action that epitomizes grace, power, control and placement. The top players sigh when they see the smooth, easy action. The toss is no higher than it has to be, and it is timed so that he is fully stretched when he hits the ball. The motion of the backswing blends into the hit and continues into the follow-through without a pause. Pancho is not a heavy spin artist. His first serve is almost flat, and the second has a modicum of slice or roll … just enough for control on second serve.

“The strongest part of Gonzalez’s serve is his ability to put the first ball into play when the chips are down,” continued Heldman. “At 0-40, 15-40 and 30-40, his batting average on first serves must be .950. It is incredible to have so high a percentage while still hitting hard and almost flat. The number of aces served on these important points is also astounding. No other player has so regularly been able to perform this feat, although Budge, for two years, was probably as tough on the serve. Vines could do it on a given day, but not day in and day out.” Like Gonzalez, Pete Sampras was blessed with extraordinary athletic ability and an explosive serve. Three biomechanical features that great servers share are leg drive, high levels of internal shoulder rotation and large wrist flexion, according to Bruce Elliott, the head of the School of Sports Science, Exercise and Health at the University of Western Australia. The Sampras serve exemplified those features with perfection. I consider it the single most lethal shot in tennis history. In his autobiography, A Champion's Mind, Sampras attributed his stunning victories over John McEnroe, Ivan Lendl and Andre Agassi to capture the 1990 U.S. Open title as a callow 19-year-old, to his serve. "I was serving huge – it was like I could hit an ace any time I wanted. To this day, I have a visceral memory of that feeling and rhythm." Dr. Peter Fischer, his early coach, gave Sampras that rhythm and flawless motion along with what "Pistol Pete" called "the loose, whiplash swing" and "the explosive snap." Fischer also taught him how to disguise his serve so opponents could not "read" it. "I learned to use my wrist and I had a talent for 'pronating,' or bending my wrist in a way that enabled me to use the same basic motion to hit different kinds of serves," explained Sampras. "The kick serve was the only one that was a little different, because you have to toss the ball farther back and to the left to get that big kick, and it's impossible to disguise. But even then, I didn't telegraph my intention as much as most players." Indeed, he didn't, because his potent second serve also ignited a serve-volley game that helped him win 14 major titles, including a modern record seven at Wimbledon. "Seven Wimbledon titles in eight years is one of the great achievements in modern sport," noted 1987 Wimbledon champion Pat Cash in the Jan. 30, 2005 The Sunday Times (UK). Praising Sampras' "technical perfection," "huge power" and "supreme physical ability," Cash wrote: "The Sampras serve was the ultimate – unbelievably accurate, supremely forceful and, more often than not, unplayable."

Greats from Yesteryear In Tennis Styles and Stylists, Paul Metzler, the distinguished Australian tennis historian, analyzed the serving versatility of 1920s superstar “Big Bill” Tilden. “He served his cannonball at 124 mph, kicked his American twist sharply, and could curve a sliced service wide and low away from Western [style] players. His mixing of these services, and indeed of all his shots, was judicious, but we must not imagine that his wonderful ball control took the place of speed,” wrote Metzler. "Against 'Little Bill' Johnston he was sometimes forced into restraint and against topspin Japanese players Zenzo Shimizu, Ichiya Kumagae, and Takeichi Harada, he chose to win with slices, but he loved speed. He sometimes held four balls in his hand to serve, and it is said from such a bunch he once banged down four aces to finish off a tournament." Tilden himself touted the American twist in his 1925 classic book, Match Play and the Spin of the Ball. "The American twist, also a reverse as to curve and bound, but far more effective and useful, is one of the greatest assets to a player…. In service, twist rather than speed is the essential point," maintained Tilden. "It is by twist and placement, rather than by speed, that you can force your opponent on the defensive at the opening of the point. Speed alone is easy to handle. Richards, Johnston and Williams, if they can put their racquet on the ball at all, and they usually can, all handle my cannon-ball flat service more easily than either of my spin deliveries." Jack Kramer dominated amateur and then professional tennis from 1946 to 1953 with a high-powered, high-percentage game ignited by his formidable serve. In his 1978 book, Tennis: Myth and Method, Ellsworth Vines wrote: "Although Pancho Gonzalez, Johnny Doeg, Les Stofen and I hit our first delivery slightly harder, no one could match Jack's for pinpoint accuracy.

"Kramer's first delivery had a perfect relaxed motion, precision, and penetrating power, but his second serve was unequalled. His ability to 'spot' it wherever he wanted it with no apparent effort was astounding. For depth, pace and bounce, there never has been anything like it. When he rifled his American twist into the corner, the ball kicked off like a ricocheting bullet (a deep, hard, kick serve to the backhand is the hardest shot in tennis to handle). Kramer had total command of all serves: flat, slice or American twist with endless variations. He was as likely to ace you on a second as on the first, then trip you up by using the kicker as his first delivery on the next point." Bill Tilden praised Gerald Patterson's "tremendous serve, the most perfect style of delivery in the world," in Match Play and the Spin of the Ball. A powerfully built Australian who won a Military Cross for heroism in World War I, the popular Patterson won Wimbledon in 1919 and 1922 thanks largely to his thundering serve, explosive smash (a closely related stroke) and aggressive volleying. In Tennis Styles and Stylists, Metzler wrote: "Patterson's service action, described as perfect, was based on the American twist. For the first serve, he threw the ball straight up above his head and hit it with great strength from his muscular back and shoulders, sometimes as a flat cannonball, but mostly with a little controlling topspin. Action-strip photographs show that in making full use of his height of almost six feet, he reached higher with his right shoulder than other players as he pounded the ball over at full power. With excellent control of curve and placement, his acing became legendary." In his introduction to Ellworth Vines's book, Tennis: Myth and Method, Jack Kramer wrote: "Vines's serve deserves special comment. Budge calls it 'the hardest I ever faced, and that includes Gonzalez.' Vines also had a fine American twist for a second delivery with which to take the net; only von Cramm had a better one. But it was his first serve that was awesome. In one match against Bunny Austin – a superb returner – Vines hit 30 clean aces. Tennis authority Allison Danzig describes Ellsworth's game in these words: 'Vines at the peak of his form could probably have beaten any player who ever lived. His lightning-bolt service was regarded by some as the best of all.' "

The Intimidators So intimidating was 6’4” Goran Ivanisevic’s left-handed serve that in his autobiography OPEN, Andre Agassi recalled thinking before the 1992 Wimbledon final: “I have no chance against Ivanisevic. It’s a middleweight versus a heavyweight.” During the match, Agassi recounted thinking: “As powerful as Ivanisevic’s serve is under normal circumstances, today it’s a work of art. He’s acing me left and right, monster serves that the speed gun clocks at 138 miles an hour. But it’s not just the serve, it’s the trajectory. They land at a 75-degree angle.” Agassi noted optimistically, though, that the match would be decided on a few second serves. As great as the Croat’s serve was, he double-faulted surprisingly often, and Agassi eventually prevailed. “When Goran’s serve was on, it was pretty much unreturnable on grass,” wrote Sampras in his autobiography, A Champion’s Mind. “He was the only guy I played regularly who made me feel like I was at his mercy. I never felt that way against that other Wimbledon icon, Boris Becker.”

Andy Roddick does nothing naturally except serve. He precociously displayed that gift at the 2000 U.S. Open where, as the 18-year-old junior titlist, he smacked a 139 mph serve, the second-fastest in the entire tournament. A year later on the slow clay at the French Open, he belted 37 aces against Michael Chang to break the match record there by eight aces. In 2003 Roddick captured the U.S. Open, his only major title, and in 2004 he set the all-time serve speed record with a 155 mph rocket. Equally astonishing has been Roddick’s consistency for a master blaster. In 2009, he led the ATP Tour in making 70 percent of his first serves How does Roddick achieve such awesome power? “He doesn’t get this power from the abbreviated backswing,” Rick Macci who taught Roddick from age 9 to 14, told The New York Sun. “He’s in and out of the back scratch position faster than anyone in the world.” John Yandell, who quantified the Roddick serve through video analysis, agreed: “I think some of the things that make Andy’s motion are unique to Andy and his phenomenal ability to move the racket that fast…. What you see is a lot of people who are trying to copy Andy’s abbreviated motion and are destroying other elements of the serve.” In other words, the average player should copy Federer’s classic motion rather than Roddick’s. John McEnroe, who captured four U.S. and three Wimbledon crowns, began using his unique closed stance and extremely low back bend to alleviate back problems when he was 18. “Then, as I continued the muscle-loosening exercise every time I served in other matches, I started to notice that I could hit better angles and that people were having a tougher time reading each delivery,” he revealed in the 1982 book, McEnroe: A Rage for Perfection.

Much like a clever baseball pitcher, McEnroe baffled opponents by devilishly varying the spin, speed and placement of his serves. “Several things made John’s serve especially difficult to return,” Chris Lewis, who lost to McEnroe in the 1983 Wimbledon final, told me. “First, his serve was unique, no one came close to serving like him. Second, John’s disguise was such that his set-up and preliminaries suggested he would serve in a particular direction, only to serve in another. “Third, he mixed up his left-handed spins so well with both placement and pace that you never knew what to expect,” continues Lewis. “His superb accuracy enabled him to beat you with either wide serves or body serves equally well. For example, he liked to use a heavily swinging first serve into a right hander’s right hip on the ad side. Rarely did this serve, or any other, end up being in a player’s strike zone. So I was either reaching for something that I couldn’t quite hit solidly, or getting out of the way of something that I found awkward to deal with.” “The Boris Becker serve is humongous,” praised Brad Gilbert, former world No. 4, coach and TV analyst, in his best-selling book, Winning Ugly. “You can’t really get a sense of its weight watching him on TV. It just goes right through you. In addition, if his serve is on, it allows him to take chances with other parts of his game because he knows he can come back with the Heater.” Becker shocked the tennis world when he captured the 1985 Wimbledon as a fearless, 17-year-old wunderkind. “Boom Boom,” a nickname he disliked because of its warlike connotations, bombarded Kevin Curren with 21 aces in the final. In Tennis magazine, 1972 Wimbledon champion Stan Smith analyzed how the power in Becker’s serve “came from a mastery of mechanics and perfect timing. The mechanics that put the boom in Becker’s serve include: a relaxed grip on the racquet, relaxed arms, an upright head, a tossing motion that begins at the shoulder, a deep knee bend, a full shoulder turn and a full extension at contact.”

What distinguishes Roger Federer from past champions, according to U.S. Davis Cup captain Patrick McEnroe, is that “he combines exceptional offense with exceptional defense.” Offensively, Roger Federer possesses the most versatile forehand in tennis history, but his serve ranks a close second among his weapons. When The Mighty Fed collected his record 15th Grand Slam title with a 5-7, 7-6, 7-6, 3-6, 16-14 triumph over Andy Roddick in the enthralling 2009 Wimbledon final, he whacked 50 aces, compared to Roddick’s 24. Last year he finished tied for first with Roddick and Rafael Nadal in second serves points won (57%), and third in service games won (90%). He also tied for third in first serve points won with Roddick and Sam Querrey (79%) and in break points saved with Karlovic (69%). “Roger has the ability to serve where opponents least prefer it,” points out Lewis. “He has an uncanny ability to out-think opponents and surprise them with his clever use of accuracy and variety. He also has those magical hands that can disguise his intentions, making it almost impossible to read his serve.On top of all that, many opponents miss because they're intimidated by the prospect of having to deal with his first shot. He combines beautifully fluid technique with masterful strategy, and that is always a difficult combination to overcome.” The Best of the Rest Sampras had a losing career record (4-5) against Michael Stich, a 6’4” German who upset Boris Becker in the 1991 Wimbledon final. In A Champion’s Mind, Sampras explained why. “Out of all the guys who were real or imagined rivals, Stich was the one who scared me the most. Stich had a huge first serve and a big second serve that he could come in behind confidently, because he was a gifted volleyer,” wrote Sampras. “I always measured guys by the quality of their second serve, and that was the big difference between Stich and the other guys who could hurt me. He had a really, easy, natural service motion, and while the Beckers and Krajiceks and Ivanisevics had days when their second serve was deadly, Stich was the one who seemed able to do it most consistently.”

Greg Rusedski, a 6’4”, 200-pound Canadian who immigrated to England, was essentially a “one-trick pony” who rode his gigantic serve to the 1997 U.S. Open final. There Patrick Rafter, a far better athlete and volleyer, outclassed him. Like most lefties, he was especially dominating in the ad court where he pulled opponents outside the alley with powerful slice serves and then often aced them up the middle. Rusedski, who ranked a career-high No. 4 in 1997, held the men’s serving speed record at 149 m.p.h. until Roddick broke it. Roscoe Tanner, the 1977 Australian Open champion and 1979 Wimbledon finalist (extending Bjorn Borg to five sets), resembled Ivanisevic because of his low toss and extremely fast motion. Also left-handed, the sturdily built Tanner’s serve was once measured (unofficially) at an incredible 153 m.p.h. “Biomechanically, Roscoe’s serve was the most efficient,” noted researcher Vic Braden told Tennis magazine in 1992. Efficient perhaps in terms of sheer power, but it wasn’t the most consistent, because the American, like Ivanisevic, was occasionally plagued by double-faults and a low first-serve percentage. Honorable Mention goes to several other serving stars, such as Australians Geoff Brown, Lew Hoad, Neale Fraser, Mark Philippoussis and John Newcombe, Dutchman Richard Krajicek, France's Yvon Petra, Englishman Mike Sangster, Czechoslovakia's Jaroslav Drobny and Vladimir Zednik, eight-time Grand Slam winner Ivan Lendl, and Americans Bob Falkenburg, Ashe, and Smith. Future Shock

Back in 1991, the late Arthur Ashe predicted no man under six feet tall would ever win Wimbledon again. Since then Ashe has been wrong only once, when 5'11" Lleyton Hewitt easily defeated 5'11" David Nalbandian in the 2002 Wimbledon final. The next year, though, 6'10", 230-pound giant Ivo Karlovic overpowered under-sized Hewitt, the second seed, in the first round. Six years later, Hewitt outlasted the one-dimensional Croat in five sets at the French Open, but not before Karlović blasted 55 aces on the slow red clay to set an ATP Tour and Grand Slam tournament record, breaking Roddick’s tournament record by 18! “The angle he gets, it’s just physically impossible to touch a lot of his serves,” said Hewitt. Karlović, whose fastest official serve is 153 m.p.h., has led the Tour in aces per match for seven straight years, including an amazing 20.7 per match in 2009. Even more amazing, last year he obliterated two all-time records with 78 aces, including 27 in the deciding set, in a Davis Cup match and – you guessed it – still lost against Radek Stepanek, a mere 6’1”, by 6-7, 7-6, 7-6, 6-7, 16-14, on clay no less. After Karlović upset Federer in 2008, the Swiss superstar raved, “His trajectory is unbelievable. He definitely has the best serve in the game. Against nobody do I have to guess on the serve except against Ivo. On top of that, he hits unreturnable serves. Sometimes on the ad side and down the T, if he clocks it on the line, there’s nothing you can do.” Records are made to be broken, but no one could have anticipated the mother of all sports marathons at the 2010 Wimbledon where American John Isner outlasted Frenchman Nicolas Mahut by the unimaginable score of 6-4, 3-6, 6-7, 7-6, 70-68. Super serving produced 168 consecutive service holds and seemingly unbreakable records galore. Isner, built like an NBA power forward at 6’9” and 245 pounds, blasted a phenomenal 113 aces, while Mahut also zoomed past Karlović’s short-lived, previous high with 103. Their combined 216 aces more than doubled the former match record of 96 established by Stepanek and Karlović. In the deciding set alone, Isner smacked an incredible 84 aces to more than triple the old record! McEnroe, now a TV tennis analyst, marveled: “Isner is already among the all-time great servers, like Sampras, Becker and Ivanisevic.” Now, more than ever, height and might make right in serving. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Paul Fein's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Paul Fein Paul Fein has received more than 25 writing awards and authored three books, Tennis Confidential: Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies, You Can Quote Me on That: Greatest Tennis Quips, Insights, and Zingers, and Tennis Confidential II: More of Today’s Greatest Players, Matches, and Controversies. Fein is also a USPTA-certified teaching pro and coach with a Pro-1 rating, former director of the Springfield (Mass.) Satellite Tournament, a former top 10-ranked men’s open New England tournament player, and currently a No. 1-ranked Super Senior player in New England. |