|

TennisOne Lessons That's the Way the Ball Bounces (two) Jerôme Inen Topspin bounces high, slice bounces low, and balls bounce slower on gravel than on grass or concrete. All these things we think we know about a bouncing tennis ball, however, they won't help us to play better — and that's because none of them are true. Here's everything you wanted to know about the bounce but were afraid to learn. Okay, here is a quick true or false quiz. See how well you do. (Answers are at the bottom of the page).

So, how did you fare? My guess, out of the seven questions, you had one correct answer (I would have, if I had not researched this article!) In this article (a follow-up to a my article, That's the Way the Ball Bounces (Twice…)), I want to explain how knowing the bounce of the ball can help you time your strokes better and make less mistakes. I’ll try to do it in layman’s terms but I can’t entirely avoid delving into scientific territory. I will, however, try to keep it as practical as possible. ‘All’ Bouncing Balls Have Topspin A quick tip: if you are playing an opponent with a mean nasty slice that ‘stays low’. Your reaction — after the first few teeth grinding experiences — is to try to pick up the ball as soon as possible. Don’t. Let the ball bounce. And wait for the ball to come up. Because it will come up!

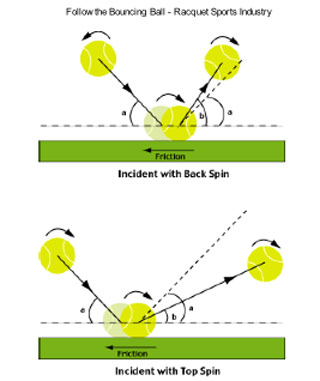

What happens is that a tennis that bounces on a given surface, flattens itself… and the bottom of the ball skids on the ground for a short time (if it’s gravel) or long time (if it’s grass or another slick surface). If the ball that landed was spinning backwards on arrival (underspin), the ‘flattening’ on the ground will reverse the rotation of the ball. The bottom of the ball, as to say, overtakes the top of the ball. If the ball was spinning forward, the top of the ball overtakes the bottom of the ball. The effect is that a ball with slice will bounce away from the ground with a steeper angle than it arrived, (higher) and a ball with topspin will bounce away from the ground with a more shallow angle (lower). So. Slice arrives low, bounces ‘high’. and topspin arrives high and bounces ‘low’. So, if you've been paying attention, you might say, "The question at the beginning of this article was a ruse?" Not exactly. In theory, it is possible to hit two balls, one with topspin and one with slice, that arrive with the same height. But in reality, that won’t happen. You have to hit a slice low over the net, otherwise it will fly long. On the other hand, you want to hit a topspin-ball high over the net; otherwise it will land short or in the net.

What throws off our timing dealing with a slice groundstroke or, exactly the opposite, a kick-serve, is that we anticipate the trajectory of the ball after the bounce as if it’s the same as the trajectory before the bounce. And that is only partly true. A slice-ball will ‘stay’ low, in our perception, because it arrives low. A topspin-ball will jump ‘up’, because it arrives high. This also influences our impression of the ‘speed’ or ‘slowness’ of a court. Grass courts and hard courts are ‘faster’ than gravel, right? Well, the ITF has a special procedure (and a special machine!) with which to test tennis-courts. Basically, they shoot tennis balls at the court at predetermined angle, and then measure how fast the ball bounces, at which angle it bounces, how fast it slows down, and so forth. The results of those tests can be rather surprising. Gravel, for example, takes less speed from the ball after the bounce than grass and hard-courts. The balls on these last courts, however, take less time after the bounce to reach the player. How is that possible? Well, because of the surface, the angle at which the ball bounces on gravel is much steeper than on grass and hard courts. On the latter courts, the ball takes a lower flight. Which takes away time. So the ball flies slower through the air, but wins the race to the player because it has to cover less distance. Can You See the Bounce? The bounce of the ball on your side of the court takes about as long as the contact between the ball and the strings on your racquet, about 0,05 seconds to be precise. The human eye just can’t see events that happen that fast. The truth is even worse, in some ways. Your eyes can’t even see a ball approaching. Your brain tells you that you see a ball approaching from the other side. But in the two seconds or so the ball flies towards you, you actually see about seven or eight ‘snapshots’ of a ball flying through the air. Why? Now I have to explain something complicated, and as I promised, we have to dig into some science, but be assured, it will get practical… pretty soon. Our eyes can follow moving objects if they do not move faster than about three miles per hour. A tennis ball, unfortunately, moves a lot faster. What does the human eye do when stuff happens faster? It basically switches off… and on… and off and on again; like a movie-camera with a very slow shutter. The reason is something called "saccadic suppression". Our eyes jump involuntarily about, when we are watching something. Those jumps are called saccades. We can fix our gaze on an object and we can fix our gaze on an object that moves. But if that object (or person) moves faster than three miles per hour, our brain suppresses our view for about a millisecond. Very short, but still: our eyes are switched off. "Yet that millisecond," as Duane Knudson writes so eloquently in his article The Impact of Vision and Vision Training On Sport Performance, ‘is long enough for a snapshot of the retinal image to be stored, and to enable its further processing. In another quarter of a second, after the image has been processed by the brain, one actually ‘sees’ the freeze-frame image. So perhaps players can see the bounce, if they want to. But maybe they don’t want to. Tennis scientist Howard Brody once calculated that if you want to hit a ball into the court and want it to drop purely because of gravity, the maximum speed is about 80 km/per hour (50 mph). Or, you can say: if you want to hit a ball faster than 80 km/hour, you have to add topspin. For a ball that flies over the net with 108 km/per hour, you have to add a lot of topspin. So let’s assume a situation. Let's say you are 6 meters away from the bounce, of a ball that arrives traveling 80 km/per hour through the air. After the bounce, the ball slows down to about 50 km/per hour (31 mph). That is still 14 meters (42 feet) per second, and the ball only has to cover 6 meters (or 18 feet). Which means you have 0,352 seconds to hit the ball. This is why, after you play tennis for a while, you learn to call a shot ‘in’ or ‘out’ after you’ve hit the ball back, especially with a ball that is fast, like a serve. If you wait to judge the bounce before you hit the ball, you will be too late.

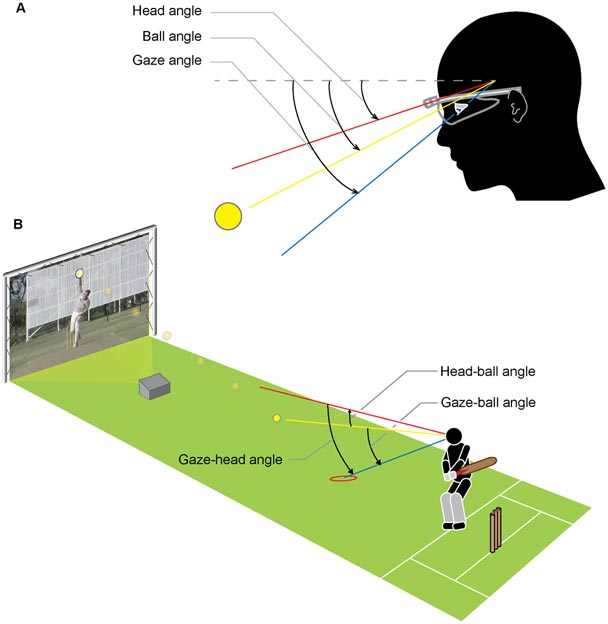

All things considering, it seems a miracle that humans are able at all to hit a tennis ball at all, even if it’s only flying at 31 mph. How do we do it? How do the pro’s hit balls that fly at them with double that speed (or more) we just showed in our simple calculation? The answer is: predicting trajectory. And top-athletes are very, very good at this aspect of hitting, according to research by David Mann, of the Dutch Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam, published in the article The Head Tracks and Gaze Predicts: How the World’s Best Batters Hit a Ball. Mann was curious about the visual strategies of top-batters, because existing research in this field did not study top athletes. Mann and his team examined the eye and head movements of two of the world’s best cricket batters. Not only does his research imply that some sportsmen CAN see the ball on their bat or racquet, but they do something very remarkable with their head and eyes. They don’t look at the ball. They don’t look precisely at the ball. They seem to look in the future! Mann and his team set up an elaborate rig, with a ball-machine, a movie-screen showing a bowler (the pitcher in cricket). Then he took top-bowlers (two of the best 43 guys of 2645 international players since 1877), and a group of amateur-players. He placed a special camera on the head of the subjects, that could measure where the head was pointing, were the eyes were pointing and how the oncoming ball was angled towards the central vision. What was shown in Mann’s research, is that the two elite-batters always had two saccades, the jumps of the eyes mentioned earlier in this article. And get this: the two ‘eye-jumps’ were flying ahead of the actual ball. The first ‘jump’ was to the place where the ball was going to bounce, the second jump was ahead where the bat was going to hit the ball. The amateur-players, in contrast, could only make two of those eye-movements when the ball landed ‘short’, so when it bounced far away from them. If the ball landed closer, they could only get one ‘shot’ of the incoming ball… and a late shot. The amateur-players basically looked at the place the ball had just been, they followed the wake of the ball, while the elite-batters looked at where the ball was going to be. Conclusion If we humans can’t see the actual flight of the ball, and can’t see the bounce and the flight of the bounce (Manns research implies we don’t even want to do so, if we want to be really good), we have to practice predicting the bounce. My advice:

Answers to questions: 1-false, 2-false, 3-false, 4-false, 5-false, 6-false, 7-true Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Jerôme Inen's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

"I’ve learned tennis the traditional, form-oriented way — and it is not the right way! Lijftennis is my attempt to show other people a way to learn quicker, with better results and less frustration. If I have one message: don’t copy others, play and learn from your own body and perspective!" |

|||||||

That seems contra-intuitive. A ball hit with slice stays low, right? Yes, before the bounce…but not after the bounce. Here’s a fact that many tennis players aren't aware of: A ball that bounces after it has gone in a horizontal, parabolic line over the net (which happens a lot with tennis) always has topspin after the bounce… even when they were hit with slice.

That seems contra-intuitive. A ball hit with slice stays low, right? Yes, before the bounce…but not after the bounce. Here’s a fact that many tennis players aren't aware of: A ball that bounces after it has gone in a horizontal, parabolic line over the net (which happens a lot with tennis) always has topspin after the bounce… even when they were hit with slice.

Jerôme Inen of

Jerôme Inen of