|

TennisOne Lessons Get-Goals and Grow-Goals Jerôme Inen Why do so few top-juniors achieve top-results at the professional level? The evidence suggests that top-juniors often choose for Get-Goals instead of Grow-Goals — which they should have done. Players — juniors or other developing players should aim for "the chance of great success" instead of "the greatest chance of success." Everyone says… You have a daughter who plays tennis. Let us say she is thirteen years old. Everyone says she is a great talent, perhaps the biggest talent your country has at this moment. She is that good, the national tennis-federation pays everything: her coaching, her travels, rackets, shoes. The federation has offered also to take care of her coaching, but you and your child are very happy with her current coach, who trains her since she was a mere six. He’s actually a pediatrician and a tennis-coach, which makes you feel comfortable about entrusting your child to him. Then the coach does something weird. Your daughter has an excellent double-handed backhand. Or used to have. From one day to another, her coach tells her to hit her backhand with one hand. And not only that: your daughter is a killer from the baseline. Now she has to run to the net on every instance. Prompted, her coach says, calmly: ‘This is the best for her, in the long run. She is going to be very tall when she is an adult. She must adapt her game now for the future.’ Your daughter used to win all the time, now she starts to lose. Also: always. For one long year, she does not win matches — at all. She says her new backhand stinks. She begs her coach to hit her two-hander again, to be allowed to stay at the baseline. Everyone attacks the coach; everyone says you should take your girl away from him. What would you do? This is not an invented story. It is, actually, almost entirely true. Except that the girl was a boy, he came from the United States. His name was Pete Sampras, his coach the pediatrician Peter Fischer.

Sampras was famed in his youth as the biggest talent of the United States, perhaps the biggest ever. He used to play primarily from the baseline and with a two handed backhand. When his coach Fischer changed his backhand and ordered Pete to start playing serve & volley, the flak came from all directions. Every time Fischer said: "Pete wants to win Wimbledon. He should play now like he has to play as an adult. Even if he loses now, all the time." Well, we know all how it worked out. We had to wait for a while, and even when Sampras went to the pros we had to wait. André Agassi, his later great rival, wrote in Open, his autobiography that Pete could not keep the ball in court when he started out as a pro. But revenge is a dish that is best served cold. Sampras in the end won 14 Grand-Slam titles, including seven Wimbledon-titles. One should remember Sampras’ story when we think and talk about "big talents." Sampras is an exceptional talent, but his story is as exceptional as you think. If one studies multiple Grand Slam-winners, one will see that these players in their development chose for grow-goals instead of get-goals… which most talented players are prone to do, to their own detriment. Most people see development as a straight route, a linear development. You start at level 1, then you progress to 2, 3, 4, and if you are talented, all the way to the top. If it doesn’t work this way (and it usually doesn’t), people get angry and resentful… about themselves… and about others. This is clearly demonstrated when there is a big tournament in which your compatriots are eliminated in an early stage. In my country, alas, this is often the case at the moment. At the recent ABN-Amro-tournament in Rotterdam (won by Roger Federer), the bitterness dripped from the media. Robin Haase, Thimo de Bakker, and Igor Sijsling lost in the first or second rounds.

What fired up the resentment against these players was that De Bakker, Haase, and Sijsling were very successful juniors. De Bakker was number 1 in the juniors, even. The comment was: ‘The talent is there. Why does he do so little with it?’ The answers the experts give at these questions often look like accusations. At the moment, it is always a general wisdom that Dutch tennis players have "the wrong mental state" or "the wrong attitude." Christopher Delavaut recently wrote an article on TennisOne about players that, according to him, had all the shots but not the success that belonged to those shots (Raw talent is not enough, march 2012). He was amazed at the practice courts by players who looked like the real deal, but actually were just inside the top-100, and usually lose in the first round of big tournaments. In his elaborate explanation, Delavaut looks for explanations in the mental aspect of the game. He writes, for example, about "the talent flaw": very talented players who are cursed by their talent, because they never had to work really hard for results in their junior years. Well, what does go wrong with players who are number 1 at the juniors (until 18 years old) and who turn pro? Do they all lack the killer instinct?

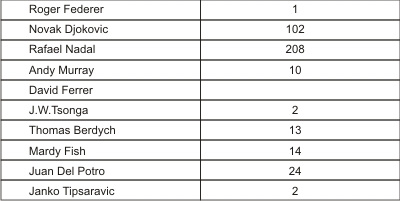

I don’t think so. One of my hobbies is collecting old books about sports. Years ago I was fascinated by a list of players who once won the junior-Grand Slam-titles: Rolland Garros, Australia, Wimbledon, and the US Open. Sometimes I recognized their names. Most of them I had never heard of… and I am a tennis buff. Not only did only a couple of those boys and girls win a Grand Slam-tournament (Edberg, Sabatini as the exceptions), most of those players never even won a ATP-title… For my oncoming book and website Lijftennis, play from your own perspective, I asked the ITF (the Internationale Tennis Federation) the yearend rankings for juniors between 1998 and 2011. I was curious to see if in the current times, the trend I saw in my old books had continued. It has. 1998 and 2011, those are 28 number one players of the boys and girls. Guess how many of them have won Grand Slam-tournaments by now? Half? A third? Nope. Three! Roger Federer, Andy Roddick and Svetlana Kutznetsova. Of those 28 numbers one only seven reached the top 10 at the pros. It is amazing to watch those top juniors through the years. Some names we know, but of most of them you got to think: "I’ve never even heard of them. Where have they gone?"

As a labor of love, I took the top-10 juniors of 1998 until 2002 in a database. Then I added to the database their highest ranking at the ATP-tour, at the big boys. The average ranking those top 10 boys get? 145… Another analysis: I took the top 20 girls and boys from the period 1998 until 2003, and calculated what how they fared in the pro-circuit. How many of them reached the top-100? The girls have a fairly good chance in that aspect: 69 percent of the top-20 girls reached the top-100 of the WTA-circuit. The boys have to be more pessimistic: more than half (52 percent) did not make the top-100 on the ATP-tour. (End-date of the survey: november 2011).

Of course there are some problems with this list. Nadal's humble position is partly caused by the fact that the Spanish federation organizes a lot of tournaments for boys that do not count for the international ITF-list. But still… So what is happening here? One has to realize that the number 1 at the junior-level is not the biggest talent there is at that moment (as is often assumed). They are the best match players of their age group. That is something else entirely. They have achieved their Get-goals of the year: becoming number 1 (or some high ranking) at the ITF-list. But getting a Get-goal is something different than their Grow-goal: to able to play in such a manner that you make it on the ATP-tour. One can watch juniors from the common denominator — most of the juniors — or from the exceptions. And if one watched most of them (Roger Federer the exception), most of them surprised us when they turned pro in some way or another. I am talking about players like Rod Laver, Bjorn Börg, John McEnroe, Boris Becker, Mats Wilander, Pete Sampras, Venus and Serena Williams… and in the Netherlands: Richard Krajicek. Get-Goals What do these players have in common? All of these players, somewhere in their development chose for Grow-goals instead of Get-Goals. They changed a stroke or style… dramatically. And later they reaped the benefits — often exactly the stroke they changed earlier in their development.

To explain further what Get-goals are: they have to do with the short and mid-short future. If you are a talent in your country, and you want to make a career out of tennis, you need money. Lots of money. You can get money from sponsors, from national federations. How do you convince them? By success, by showing your talent. So you have to win. Not in three years, not in a couple of months. But next week, tomorrow, today, now! John Newcombe, multiple Grand Slam-winner, summarized the dilemma very well in an interview with Tennisassist in 2009: "There’s so much emphasis today on points and if you accumulate the points you get a ranking, and if you have a top ranking as a young junior you get selected in teams to go away and stuff like that. So there’s just not enough emphasis on developing the foundation of your game. I like to look at it, if you’re building a house, you want to build the foundations of that house so strong that if a cyclone comes along it won’t be able to knock that house over." A prime example, says Newcombe, is the volley. There are very few top players who dare to play serve and volley, or dare to volley a lot. Newcombe: "All these players today mainly, because of the racquet equipment they use, they hit the ball so well off the forehand and backhand that at 11 or 12 years of age you come to the net, you’re just going to get passed or they’re going to hit topspin lobs over your head." And, like Newcombe said, then your ranking is threatened… The solution, according to Newcombe, is choosing for the long view — and not for the short term solution. "So I think that if you want to develop a young player who’s going to have great volleys take him out of tournaments at certain times as they’re developing their games at a young age, and just work on their net game: how to move around the net, how to volley." Grow-Goals

Newcombe talks about Grow-goals (instead of Get-Goals). What are they? Grow-goals are not about winning per se, but about levels you want to achieve. How do you need to play to win not at the level where you are, but at the level you want to be? How do you have to play to win against that player to have a chance? In what aspects do I already achieve that level? And in which ways do I not achieve that level? What kind of competence do I need to achieve that level? I've already talked about Sampras. What about the Williams-sisters, Serena and Venus. They didn’t play junior tournaments. Their father made them practice against much older female opponents and a lot against men. Only when they reached the level Richard Williams thought they needed, then he let them play matches. Everyone knows the result: 21 Grand Slam-titles in singles (and another heap in doubles). Then there’s Rafael Nadal. Eight years old, he won a tournament for under-12. His uncle and coach, Toni Nadal, encouraged him to play his forehand with his left hand. You are reading this right: Nadal originally was right-handed!

Another example of stunning decisions (with a big reward) from my home country The Netherlands: Richard Krajicek. He was already the number 1 of the Netherlands in the fourteen and under, playing a steady game from the baseline with a double-handed backhand, when his coach, Cees Houweling advised him (just as Sampras was advised): "Learn to hit your backhand with one hand. And develop yourself into a serve and volley player. You’re going to six feet three, you won’t have a chance as a defensive baseliner then." Between 15 and 17, as a junior, Krajicek disappeared under the radar. In the beginning of his pro-career every opponent knew: Richard’s backhand is his weak side. Until Krajicek humiliated Pete Sampras at Wimbledon in 1996 — especially with his backhand. He won Wimbledon that year. This all shows: hard-nosed decisions, with a vision of the far future, ultimately reap the biggest success. Not the biggest chance of often success… the biggest chance of big success! Are there lessons to be learned? For the juniors, I think less fixation on rankings is needed. Coaches — as John Newcombe suggested — need to dare to take their pupils out of competition sometimes… or allow them to lose their ranking. Further: one can watch how the top-players play now, and then think: ‘Right. That means I have to play tennis that way too.’ But for young players (and others) it’s better to think: how will the players of the future play?

Another important issue: in my home country the federations for different sports — hockey, soccer, tennis — compete with each other for talent. Some federations have rules that make it near impossible for children to be active in two sports. That is detrimental for the broad development of tennis, but also for all kinds of sports. Children and youngsters need to be stimulated to do several sports next to each other. Is there a lesson here for the non-parents of the readers, for their own game? I gather that you frequent this website because you want to improve your game. Perhaps you want to reach a higher ranking. If you win a lot of matches at this moment, don’t change much! But, but, but… if you are someone who looks further than that… Suppose you not only want to reach one ranking higher, but in five years, you want to be two ratings higher up? Then there are real choices to be made. You have to start playing against much better players, of the class and rating you want to reach. What happens in those matches or practice-matches? Do you need to sharpen your game? Of do you have to change it? Do you need new capabilities?

In that case, you have to dare to choose. Either you proceed as you are doing now, and your results will be the same. Or you chose for change. You will have to try new strokes and tactics in matches. You probably are going to lose matches you could have won, if you would have played "normally." What is it going to be? Get-Goals? Or Grow-Goals? It could be, for growth, you have to go to the net more often. Play closer to the baseline. Have to work on your conditioning. Try to mess with your opponents’ game by messing with your own game. In all these instances, you will have to step out of your comfort zone — that nice spot on the court you have dug for yourself . It will hurt a bit. But growth without changing — it just doesn’t happen.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Jerôme Inen's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

"I’ve learned tennis the traditional, form-oriented way — and it is not the right way! Lijftennis is my attempt to show other people a way to learn quicker, with better results and less frustration. If I have one message: don’t copy others, play and learn from your own body and perspective!" |

Jerôme Inen of

Jerôme Inen of