|

TennisOne Lessons The Arms and Legs Connection Daryl Fisher As tennis players, it is obvious that we can all benefit from making better use of our legs. Foot speed and running endurance can only help. Less obvious, perhaps, is that there is a benefit to using the arms less. Also perhaps less obvious is the connection between the use of our arms and our legs. Good movement with the legs often makes it possible to minimize what the arms must do. If the leg movement is insufficient, however, then the arms must often do more to compensate.

Generally speaking, you will benefit from an ability to move your legs more and your arms less. To help in your understanding of the arms/legs connection, I will be drawing on the concept of simplification, some classic tennis instructions, and the strike zone from baseball. Simplification Every tennis player seems to have the natural inclination to use the arms more than necessary. This is certainly true for beginning players. Beginners swing excessively from the shoulder and do not yet make good use of their torsos and legs in their swings. Interestingly, advanced players generally make better use of their torsos and legs, but many have not learned that they do not need to use their arms as much. In other words, advanced players have learned how to add to their games, but many have not learned how to subtract the unnecessary. For beginner and advanced, not only do we not need to use our arms as much, but in most instances less extraneous motion would in fact help us improve. Using less motion generally means that there is less that can go wrong.

There are so many ways to make more motion than necessary that it is impossible to describe them all. For more information about simplification, see How to Improve Your Tennis Strokes by Simplifying, as well as related videos such as Jim McLennan’s Dead Hands. Fast Feet and Slow Hands The classic tennis instruction to have fast feet and slow hands is an early version of my suggestion to use the arms less and the legs more. This instruction still makes sense for volleys, but in the days of wooden racquets, it was applied to the ground strokes as well. At the heart of the instruction is the use of the legs throughout a stroke to create forward momentum by stepping into a shot as it is struck. The reasoning applies less well with regard to modern ground strokes, however, given that the option of open stances removes the necessity of stepping into every ball. With the open stance, your feet can be barely moving (slow feet) and you can still achieve power (fast hands). At least with regard to the ground strokes, to have the hands moving quickly can often be a good thing. How the hands are made to move quickly is a separate issue. Even with modern ground strokes and the use of open stances, the legs and torso are still the drivers for the vast majority of power that is possible. Swing the Racquet, Not the Arm Another related classic tennis instruction is to “swing the racquet, not the arm.” This particular phrase encourages a player to get the racquet through the air but not by using the arm. This raises the question to players of all levels as to how this can be accomplished, and the answer again is through the use of the legs and the torso. When the legs move, the entire body moves, including the arms.

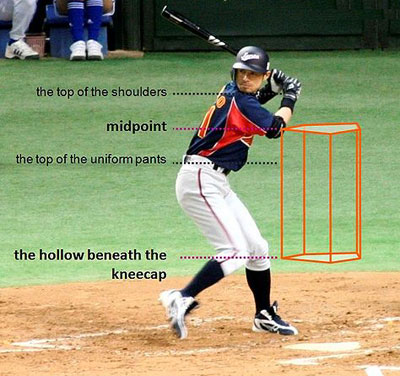

Strike Zone The phrase “strike zone” is borrowed from baseball terminology. If you are familiar with the game of baseball, then the concept of a strike zone should be easy for you. In baseball the strike zone is the area near the batter through which a pitch must pass in order to be counted as a strike. The top of the strike zone is defined in the official rules as a horizontal line at the midpoint between the top of the batter's shoulders and the top of the uniform pants. The bottom of the strike zone is a line at the hollow beneath the kneecap. The right and left boundaries of the strike zone correspond to the edges of home plate The tennis strike zone differs in a few significant ways. First, there is a different strike zone for every stroke. The forehand topspin ground stroke, for example, has a strike zone that is generally about as high as a player’s head and as low as the knees. For a backhand topspin ground stroke, it is about as high as the shoulders and as low as the knees.

Strike zone preferences vary somewhat from player to player, with some grips favoring higher and lower strike zones. The Continental grip for ground strokes, for example, makes hitting lower balls easier and higher balls harder, so the strike zone is generally lower for a player using this grip. The strike zone for tennis also has a component with regard to where the ball should be struck in relation to the body from forward to back. The ball should be struck in front of the body, which means that the strike point is at least somewhat closer to the net than the rest of the body. For more information and clarification with regard to this aspect of the strike zone, see Stable Alignment III: Contact in Front. There is one more important difference between a baseball strike zone and a tennis player’s version of it. In baseball, the pitcher has some incentive to throw the ball through the batter’s strike zone so that a batter does not need to run. In tennis, however, each opponent has incentive to avoid the other’s strike zone, so the strike zone must move to where the ball will be. For this reason, movement becomes a crucial component of success in tennis. Try it Yourself The differences between the baseball and tennis strike zones are less important than the following similarity: a ball that travels through a strike zone is easier to hit than a ball that travels outside of it. In order to achieve the ability to move the arms less, you will need to get the ball through your strike zone on a regular basis.

Go out for a hit for the sake of observing rather than competing. Consider the hit an experiment. While you hit, first do your best to find your strike zones. You should notice that if you meet the ball outside of your strike zone, then your arm is out of position to allow the legs and torso to create leverage. If your legs and torso cannot help you with leverage, you will be required to arm the ball. Arming the ball causes a loss of power and/or control, and often causes hand and arm tension as well. We all arm the ball sometimes because our opponents have forced us into it (and sometimes because we were tired or lazy with our footwork), but of course we would prefer that it not happen regularly. Such shots are desperation shots. We would like to limit our need for desperation shots rather than rely on them to win matches. If you feel the ball is passing through a strike zone but that you are still experiencing hand and arm tension regularly, especially when you are not competing, then your technique (Relaxed Hands and Good Technique) might need some attention before returning to focusing on improving your footwork.

Finally, if you feel like you understand where your strike zones are, your final step in the experimental hit is to apply the concept of reducing what your arms are doing. Do your best to apply one of the classic tennis instructions offered above, and experiment with less arm motion. Just bringing awareness to the ideas through the experimental hit could help considerably. As a general theme, it seems that while many people learn to use their legs and torso as a way to play better tennis, this type of progression often forgets that removing extraneous motions can be a way to improve as well. As another general theme, the ability to regularly reduce the amount of motion from the hands and arms typically requires the simultaneous use of more movement from the legs. You should find that when your legs work sufficiently hard, your arms and hands can just go for the ride. |

|||||||||