|

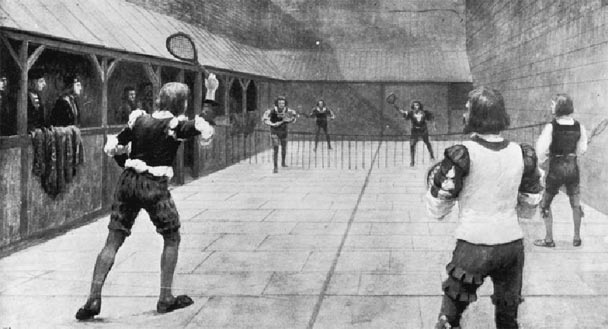

TennisOne Lessons The Damage of Control Jerôme Inen Everyone who read Brad Gilbert's book Winning Ugly will remember this advice: "Hate your mistakes." We all know tennis is a game of mistakes. Even among the best players in the world, matches are usually decided by the player who makes the fewest mistakes and even the winner almost always has more errors than winners. Gilbert also wrote in that same book: "Always ask yourself: who is doing what to whom?" However, that is a line that seems to have less allure, especially among players who work very hard on their strokes. Many fall into the trap of what I call "The damage of control." What do I mean? Lets say a player hits a few double faults too many, or maybe she fluffed several volleys. A couple of shots intended with topspin fly out or over the fence. Typically, the player in question sighs, and goes back to the practice-court to try to eradicate these mistakes. And forgets to ask the question: "What was I trying to do? What was my intent?" Remember, the word tennis comes from the French word: "Tenez!" It means: "Catch" The original players of the proto-game "Real Tennis" used to shout that to each other when serving a ball. It sounds like a warning, but of course it is meant as a kind of rally cry: "TAKE THAT!" So you see, intent!

There are countless examples of the damage of control, but I will describe the damage of control for the serve. If you get my example you can apply the lesson to all of your strokes. The Toss is for the Serve? "When the toss goes, so does the serve." "Without a proper toss, you can't have a good serve." There are million of other sayings like these, and they certainly have a don't run around with scissors in your hand quality to them. Still we all know players who have been playing tennis forever, and are in general, good players. Yet their whole career they have been plagued with toss problems. It can't be a mere lack of talent. There have even been several top pros who have or had problems in this area. Ask a million teaching pros and you'll probably get about a million tips on how to cure a faulty toss. The most important one, I think, and one that actual works, is this one: Shift your weight forward during the toss. Or in the words of Arthur Ashe: "Your weight transfer must start with your ball toss." Now, suppose you take Ashe’s advice to heart. And you start shifting your weight forward while tossing the ball. Most players will do this while partially moving their back foot closer to their front foot. And son-of-a-gun, the ball starts rising to the correct spot — that darned toss actually starts working. But does it? To answer this question, I have to first explore what I meant before when I used the word intent. In an online dictionary I read a nice explanation

Let us keep that in mind. And remember Brad Gilbert’s dictum: "Who is doing what to whom?" You can phrase intent in many ways, you can invent your own definitions, but these are the ones I was taught:

And then a hotly debated one in my quarters (because there is a school of thought that says you can’t train it or should not train it):

One can say that with the three first intents you are trying do to something to your opponent, the least of which is to prevent him or her from taking the initiative. You can do that with five different functions:

Now, let’s go back to the toss. You are bringing your weight forward during the toss, so that the ball goes up to the right place. What is your intent in this case? What is your state of mind? Building; forcing; scoring? With what function do you want to achieve this? Speed? Tempo? Rotation? Disguise?

No, no, you might say. That intent is going to express itself after the toss. Well, that is the problem. Because you’re whole preparation during the serve has not been directed towards the intent, that is doing something to your opponent. The whole ritual has been directed toward getting the toss in the right place! And that is no intent at all! I am not going to ignite again the debate about whether you should move your foot into the pinpoint-stance or if you should use the platform-stance. But it is my theory that a lot of players have poor balance on the serve because their motion is more directed at getting the toss right than to express the intent of doing something to their opponent. To show what I mean, I have a comparison of two players that are very similar in a double way, Venus and Serena Williams. Both are multiple Grand Slam winners, and they are, well,… sisters. Their father, Richard Williams, trained them both. The story goes, he trained their tosses in the living room when the toss was off. He had them toss the ball at a spot on the ceiling. Both move their feet together at the serve. Still their motions are completely different. This is not a slight on Venus Williams, or an attempt to show why Serena’s serve is better. But if you practice to get your toss right and adapt your stroke for it, something gets lost, your intent. Your opponents start to tee off on your serve. In a match, you will notice that. You then start to take more risks with your toss-directed serve to try to hit it with more speed, for example. And it won’t work, because the motion itself is not directed at speed… but at getting the toss in the right place. Hence: double faults creep in. Hence: "The damage of control." Control is Good…If There is a Focus on Intent It is important that while you are practicing or playing a match, to keep an eye on your intentions. We don’t play this game to avoid mistakes, however influential mistakes are in the final outcome. We play this game to create opportunities, to find that inspiring knife-edge between too much and too little which is, just enough. So, the next time you practice your volley, your forehand or any stroke for that matter, think about your intentions. What is it you are trying to do? Is it a forcing shot? A building shot? A scoring shot? Don’t limit yourself to "I did not hit it out." Try to find enjoyment in doing something special with the ball and to communicate with your opponent: TAKE THAT! |