|

TennisOne Lessons

Federer and Coria – The Art of the Big Forehand

Jim McLennan

Last year, Guillermo Coria came within a whisker of the 2004 clay court crown -- holding a big lead before cramping and then not converting two championship points in the French Open final against Gaston Gaudio. He came oh so close to that prestigious title. Excellent movement, tremendous patience for the clay court grinding style, Coria definitely possesses a penetrating forehand.

Interestingly, some suggest this may be all that holds Lleyton Hewitt back on the French Open stage, for his forehand does not really “shoot through” the court but rather sits up waiting to be hit. Well, when discussing big forehands that shoot through the court, the other prime example is obviously Roger Federer. Both Coria and Federer can keep the forehand in play with heavy topspin, but equally both guys can create openings and hit through opponents when the opportunity arises. Unfortunately for both these guys, Rafael Nadal may just be the new guy on the scene, for he can match power with these guys, but equally his topspin forehand appears to have just a little more “jump” than we have seen which may move Nadal's opponents onto their heels ever so slightly.

So what strikes me in the following SiliconCoach presentation is how similar the forehands of Coria and Federer appear. And for those of you out there trying to learn the modern forehand, these two may be the best examples we can mimic.

Before looking at the particulars, let me offer a proviso. When developing and or executing any shot, the key to explore is the relation between effort and output. That is, how hard are you working, and how fast does the ball either spin or fly? To create significant topspin the racquet must move forcefully in a vertical direction as it meets the ball. To create significant ball speed the racquet must move forcefully in a horizontal direction as it meets the ball. To hit with power and spin the racquet must move both up and through the ball at impact. And to create such a forceful hit, a player must always monitor how hard they are working, whether their muscles are tensed or relaxed, whether the swing is rhythmic or staccato?

|

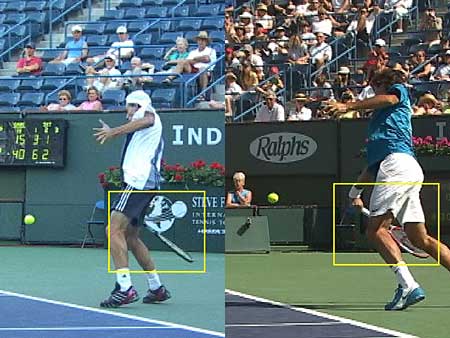

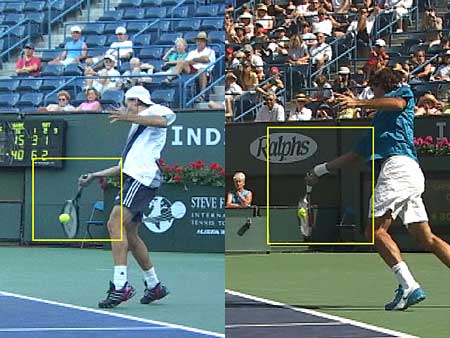

Click photo: Using the SiliconCoach video analysis software, Jim McLennan highlights two of the best practioners of the big forehand, Guillermo Coria and Roger Federer. |

What I believe you and I can try to model is the way these guys use their body much like children who play crack the whip when ice skating. The secret, though I have only visualized this game, is to be the first kid in the crack the whip sequence and not the last kid (the last kid is the one dangerously hurled into a snow bank or worse) and further, the secret, if you are the last kid is to refuse to play if there are six children in sequence as that chain will create much more whip like momentum than a chain of three children.

Well, to stretch that analogy (humor me here), it does appear to me that both these guys drive from the legs, which then turn the hips, which then pulls the torso, which then pulls the arm, which then pulls the hand and racquet. And in this kinetic chain the potential for whip like racquet acceleration is truly enormous.

A More Detailed Look

Again, video analysis is great for studying the dynamic flow of the entire stroke, but viewing each segment of the stroke in still photos gives us the opportunity to study the stroke a little more thoroughly. |

| Figure 1: Turn to the Side. Both players shift their weight to the back foot as they turn to the side. It appears they are more intent in drawing their hitting elbow back, leaving the racquet head up and forward. This is a classical pose within the modern forehand, but has little resemblance to how it was done when wooden racquets roamed the earth. |

Figure 1

Figure 1 |

| |

|

Figure 2: Crouching Before Acceleration. Both players begin to shift to the left foot, but you can see the crouching action more clearly with Coria. Both players begin to shift a little weight to the left foot, not really stepping in, but rather centering their weight for what will shortly become a “dual leg” drive. The racquet is picking up momentum as they allow the arm and racquet to “fall” at this moment of the stroke. |

Figure 2

Figure 2 |

| |

|

| Figure 3: The bottom of the Swing. Here, you can clearly see how low and closed they have swung the racquet head. |

Figure 3

Figure 3 |

| |

|

| Figure 4: Contact Well in Front. On these topspin drives, the racquet is positioned well below the hand. Now the fun begins. |

Figure 4

Figure 4 |

| |

|

Figure 5: Swinging up – Really Up. The racquet is still aligned in a position parallel to the net, as it was at impact, but this pronounced upward acceleration, captures the characteristic look and feel of the modern forehand. Some call this a “windshield wiper” action. The secret is positioning the racquet below the hand at impact and then rotating your arm quickly, very quickly. |

Figure 5

Figure 5 |

| |

|

Figure 6: The end. The weight has shifted to the left foot, the shoulders have turned as much as 180 degrees during this stroke. The ball has been whipped with a wicked topspin stroke. They are now balanced and ready for the opponent's reply, if there is one.

|

Figure 6

Figure 6 |

When comparing forehands one must note that these guys are not hitting identical shots. I don't know the court positioning of the opponent, how the ball they are returning was struck, or what Coria and Federer's intent was for these particular forehands.

That said the similarity is indeed striking. The only two discernible differences are the use of their head and eyes within the contact zone, and their grips. Federer, more than any other player on the circuit, stays totally focused on contact longer than anyone else.

In Figure 4 (and if you look back at the video at the top) we can see Guillermo pick up his head to read the opponent's reply a moment sooner than Roger is willing to do. And at contact, if you look closely, Coria's hand is positioned a little bit more under the handle, closer to a semi-western grip, while Federer appears close to a low eastern grip.

As you observe the overall sequence, note the ABSENCE of facial tension during the hit. Many players truly work to hit the ball, and you can see it in their faces. But in these examples we see excellent and effortless flowing rhythm. I encourage you to study, to see it in your minds eye when imagining the stroke and hit, then, imagine your own forehand looking and feeling just like this. Rhythmic. Flowing. No tension in the face, jaw or neck. It is doable, not easy mind you, but doable.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Jim McLennan's article by emailing us here at TennisOne. |

siliconCOACH Ltd produces a range of sports analysis software designed to analyze motion, enhance performance, and reduce the risk of injury. The video analysis software is now used around the world by athletes, coaches, sports scientists, teachers, podiatrists, physiotherapists, chiropractors, and biomechanists.

siliconCoach has many advantages over normal video. For example you can split a movie frame into two fields. This allows you to view 50 PAL/60 NTSC images per each second of original digital video which is essential to accurately analyze fast or complex movements. siliconCOACH Pro also comes as siliconCOACH Pro Server Edition for multiple users in an institution.

|

|

The Secrets of World Class Footwork - Featuring Stefan Edberg

by Jim McLennan

Learn the secret to the quickest start to the ball, and the secret to effortless movement about the court.

Includes footage of Stefan Edberg, one of the quickest and most graceful of all the professionals. |

|

|

Learn pattern movements to the volleys, groundstrokes, and split step reactions. Rehearse explosive starts, gliding movements, and build your aerobic endurance. If you are serious about improving your tennis, footwork is the key.

Includes video tape and training manual (pictured above). - $29.95 plus 2.50 shipping and handling |

|

|