|

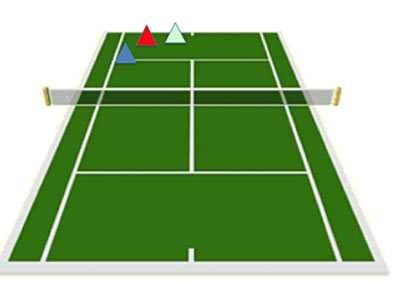

TennisOne Lessons Don't worry, be Fuzzy! Jerôme Inen Suppose you have access to a tennis court and you also have three target cones of different colors: blue, red, green. You put the corners in the forehand corner. The middle, red cone is the ideal target. The blue and green cones are placed left and right of the ideal cone…

Imagine as well, you’ve got two players of equal strength (it would be nice to have twins available, but there you go). Suppose you give each of these two players an assignment. Player 1 has to practice fifteen minutes aiming at the red, middle cone. Player 2 has to aim at the other two cones; not the red one! After these fifteen minutes, you remove the blue and green cones. You place a bet: whoever hits the red cone the most in the next fifteen minutes, wins a box of candy. Who do you suppose will win? The answer may surprise you: it's not player one who wins the candy — not the player who has been aiming at the red cone all along. No, player two, who had been aiming at the targets next to the red cone, will be chewing happily after the session. Don't believe me, try it yourself. Most tennis players (and coaches) will shake their heads in disbelief. They can’t or won’t believe it. Most tennis players are control freaks and worriers. They want control by repetition. They believe that technique should be ‘drilled’ into players (as if tennis players are stubborn soil). ‘Practice makes perfect, repetition makes permanent.’ New techniques should be repeated, repeated, and repeated, ‘until the new strokes become automatic’. The problem is, this idea is flawed thinking — incredibly stubborn flawed thinking. The experiment, with which I just referred to is a classic. It stems from the book Motor learning and performance by Richard Schmidt, and that book was published in 1975… But since then, recent and abundant research has shown again and again: you can learn a motion of the human body by repeating it with specific attention to detail. It does work… However, you can learn that same motion (or technique) better and more effectively by paying less attention to detail. In other words, repeat less and aim at goals that are less precise — goals that are a bit diverse, a little bit vague (fuzzy!). Surprisingly enough You will learn more efficiently! Before I continue, let me formulate what I mean with ‘more efficiently’. My ideal for learning and teaching tennis, is to make you not only better at hitting the ball (with a certain effect or at a certain goal on the court), but also as a player who can use this new competence or ability in matches — under pressure! One of my former coaches once said: ‘Stress is the ultimate lie detector.’ With which he meant: most tennis players fail the lie detector — matches. They practice for months improving a weak stroke: the service, the volley, the smash… They’re able during training to execute their improved stroke… but in matches they will hit numerous double faults, dump volleys into the net, or crush forehands into the next zip code.

"Well, yeah, it's a mental thing," is often the immediate response. But I don’t think so. I think this division between practice and match play is caused by the way tennis players train. To be specific, it is caused by focusing too much on the motion itself (using a lot of repetitions) — an enormous focus on the details of the stroke itself. The odd thing is, every coach will advise his pupils: ‘During a match, don’t think about the execution of the shot.’ But the same coach will train their students to think about the execution of the stroke… because at every lesson or training session he will undoubtedly keep hammering at these very same‘key-ingredients’ of the strokes. But the human body does not learn efficiently by focusing on ‘key-ingredients of movement’. Everything we do – watching, grabbing, walking – is a complex choreography we cannot consciously steer. If we select a goal – the bus stop, the chair in the corner of the room, the sugar jar on the table – we watch and go. We don't think about technique, our body knows how to get there. Fuzzy Logic If you lift a cup of coffee you don’t think: ‘Flex your biceps. Exo-rotate your underarm. Supinate your wrist. Flex your palm. Extend your fingers.’ Still, most tennis instruction is exactly like that: an extensive checklist of movements you have to execute for the ‘perfect’ stroke. ‘Look how Roger Federer drinks his coffee. Imitate him exactly, and you will become as good as a coffee drinker as he is.’ If we taught babies to walk using this method, we'd still be crawling on all fours.

Scientists who try to program robots to perform human movement (walking, grabbing, throwing) have given up decennia ago to make robots do exactly the same as people. It did not work. The only way robots can perform standard human actions, is to program them with fuzzy logic. Wikipedia describes fuzzy logic as ‘vague logics or wooly logics’. The idea that something is ‘true or false’, zero or one, is abandoned. In fuzzy logic, something can be ‘one-third true’. Or, ‘a little true’ Remember the three cones? (There were three cones set up in the beginning of this article.) Well, think about aiming at the three cones, in which cone A (the middle one) is the ‘ideal’ target. The human body works in its own particular way, and learns more quickly to aim at target A by practicing aiming at targets B and C. Fuzzy! Isn’t it? In my earlier tennisone-article Don’t lose your focus, I indicated that extensive research has shown that focusing on an external goal (visual) leads to better results than focusing on an internal goal (at the movement itself). If you ask someone to jump as high as they can, and they focus on a mark on the wall (external focus), they will jump higher than if they focus on the particular movement of their legs or such as (internal focus).

Recent scientific research into all kinds of exercises one could share under ‘external focusing’ has delivered even more fascinating results. People in a broad array of sports (table-tennis, golf, basketball, track, high jumping) perform better under pressure if they train in a non-technical, not at the movement itself directed way. Also, they appear to have to train less than similar athletes who train in a ‘technical’ way to achieve a similar result. They ‘remember’ their lessons better. I don’t want to smother the reader with all the research-papers that are available about this subject. I will give one example of ‘performing under pressure’. The researchers Wenjie Liao & Richard Masters divided 30 beginning table tennis-players in three groups with the aim: learning the topspin-forehand.

After this learning phase, the guinea pigs from each group were told their exploits were extremely weak (yes, that’s mean!) and much worse than the results of the other two groups. Of course every group felt threatened and alarmed by this message. Then they had to hit fifty more topspin-forehands. The group that had received the most explicit instruction (the internal group) scored significantly lower on this next series. The group that learned with the external focus (the triangle in the air) significantly improved their results with the next fifty forehands! But perhaps you might say: ‘But how about the trust you get in your game by repeating the stroke in a precise way? How about rhythm?’ Aah, rhythm. I love that, too. If you play with someone of equal level (or a little better than you), and both of you are so kind to sustain the rally, it is indeed a pleasure. The tennis court becomes a giant drum on which you can make beautiful music, beautiful rhythm. The thing is, in a match, 99 out of 100 times you won’t get rhythm from your opponent. Very seldom do you play a ‘delightful’ match — a match that is logical, in which first one player attacks and then the other player attacks — a match where the speed of the ball is neither too hard nor too soft, where the game flows like a tide that is coming and going. Unfortunately, a tennis match usually is a chaotic affair in which attacking; defending, neutralizing, and constructing points intersect in a fuzzy way. If a tennis match is a musical composition, it is more like Flight of the bumble bee of Rimsky-Korsakov than An die Schöne blauwe Donau of Strauss. So… what’s the right learning-tactic?

First of all you have to concede that you train for matches and that matches will never develop in the controlled way that training sessions develop. Second, you have to acknowledge the fact that endless repetitions of the ideal stroke won’t result in the ideal stroke. Third, you have to find exercises that train your technique with creative, external (meaning visual) cues and targets. Four: start loving the ‘right’ mistakes. Stop worrying about control in your practice sessions! The exercise with the three cones is one way. But you can apply fuzziness in more aspects than ‘aim’. Take topspin, for example: the effect of forward rotation. Most players train this by repeating the stroke with the same effect: a very high bouncing ball. I don’t like to use famous players as an example, but let’s go: if Roger Federer practices topspin, he does not only try to make ball bounce high and far… he also tries to make the ball bounce twice in a few yards! We ordinary mortals probably can’t repeat that. But we can try to make the ball bounce in funny ways. To the side, straightforward, slow forward. Or, as a ‘right mistake’: hit the ball with so much topspin that, on purpose, the ball flies into the night. And laugh about it when you achieve it. Fuzzy training means: give up the control of the ideal stroke. Dutch tennis coach and writer Martin Simek once said to me: ‘The best thing would be, to learn to play tennis on a court without lines. First you learn to hit. Then you learn what to do with it.’ It’s an idea you could use for learning new technique. For example: do you want to add speed to your serve? Practice serving right into the fence on the other side of the court as hard as you can. If you can do that, all you have to do, is toss the ball further in front to get it ‘in’. Want to master a kick-service? Don’t dwell too long on the use of your legs or the pronation of your forearm. Suspend a line seven feet over the net and try to serve over the line and into the court. Another exercise: walk around the court and serve from several positions. From the service line. From the left, from the right. From the back fence. See if you can hit the ball close to the service box from anywhere. You can invent a lot of exercises yourself. Position yourself in the wrong way for the ball, on purpose. Try to hit a shot off balance, to use the ‘wrong’ grip. Look for the kind of trouble you want to conquer in matches. You give up control to create freedom for your body to discover. Anything to give your body a broad, fuzzy knowledge: this is the way it works. Don’t’ Worry, be Fuzzy!

Sources If you really want to delve deep into this subject, here a list of scientific sources. With grateful regards to Berry DC & Broadbent DE (1986). The combination of explicit and implicit learning processes in task control. Psychological Research, 49. Masters RSW (1992). Knowledge, nerves and know-how. The role of explicit versus implicit knowledge in the breakdown of a complex motor skill under pressure. British Journal of Psychology, 83, 343-358. Masters RSW (2000). Theoretical aspects of implicit learning in sport. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 31, 530–541. Liao CM & Masters RSW (2001). Analogy learning: A means to implicit motor learning. Journal of Sports Sciences, 19, 307-319. Lam WK, Maxwell JP & Masters RSW (2009). Analogy learning and the performance of motor skills under pressure. Journal of Sports and Exercise Psychology, 31, 337-357. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Jerôme Inen's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

"I’ve learned tennis the traditional, form-oriented way — and it is not the right way! Lijftennis is my attempt to show other people a way to learn quicker, with better results and less frustration. If I have one message: don’t copy others, play and learn from your own body and perspective!" |

Jerôme Inen of

Jerôme Inen of