|

TennisOne Lessons It's Not All in the Head (It's About Game Too) Jerôme Inen If you convince yourself that most of your game — good or bad — is decided by your mental state, you will drive yourself truly "mental." And you deny yourself the possibility to analyze and improve your game. Finally, summer is really here. This period of the year is also the first moment of reflection on your game, and that of others. What came true of your expectations? Which friends played better than you expected and who played worse? Which pro-players surprised us and which one disappointed? In all those conversations, one word rings back and forth like an echo in an empty church …"mental." Your friend John losing most of his matches this year, while he won almost everything last year? "It is a mental thing." Your teammate Diane suddenly on a winning streak? "She has grown, mentally." Tsonga beating Federer at the French but losing meekly to David Ferrer? Mentally, he could not muster it.

During a broadcast about the Queens Club tournament, former number 1 Lleyton Hewitt reached the semi-finals, beating two top-20 players on the way. Explanation? Most veered towards his diehard attitude. Talking about Hewitt, I heard one esteemed British commentator, a former tourplayer say: "I think the game is about ten percent strokes and about ninety percent head.” I bet most of you will now nod sagely. Of course, strokes are important. We all work hard to improve them. But still, most tennis players feel – and this goes for amateurs as well as pro"s – if they were mentally as tough as nails, like Rafael Nadal or Björn Borg before him, they would win a lot of matches they now lose. But… is that really true? Of course, having the concentration and imperturbability of a zen-buddhist would help. But do we really miss that crucial second serve, that high forehand volley, or that sitter-smash because of our mental state? Do we have a mental problem because we lose to a player with a lower ranking? Or have we just had a "mental breakthrough" because we beat someone to whom we are supposed to lose to? In this article I want to offer three possible explanations for "surprise" losses (or victories), that you can use for analysis of others, but more importantly, for yourself. If you attribute too many of your achievements, good or bad, to the mental aspect, you deny yourself the possibility to analyze and improve your game. The areas I will focus on are "match-up," "money-ball," and "regression to the mean." Match-Up VS. Rankings Where you are on the scale — as a pro on the world-rankings, as an amateur on a range between 6.0 and 1.0 — is often seen as a razor-sharp division. Though it’s true that a 6.0 player will beat a 5.0 player 99 out of a 100 times, the differences between players of about the same level, is not so clear cut. The Australian Hewitt was ranked 82 before he began at the Queens club-tournament, yet he managed to beat no.19 Sam Querrey and no.8 Juan Del Potro. "Hewitt is just excellent at grass," the pundits said, but at the same time these same pundits seemed rather puzzled. Carl Bialik of The Wall Street Journal wrote an excellent article about Hewitt, called "Lleyton Hewitt: Lethal on the Lawns."In it he explained that Hewitt’s winning percentage on grass (70 percent) as a Top-100’ish player is about the same winning percentage he recorded in 2009 when he was much higher on the world’s ranking (74 percent). Hewitt basis most of his success on grass on his footwork. The author thinks Hewitt’s straight, no-loop groundstrokes are as much an asset on low-bounding courts as they are a liability on other surfaces. If that is the case, or both, the fact remains: a match-up is always between one player and another, and the surface they are playing on. Here’s a nice trivia-question. Against which player does Pete Sampras, former number 1, winner of 14 Grand Slam-titles, have a losing record? Boris Becker? Agassi? No. McEnroe? Nope. The answer is Richard Krajicek, winner of 1 Grand-Slam title. My compatriot has the edge: 6-4. And you know who gets a draw of 2-2 against Sampras? My other compatriot Jacco Elthing, despite the fact that his highest ranking was 19 in the world. Some players have something that doesn’t bother player "A," but derails the game of player "B," regardless of what their prospective rankings are. At the French Open, Jo-Wilfred Tsonga beat Roger Federer (number 3 in the world) and then lost in straight sets to David Ferrer (number 4). Would Ferrer have had a chance against the man who was beaten by Tsonga; Federer? I doubt it. Ferrer is 0 and 14 against Roger Federer. And that includes matches played on clay also. The official Rolland Garros site wrote about the Tsonga-Ferrer match: "Tsonga was a shadow of the man who had cruised through the earlier rounds. He seemed agitated, irritated (literally emptying water bottles into his eyes mid-way through the match) and mentally perturbed."

Money-Ball Tsonga said himself of the match: "The plan was to be aggressive and control the baseline, but he defended well and I felt like I always had to play the perfect shot to put him out of position. He was even faster than usual, destabilizing me." The Frenchman felt as puzzled by the match, as were the fans and experts on the side-lines. And that is because, in my view, matches are mostly analyzed in the wrong way. During broadcasts all kinds of analyses appear on TV — first service percentages, return-percentages, forced and unforced-errors and so forth. All very interesting …but it says nothing of the match-up between the two players who are playing! For example, it would be much more telling to see how Tsonga, during his whole career, has scored on the second serve of ALL of his opponents (47 percent), how much he scores in the match against Ferrer we were watching (34 percent), and how he has scored against Ferrer’s second serve in all the matches they played against each other (35 percent). This statistic shows that Tsonga, as regards to his return on the second serves, played a very typical match against David Ferrer. The match-up between Ferrer and Tsonga means that Ferrer wins about 32 of the 50 second serves he hits. That is probably why Ferrer in ATP-matches is 3-1 up against Tsonga… One could say that Ferrer's second serve is one of his "money-balls" against the Frenchman. (What is remarkable is that Tsonga, in his career, has had a much better return-of- second serve percentage against Rafael Nadal: 47 percent).

The website, mindtheracket.com, recently suggested in a blog that tennis needs a "money-ball" revolution, much like what has happened in baseball. Meaning that in tennis there is a treasure of meaningful statistics to be had… if you use the stats in the proper way. Take the often quoted as important first service percentage. Who leads the ATP tour in 2013? Roberto Bautista Agut. Surprised? How about aces? That's Nicolas Amalgro. Well at least we've heard of him! Okay, first service points won? Amalgro again. Points won on the return on the second serve? Number 1: David Ferrer, number 2 Novak Djokovic. Now it is getting familiar! It is my estimation that if experts would use these stats in another way, they would come up with much better predictions for matches than they do now. Currently these prognosticators go by rankings or the form of the player during the tournament (see the example of Tsonga). And some stats are sorely missing. How about average speed of the ball during rallies or tempo (meaning: how fast, on average, does a certain player hit the ball after the bounce?)? How do players match-up in these areas? Perhaps David Ferrer plays in a much lower tempo than Tsonga and Federer, which hurts him if he plays against the Swiss, but from which he reaps the benefits against Tsonga. Who knows? It would be fascinating to at least record the stats. At the amateur and recreational levels, compiling stats is harder (we don’t all have full-time statisticians at our service). However, there it is also unwise to succumb too fast to the "mental problem." Does your forehand go awry for no reason at all from one match to another? I don’t think so. If your forehand went well against player A, but much less so against player B, the second player is probably doing something different than player A! Regression to the Mean In my opinion, most amateur-players have a dismal estimation of what their money-ball is, (and consequently how they match-up against certain opponents). The result is that often what they experience as an off-day is actually "regression to the mean." Let me explain that. Imagine a player who hits about three or four double faults per match. During a tournament, he plays four two-set matches. He hits no double faults the first match. Great! The next match he hits two double faults. Still pretty good. The next match he hits three. Oh dear! In his next match, which he loses, he hits eight double faults. His analysis: ‘During the tournament, the double faults crept up… My serve let me down.’ The first thing is: perhaps he did not lose at all because of those double faults. Perhaps he hit much too many returns of second serves into the net. But more importantly: if you look at the double faults average during the tournament you will come to 3,2 double faults per match, which, for this player, is about average.

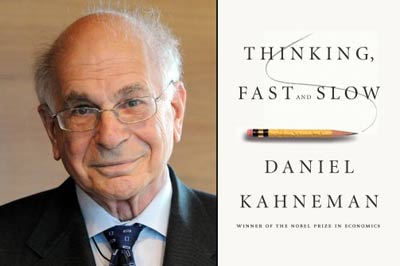

This fallacy is typical of the thinking ‘fast’ (and sloppy) that Nobel prize-winning psychologist Daniel Kahneman describes in his book Thinking, fast and slow. We think that one stat — say the performance of a players serve — is meaningful. While a particularly good day could be plain luck… and a particularly bad day could be plain bad luck. Look at the “Sports Illustrated jinx,” says Kahneman. There is an idea that an athlete whose picture appears on the cover of the magazine will be jinxed. The season after the appearance on the cover, the athlete seems to go through a slump. Not so, according to Kahneman. "An athlete who gets to be on the cover of Sports Illustrated must have performed exceptionally well in the preceding season, probably with the assistance of a nudge from luck — and luck is fickle." The slump is not a fall into the abyss, it is a regression… back to the true level of the athlete in question. Take the earlier example of the Ferrer-Tsonga-match and the percentage of Tsonga's winning points on the Ferrer-second serve. In the four ATP matches these players met, the percentages were: 36 - 40 - 32 - 34. So Tsonga had two matches in which he scored higher than his average, one of which significantly higher. Than one lower than his average. And one almost his average of 35. Putting It All Together Of course the Match-up, the Moneyball, and the Regression to the Mean are all connected. If your big weapon is the inside-out forehand, but you play a match against a player who’s moneyball is the backhand down the line… the match-up for you may not be so good. Don’t expect a day where you can dominate with your forehand. Ask yourself three questions before or after a match:

If all those questions can be answered, then perhaps, we can ask ourselves: was this loss, or this win really ‘mental’?

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Jerôme Inen's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

"I"ve learned tennis the traditional, form-oriented way — and it is not the right way! Lijftennis is my attempt to show other people a way to learn quicker, with better results and less frustration. If I have one message: don"t copy others, play and learn from your own body and perspective!" |

||||||||

Jerôme Inen of

Jerôme Inen of