|

TennisOne Lessons Andy Murray — In the Head? Adam Gale One of the great things about having a ‘Big Four’ in men’s tennis is that there are six significant rivalries to relish, and they are all appealing in quite different ways. When Federer and Nadal play, it is an epic clash of styles, this baseline age’s answer to Borg-McEnroe or Sampras-Agassi. Nadal and Djokovic wrestle for each and every point, in titanic battles of sweat, muscle, and grit, while matches between Djokovic and Federer have come to be characterized above all by their tremendous unpredictability, as sudden flourishes of clean brilliance from either can turn or clinch the match at any time.

But what of Andy Murray, the junior member of the Big Four, the one many say doesn’t even belong in that exalted category? He’s played his fair share of matches against the others, but his rivalries with them have been diminished by the very predictability of the outcome when they meet. At the majors, Murray is far too often the loser. Some would say that this is simply a question of level, that Murray is not capable of sustaining the tennis necessary to defeat any of the Big Three when they are playing well. Others would say that it is because the Big Three invariably do play well, while Murray often turns up without his A-game to these big matches. I would say that there is some truth to both arguments, and that they are not unrelated. Knowing that the others will surely play very well against him, and that to match them he will have to play more aggressively (i.e. better) than he usually does, creates extra pressure for Murray, which then undermines his performance. It seems to be the same question every year, but could this be about to change? I believe there have been some positive signs in his recent matches against the world number one, Novak Djokovic, particularly in their five-set semi-final thriller at the Australian Open. This match was so impressive and important because both men, not just Djokovic, of whom it is expected, played near their best. Murray, like Djokovic, was able to stand up to the ball, hitting aggressively, deep and on the rise. Like Djokovic, he was able to win points from seemingly doomed positions, in feats of astonishing athleticism and touch. Like Djokovic, Murray seemed to have no weaknesses in his tennis, no holes in his armor or his arsenal. Both players demonstrated what they are capable of: the full and devastating splendor of the modern game.

It is hard to argue that Murray just isn’t good enough to win majors after watching this match. Unlike their final in Melbourne the year before, where Djokovic hammered Murray in straight-sets, this was a clearly a battle of equals. A statistical comparison of these two matches, one year apart, is revealing. On both occasions, Murray’s first serve earned him more free points than Djokovic’s (36.2% of Murray’s deliveries went unreturned in 2011 and 32.1% in 2012, as opposed to 26.4% for Djokovic in 2011 and 23.8% in 2012). On both occasions, the ratio of the two players’ unforced errors was virtually identical, with Murray hitting roughly three for every two struck by Djokovic. When the point was ‘won’ in a rally, however, either by hitting a winner or by forcing an error, the 2012 match was a much closer affair – Djokovic won 65.6% of these rallies in their first major encounter; in their second, this lead had been reduced to 54%. These numbers illuminate what most people watching the matches will already have realized. Though Djokovic retained a slight edge (predominantly attributable, I believe, to the considerable superiority of his forehand down the line), Murray was genuinely in contention this year. Unlike in 2011, this time Murray played well enough to have a chance of winning, and he nearly did. Nearly. Unfortunately for Murray, ‘nearly’ doesn’t cut it in the world of competitive tennis. The fact remains that, despite clearly playing well, he still didn’t win. So why not? The answer, as so often in sports, is to be found in the head. Consider the following data for the 2012 Australian Open semi:

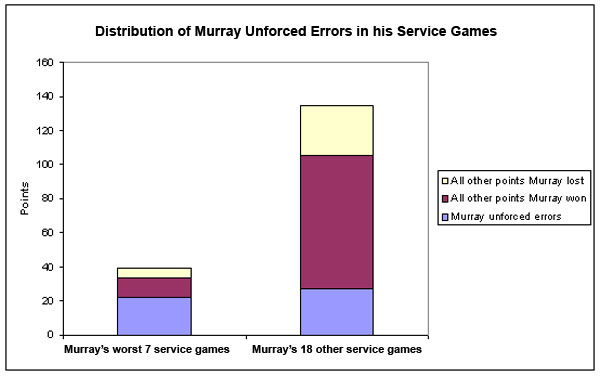

Murray threw in seven very poor games in this match, in which excessive double faults and unforced errors led directly to breaks. Nearly half (22 of 49) of his unforced errors behind serve came in these seven games, which themselves contained only 17 other points. Ignoring these nightmare games, Murray was only broken four more times, primarily as a result of Djokovic’s excellence on return. In contrast, there were only three occasions where Djokovic exhibited very high concentrations of unforced errors behind serve (he committed 9 of his 36 unforced errors in these three games). He, like Murray, was broken another four times primarily because of the quality of his opponent’s play. Effectively, then, the main difference between them in this epic match, at the highest level, was that Murray threw more games away than Djokovic did. To be fair, this did not lead to the Scot losing the deciding set, but it was decisive in his losing the first set and totally took him out of contention in the fourth. This is not a new pattern for the Scot. Often, the disparity in level between him and the Big Three in big matches has concealed the fact that Murray has been the worse match player too. The 2011 Australian Open Final, indeed, is a good example of this — Murray threw in numerous highly error-strewn games then as well. Quite simply, the world number four cannot afford to do this against Djokovic, or Nadal, or Federer. They’re surely hard enough to beat without being given breaks for nothing. Even if he turns up playing at the level he demonstrated in Australia this year — and his recent victory against Djokovic in Dubai and his defeat at the hands of Federer there and against Djokovic in Miami have shown that this level is neither a fluke nor a new constant for him — Murray now faces the obstacle of becoming a better match player.

The tantalizing thing is, the Scot has already shown he is capable of great match play as well as great level, having come back from 2-set deficits on no fewer than six occasions in his career, including twice last year (against Troicki at the French and Haase at the US Open). He just needs to bring great match play against Djokovic, Nadal, and Federer, at the majors, probably more than once. This is his obstacle now. He’s shown he can live with their tennis; he’s shown he can bring this level when it matters; now he has to show he can equal their focus, their wits, and their will to win in the big matches themselves. It might seem sour consolation for Murray to think that, in order to achieve his dream of being a major champion, he must first become a champion in his own mind, finding from somewhere the self-belief that champions have, but it is still possible. It is, after all, exactly what Djokovic himself did. There is no way the world number one would be where he is today, playing the sort of tennis he is today, were it not for the obstacles of Nadal and Federer in his way, forcing him to become better, physically, technically, and mentally. In Djokovic’s case, it was a moment of triumph — he claims it to have been his Davis Cup win at the end of 2010, although I think his saving two match points to edge Federer in their US Open meeting a few months before, after having lost to Federer there for three straight years, was equally important — that flipped the switch and gave him that extra self-belief. Who knows? Perhaps if Murray had been able to take one of those break points late in the fifth set against Djokovic this year, and had gone on to win the match, the same thing would have happened to him. Perhaps. As it is, Murray is still one major title away from where he wants to be, just as he was last year, and the year before that. In some sense, though, he seems closer now. Of course, it is not just a question of waiting for his dream to come true, but of working to make it happen, and the Scot has already demonstrated a willingness to do this. If he keeps at it, and keeps playing consistently at the majors and working at his game and attitude, then the chances will come. Then, it’s just a question of taking them. If he can do that — and I think he really still believes he can — then from a tennis fan’s perspective I can’t wait to see what his rivalries with the Serb, the Spaniard, and the Swiss will become. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Adam Gale's article by emailing us here at TennisOne. |