|

TennisOne Lessons The Tipping Point in a Match by Jim McLennan "We never do anything well till we cease to think about the manner of doing it." William Hazlitt, English essayist

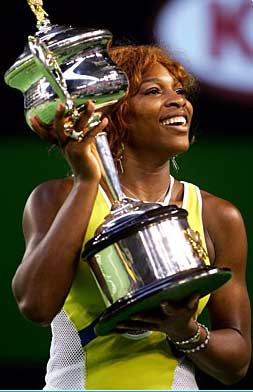

Radical momentum swings in a number of recent matches have caught my attention. At the Masters in Houston, semifinals, Roddick vs Hewitt, the match is relatively close, Roddick hitting big, Hewitt counterpunching, then somehow the rug is completely pulled from beneath Roddick. The big serving Texan loses the last 20 points in a row. During that stretch, Hewitt was not hitting winners, rather he was simply forcing errors. It is no small coincidence, in my opinion, that the Roddick, Gilbert split occurred a week or two after that match. Then in the semifinals of the Australian Open, Roddick cruises through the first set, loses two close tie breakers, and then falls off the cliff in the fourth set, winning only one game and a handful of points. Australian Open women's final the same thing. Williams and Davenport - match somewhat close, then Serena pours on the steam at the end of the second set, and in the final 6-0 third set drubbing, Davenport can manage only six points. I believe these same momentum swings and precipitous crashes occur in our matches as well, and it doesn't matter what level you play at. Somehow, a contest occurs when either player has an equal chance of winning. And as long as both players continue to believe in this contest, then the match can do down to the wire. The Safin, Federer Australian semifinal was just such a contest. 9-7 in the fifth indicates both players truly were in the match until the end. Federer may have lost a little sting on his forehand, highly unusual mind you, but nevertheless the level of competition was truly even. I am in no way suggesting that in the Hewitt Roddick encounter, or the Williams Davenport slugfest, the loser tanked. No way. Andy and Lindsay are both too proud and too professional ever to throw in the towel. But something remarkable truly did happen in these instances. In The Tipping Point, author Malcolm Gladwell discusses how little changes can often cause big, rippling effects, more or less on the principle of epidemics, where a small infectious agent can quickly spread among large numbers of people. And, just like the numbers of people infected with a bug, an idea, a thought, or a new style of dress can double and double yet again, something that was initially small and insignificant can grow to a size wholly unexpected.

I think that happens in tennis matches. Roddick is playing Hewitt more or less dead even. Roddick has strengths in his serve and forehand that can overcompensate for his less than stellar net skills, and to my eye, poorly hit backhand. He can miss a few volleys or a few backhands, but when everything else is in place, all is well. Additionally, the play of the opponent is also a factor. If Hewitt is off, then the volley and backhand are less of an issue than if Hewitt is totally engaged and playing well. Then there is a subtle error, but it occurs on a big point, and the error occurs within one of the suspect elements of Andy's or Lindsay's or your game. Just one error mind you, but the slightest “mental cringe” passes your interior landscape, just a flash and then it is gone and forgotten, or is it. The opponent senses the veritable “chink in the armor” and now Serena is emboldened. The next error, whether it is the same as the last one or from another shot entirely, and again the flash of doubt appears. And with the third or fourth flash, indeed there occurs a “tipping point” where flowing shots are now belabored, where pinpoint accuracy is replaced with cautious shot selection well inside the lines. And the culprit may be nothing more than analysis, and trying to think how to play, rather than accessing the unconscious state you were in earlier when doubt was not on the horizon. And more or less like the epidemic model, once the infectious agent spreads, there is little that can be done. Yes it may be that two or three “tips” occur in a match, but the critical tipping point is somehow the last one that always brings with it the precipitous fall from the cliff. Somehow the magic of tennis scoring can contribute in large measure to the tips. Ad in, ad out, long points, a close call, an over-rule of a winner. Consider that in the first three games of the critical fourth set in the Australian men's final, Safin has a number of break point opportunities in the first game but Hewitt barely holds. Then in the second game Safin has many hold opportunities but is broken, then Hewitt sensing an opening, holds easily for a 3-0 lead. Well, with the closeness of the first two games and perhaps their influence on Hewitt's hold in the third game, the score could just have easily been 3-0 Safin as it was 3-0 Hewitt. These swings in scoring test the players resolve, and test the player's present centeredness. Safin did not tip at this point, but there were many indications that either in previous years for Safin, or with lesser players in a similar predicament, a tip would have ensued.

So with the above in mind, and you now keenly aware of the tipping phenomenon as well as crucial junctures in a match where everything may either tip in your favor, or tip unalterably towards your opponent, what is one to do? Good question, and one that I will answer, though I confess I have been on both sides of this tipping point. First and foremost, play the game. That means, it is a game, and the trick is to play. Not for the sake of winning, but for the sake of playing. In that manner the shots and shot selection may become less conscious and deliberate, and more spontaneous and unconscious. Certainly everyone has played so well on occasion, but not really known why, nor been able to explain it. And when playing this well, no one really feels the need to analyze or explain. However, if your shots start to go awry, if the score is close and you miss on a forehand crosscourt by just that much, avoid the temptation to analyze, to scrutinize, and ultimately to doubt. Finally, become keenly aware of your opponent's disposition, their body language and changes in their tempo. For if in fact they are beginning to doubt, to overanalyze, and tighten up, then it is your turn, as we have seen Serena do so many times now, to step on the accelerator, play freely and assist them in tipping the whole darn thing in your favor. Remember there are two sides to this teeter totter – you and the opponent are working in concert here, at least tip-wise. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Jim McLennan's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

|

||||||||||