|

TennisOne Lessons Fabrice Santoro – The “Magician” Jim McLennan I was first captured by the style and grace of Fabrice Santoro at the 1999 US Open. Wandering the grounds, I came upon his early round match against Jan Michael Gambill in Louis Armstrong Stadium (which truly had and has such a better feel than the cavernous Arthur Ashe Stadium – but that is another story). Santoro played unlike any modern player I had seen (though he did remind me of a NorCal wizard named Whitney Reed), for his game was all about deception, misdirection, change of pace and spin, defense, court movement and guile.

Gambill would pound away with great effort and exertion, and much like an aikido master who captures and redirects the force of an opponent's blow, Santoro would deflect the ball at often bizarre angles and places. As the match wore on, a fatiguing Gambill contrasted entirely with the much fresher if not playful Santoro. At four all in the fifth, Gambill succumbed to cramps when serving, stroked two balls wildly into the stands and then conceded defeat. But not at all graciously, for in the post match interview I believe he complained about being “slimed” by Santoro. Perhaps something similar is felt by the aggressor who winds up on his back from the subtle redirection of force of an aikido master. Fabrice Santoro is 33 and turned pro in 1989. He has won $7,628,281 in prize money while capturing four singles titles and 18 doubles titles, including two grand slam titles at the Australian Open in 2003 and 2004. In the 2005 US Open, he played Federer to three close and captivating sets, losing 5-7, 5-,7 6-7. If any of you saw that match, you had have been entertained by the shot making, but equally their respect for one another’s skills, and unusually by their own enjoyment of many of the points, which concluded with either or both of them smiling. Click here to view Fabrice Santoro in T1 Super Slow-Mo™ Video In Monte Carlo, 1998, Santoro thoroughly dismantled Pete Sampras 6-,1 6-1, and though clay may never have been Pete’s preferred surface, that is as an unusual a drubbing as Pete may have ever endured. I have read that in post match comments, Pete labeled Fabrice “The Magician” but somehow I imagine that nickname arose far earlier on the French clay courts as Fabrice was moving up the ranks. As I watched him in New York, and continued to follow him either in person or on TV whenever possible, what is most unusual about his game is his forehand. Always struck with underspin, this right handed player hits with two hands but follows through with his left hand. This may be said again, two handed forehand with a left handed follow through. Always underspin, but varying spin and speed between drives, floaters, and “droppers.” Further, he waits to “declare” his shot, such that many of the normal cues opponents use to get a jump on the ball are just not evident with Santoro’s shots.

I believe that in many baseline exchanges, the men and women are actually cheating ever so slightly, moving just before the opponent hits, anticipating the direction of the ball, thereby getting there either earlier or with just the slightest bit less effort. Certainly many of the big but not particularly creative players, indulge in monotonous baseline rallies with little change of direction or pace, and in those instances both players seem to get to most everything because there are so few options for them to anticipate. The Drive This situation is turned on its head with Santoro. His wide range of shot making as well as his unpredictability routinely denies an opponent an early start. So even though Fabrice relies more on ball control than sheer power, his disguise adds value to his off speed but carefully placed shots. In this first three frame sequence we see the classic Santoro forehand. Preparation is quite high, with an open face. But at this moment there is no indication whether this will be a drive, a floater, a crosscourt, a down the line, or even a drop shot. There is no chance to anticipate or start early, the opponent is simply waiting, waiting, waiting for the “knife.” At impact the racquet is square to the ball, but still it is hard to see whether this will be a drive or drop. Only on the follow through can I discern that he has stroked the ball sharply down the line with a magical version of backspin and sidespin.

If you had started to move forward anticipating a drop shot, then this ball will land behind you in the corner. If you waited just a moment too long to decide where it was going, you will be late. And if you do get to the ball and simply return it (as occurred in this sequence) you are then faced with the next shot and all its possibilities. The Drop Shot Sequence 2 shows the concluding shot of the rally, a wicked cross court drop shot that the opponent retrieved but could not control, driving it long to Fabrice’s backhand corner. Note again the preparation, nearly identical to the down the line sidespin drive. At this moment there is no way to anticipate, no chance to get a jump on the ball, no way to start early. Impact is again nearly identical to the drive. The racquet is square to the ball on a sharply vertical descent. But at the impact event, and we can see this only on the follow through, Santoro adjusts his hands to spin rather than drive the ball, and to direct this shot crosscourt. Somehow I know he enjoys this process, he is truly the Cat and the opponent the mouse, and the amount of running that occurs (that Gambill discovered but I suspect Sampras was disinclined to do) is just overwhelming. And in as much as movement is the name of this game called tennis, then Fabrice is the real deal. Agile, quick, effortless, small steps, excellent posture, a glider around the court. The problem he presents (as Gambill, Sampras and many others have encountered) is both his unpredictability, and the difficulty of getting anything by him. He truly weaves a spider’s web, ensnaring the opponent in a bewildering array of off speed shots coupled with just outstanding movement – the guy gets to everything.

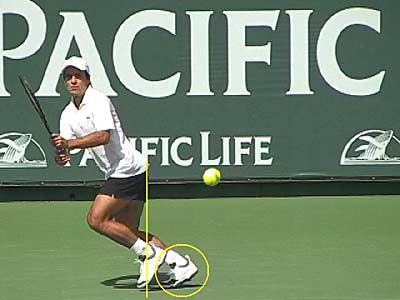

To borrow a quote from Pablo Casals, if the “most perfect technique is that which is not noticed at all,” then I believe one aspect that is overlooked in footwork is the time the ball takes to cross the net after the hit. Meaning, Santoro deftly adds speed when the opponent is in trouble, but reduces speed when he is out of position, such that he has perfected the knack for matching his ball speed and the time that ball takes to cross the net, with the amount of time he needs to recover. More than anyone else in the modern game, the Magician totally slows down the ball when needed to regain a centered recovery position, but you have to look closely to notice this. The Movement The third sequence shows the shot within the rally that forced Santoro to move the quickest and the furthest to get to the ball. Note as he reads the ball in the first photo his stance is quite wide, but his upper body is erect and alert without looking at all stiff. Within the Alexander Technique this is known as “monkey” and we have many excellent articles from Gary Adelman within our library on this type of postural style and movement quality. I have drawn a line to the middle of his foot with a reference on the backdrop on the “F” in Pacific Life. In the second photo Fabrice has moved this foot well beneath him as he has simultaneously turned his hips – a classic gravity turn. And finally in the third photo note how quickly he has transitioned to such a powerful running position. But it must be said, this has all been done not with explosive muscularity, but rather with a silky smooth effortless technique. So, apart from the enjoyment derived from watching this guy play, are there take-aways for you and me when on court? On the hitting side of the street experiment with “holding” your shot, using your feet and shoulders to hide rather than broadcast your intention. One drill is to have a friend feed balls to your forehand or backhand, and they simply lean either to their right or left just before you hit, to either indicate to you how you telegraph your shots, or the converse, how well you disguise your shots.

Another hitting version is to have your friend feed balls wide and to the corners, and see if you can float the ball back to the baseline such that you time your recovery split to the moment your partner strokes their reply. Yet another suggestion is to use a ball machine and see if you can play three shots from the same position without varying your stance – that is can you move to the forehand corner and stroke the ball heavily down the line, sharply and softly crosscourt, or lazily moonballing to either corner. The trick is to vary your stroke as it approaches the ball, rather than varying the stroke with different back swings. On the movement side of the street, I believe we can never really practice enough choreography at the baseline or at the net. That is, take a few minutes on court (or the back yard) and simulate an 8 stroke rally with movement to the forehand and then recovery, to the backhand and then recovery, to the backhand again but this time for a low and wide ball then recover, and finally another wide forehand with a winning (imaginary) down the line stroke. I believe (as I initially found) that rehearsing and practicing gracefully is much harder than you might imagine, but well worth all the time you might spend on this. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Jim McLennan's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

|

||||||||||||||||||