|

TennisOne Lessons Learning to “Give Up Control” Ego Tennis versus Aikido Tennis Doug King From the moment we pick up a racquet and hit our first ball, we strive to learn control. We learn grips, we develop concentration, we learn how to move our feet, and we learn stroking form. We learn how to prepare our racquet, how to properly set up our feet, and how to follow-through. We learn these things so that we can control the ball, and we are told that if we learn these things well enough, we will be able to make the ball do what we want. When we begin to compete in matches, we are told we need to develop a strategy. We need a plan to keep us on course. If we have a good enough plan and we stick to it, we will be able to control the outcome of the match. And on the emotional side of the game, we are told that if we develop confidence, then we will be able to hit the shots we want and emerge victorious. All of this is valid and I would not argue these points. Through discipline, hard work, practice, determination, and structure we can develop “consistency” and control over the ball and our opponents. But I would also suggest that this is only one side of the coin. Since some parts of the game are simply “out of our control,” at some point our efforts to control things can backfire on us. This is what we refer to as having “control issues”. Most of our training and focus is on trying to learn how to get better at the parts of the game we can control, but what about the parts of the game we cannot control? How much time do we spend focusing and training on getting better at managing those? How do we improve that side of the game? Do we even know what that side of the game is? Things “Out of Our Control” First let me explain what I mean by the parts of the game that are “out of our control.” Most obvious is the fact that one has an opponent and that opponent has a say in what happens. We can't decide what shot our opponent may hit or how well he/she will hit it. Although there are times when one can effectively limit what shots our opponent may hit, there are many instances when the opponent has options, especially on the serve. Even so, our opponent may not hit the shot exactly the way he intends on hitting it, and there may be random acts, like let cords and mis-hits that one must react to. Bottom line, tennis is a game of give and take, a game of send and receive, and getting good at the game requires not only be a good sender but a good receiver. To become a good receiver, you must be willing to relinquish a bit of control and let the other side have the floor. Not only can't you control the kind of shot your opponent is going to hit, in competition, you can't even control (choose) the opponent you are going to play against. This is left for others to decide. We call this, the “luck of the draw.” The fact is, one must be prepared to play anyone and everyone when they enter a tournament. Of course on the club level, many people control whom they play against and do so by limiting their “playing rolodex” to a select few. There is nothing wrong with that on a personal level, however, when you step out into the big, wide world of “open competition,” you can experience a harsh dose of reality. By limiting your playing partners you are selectively controlling your tennis experience. That can be reasonable, in as much as you want to avoid people that may cheat or stall or exhibit other forms of bad behavior. But, to eliminate people just because they don’t play the brand of tennis you like can be “over controlling,” and inhibit your overall development as a player. A more extreme form of this symptom can be seen with players who prefer to drill, rally, or even hit on the ball machine rather than play matches – probably because in a more structured setting of a drill, they minimize the “unknown.” In short, they feel more comfortable because they are more in “control.” Compare this with poker players, who at an early time, experience the cruel vagaries of fate and must learn how to accept the things that are “out of their control.” This does not mean that practice, skill, and good play are not important; it is instead, an understanding that there are certain aspects of the game that are totally random. If they cannot learn to deal with them in the proper way, they are going to be mentally and emotionally destroyed by the game. I’m not advocating playing high stakes poker, but like the gambler, a tennis players must learn how to properly deal with the things that are out of their control.

Why We Play the Game I love the statement (and I’m sorry that I don’t know who to credit it to), “we play the game because we don’t know who is going to win.” If we knew the outcome of a match beforehand, there would be no reason to play. There is nothing wrong with not knowing whether you are going to win or not. In fact, this is a critical part of proper mental preparation for a match. Yet we are told we will not win if we do not believe we are going to win. On the other side, we should never go into a match without an understanding that anything can happen. To believe that “thinking you are going to win” is a requirement for winning, is another form of an “over controlling” attitude. To believe there is any kind of predetermined mental equation that will guarantee a favorable result is simply wishful thinking and, perhaps, a false comfort for people who are afraid to accept the reality that anything can, and sometimes does, happen. We should simply go into a match with a positive attitude towards competing and accepting the challenges of the game; one of which is to be able to stay positive, focused, and relaxed under uncertain circumstances. After all, confidence is more about the elimination of fear and hesitancy than the belief in a victorious outcome. This is not easy because it is “uncertainty” and the “unknown” that often creates the most anxiety in people. Instead, we should learn how to enjoy the fact that in a tennis match, anything can happen. Instead of being an obstacle we need to fear and overcome, the “unknown” should be a primary motivation for playing the game. It should be seen as something positive rather than negative. We must learn to enjoy the uncertainty and the spontaneity of the game much in the same way a child eagerly receives birthday gift. The fact that we don’t know should only heighten the level of excitement and anticipation, rather than cause anxiety and fear.

Ego-Centric Tennis Tennis is a game of back and forth and give and take – a game of “act and react.” To be a complete player, one must not only develop an active side (stroking technique, getting set up, learning to form a game plan, etc.), one must also develop a “reactive” side (staying relaxed and open). One must learn the importance of being soft, light, empty, and impressionable. These are key characteristics of being “reactive.” Essentially one must be able to empty the mind of mental clutter and physical tension and flow with the ball – or, as the Chevy Chase character, Ty Webb, so articulately (if not pretentiously) put it in the classic cinema spoof, “Caddyshack,” “Be the ball, Danny. Be the ball” It is easy to say, “clear yourself of mental clutter and physical tension,” and another thing to do it. So, to imagine that we are going to eliminate these things entirely from the game is naive. But for most people, over-thinking and excessive tension are consistent problems. We need to learn how to “lighten up;” to rid ourselves of excess tension and skittish thinking; otherwise we become heavy and unresponsive. This state of being too forceful or too jittery is a state of acute “self consciousness.” When we are self-conscious, we experience a high degree of self-talk and self analysis – a strong urge of intent, of direction, and of control. In this state we have a very difficult time reacting to things with precision, both mentally and physically. Essentially, we are too preoccupied with our own internal dialog to observe an event with clarity. This sets up an inherent conflict that heightens our sense of threat. It becomes a vicious circle. The more we talk to ourselves in an attempt to gain control, the more distracted we become. We essentially become out of sync with the ball and our environment, and this adds to the level of anxiety. The result is, we either over-react in panic mode or we freeze up with indecision (another form of panic). Our bodies get lethargic and our minds begin to race uncontrollably. It is like a circuit that gets overloaded with impulses causing it to overheat rather than send messages in a clear and efficient manner. The irony is that often times, it is our attempts to establish and maintain control that lead to this state of being out of control. The results of this overly “egocentric” approach can range from being too rigid and “pushy” with our strokes, to being too stubborn with a losing game plan. Even watching the ball can be done in too forceful a manner since the body experiences a natural urge to tighten up in order to improve focus (the reasoning behind putting line judges in chairs and “locked” positions). Top players will talk about watching the ball with “soft eyes,” meaning they relax the facial muscles and “let” the eyes watch the ball rather than force (or over control) the process. This less forceful ball watching allows the player to shift his focus more fluidly so that he is able to expand his peripheral vision to the court and opponent when it is appropriate, and then narrow his focus just to the ball when that time is correct. This is key to “seeing the whole game.” In general, any time one is too deliberate (forceful) or if one deliberates too much (creates too much self talk), he becomes more self-conscious. When one is in a higher state of self-awareness (or self-consciousness) he is in a lower state of ball awareness (or externally conscious). The result is a dis-connect with the ball that leads to poor judgment and poor movement.

Aikido (Selfless) Tennis Instead of ego-centric or self-conscious tennis, I like to use the phrase “self-less tennis.” Self-less tennis is when we let our self (or ego) weaken. We do not give up awareness and simply tune out into a mindless state, but instead, we redirect our awareness away from self centered, deliberate thinking, to external focus on the ball/opponent/court. This will help us to react to the ball with more precision and efficiency. In reality, tennis is a “reactive sport,” and most of the time we are responding to the ball and our opponents. This reactive mode is a soft, fluid, impressionable state that is highly responsive, flexible, and unstructured. Even when the ball is hit to us, we must realize we cannot get into position right away but instead, we must proceed through a series of progressively finer adjusting movements, right up to the point of contact Great players are usually both adjusting to the ball and asserting themselves on the ball (driving the ball) at the same time. Lesser players make the mistake of trying to judge the ball very quickly and get “set up” as soon as possible. They commit quite early to the ball and the stroke, and are much more forceful (and much less reactive) as they approach the final moments leading to contact. The result is a “rush to judgment” before all of the “evidence has come in.” Often times coaches reinforce this response by encouraging players to prepare quickly; to get set up at the earliest stage and to plan their shots in advance. Better are coaches (like Oscar Wegner) talk of “stalking” the ball in somewhat of a smooth, stealth-like manner. They approach the ball like a little kid trying to catch a lizard, half expecting the ball to dart away randomly at the last moment. This way they never get so anchored in their feet or their swing path that they cannot fluidly make adjustments as they execute a stroke. I prefer to think of the proper rhythm much more like how a martial artist is trained to act. Aikido practitioners are trained to keep an open, relaxed, and aware mind, and to “let things come to them” rather than to try and meet oncoming objects forcefully. Key to successfully practicing this art is the ability to slow down the mind and also reinterpret the environment. All athletes talk of this same sensation of “time slowing down” while in the “zone.” In my opinion, what they are able to do is simply get their minds to relax so that they are experiencing and interpreting their environment in a non-threatened state, even though they are in a stressful situation. In essence, they are simply thinking in a normal manner. But since they are in a highly stressed situation and the natural response of the mind is to race wildly, they feel as though their mind is going in slow motion and that time has slowed down.

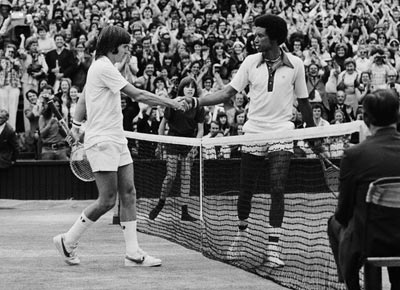

In learning this Aikido state of focus it is first helpful to understand the relationship between the mind and the body as it relates to a perceived threat in the environment. We all know that when the mind detects danger it will produce an emotional response of fear and a physical response of elevated adrenalin, heartbeat, respiration, etc… Being able to control how the mind perceives a situation is critical to managing the degree of “nervous tension” in the body. If we perceive a tennis game as a “battle,” we can sometimes burden ourselves with excessive stress that will not only make us less reactive and out of sync with the ball, but will also exhaust us, and potentially lead to injury. Convincing yourself you are “going to war” or that your opponent is “the enemy” may help to elevate your energy level which may help your physical output, but on the downside, it may cause judgment and timing problems. This is why professional players, when interviewed just before a match will usually say, “I’m just going out and try to enjoy myself.” They have learned how to “enjoy the battle,” to see it as fun, and they realize that if they are indeed on a tennis court, things can’t be all that bad. This is how an Aikido master learns to deal with an oncoming threat. He diffuses the situation mentally by eliminating the fear inducing associations attached to the oncoming object and to more clearly see the object for what it is. In a way, all of this response cycle starts in the mind, and in this regard, much of our performance eventually can come down to mental perceptions or attitudes. Some top players exhibit this kind of mental perspective. Pete Sampras and Roger Federer both have been noted (and in some circles criticized) for their seemingly distant emotional attitude on court. Others would interpret this as remarkable poise and mental toughness, akin to a martial artist. Perhaps the most famous example of an “Aikido” attitude was the 1975 Wimbledon Final between Arthur Ashe and Jimmy Connors. Connors, the world number 1, was the heavy favorite. But Ashe, employing a steady stream of off pace floaters and soft angled shots, took apart Connors while barely breaking a sweat. To keep his concentration, on changeovers, he would drape a towel over his head and sit monk-like in a seeming trance, later crediting his practice of meditation with legendary Dane, Torben Ulrich, as a key to his victory.

Helpful to adopting a less fearful view of the ball is to remind ourselves that we are rarely in any real physical danger on the tennis court. Now some would argue that it is dangerous and scary to be at the net, especially against a hard hitter. For those players who are afraid of being hit by the ball, that palpable fear at the net can be totally debilitating, and can often lead to miscues at the net that may be injurious. In reality, most of the danger we perceive in the game is self induced. Still the fear, whether real or imagined, has the same negative effect on our reactions – and truth be told, it is usually our egos that are most at risk rather than our bodies. In most cases, the worst thing that is going to happen to us in a tennis match is that we may lose a point or a match. Now that can be rather traumatic emotionally, but it is ironic that professional players, who have the most at stake to win and lose, usually have the best attitudes about accepting winning and losing, and take them in stride. They do not let the losses discourage them and sap their commitment, and neither do they let the wins inflate their egos to where they become over-confident and vulnerable. The true professionals do not let their ego, their pride, or their fears get attached to their view of things on court. They have learned that this attitude is key to producing optimum results. Balancing the Two Sides: Quick Feet and Slow Mind Like with everything else, the secret to exercising the right amount of control in one’s game comes down to balance and timing. When we play, we need structure and we need purpose. We need a game plan and we need to be mindful. When we play, we are never totally reactive and we are never totally self absorbed, although there are moments when we are close to these two extremes. For example, when my opponent hits the ball I am at the highest level of being reactive or “selfless.” At this moment, I am in “suspense.” I am in the middle of a split-step action which suspends motion from the body and at the same time I make a mental “clearing” action which suspends all thought from the mind.

On the other end of the spectrum, at the moment when I strike the ball, I am at my most "self aware." I am totally focused on what I am doing, which is driving the ball, or essentially telling the ball what to do. At this moment, I am no longer reacting to the ball but instead, the roles have been reversed. I am now intent on making the ball do my bidding. My only focus, at this point, is to be very clear and assertive in articulating my command to the ball. This is why players such as Federer and Nadal are so exaggerated on keeping their focus on the point of contact, even after the ball has been hit. This is a clear indication that their focus is not on the ball but instead on an internal directive they know from experience, will properly control the ball. We often refer to these two specific times of our play as “being in the moment,” and although we are told to always be “in the moment” when we play, in truth, we are in varying degrees of “being in the moment.” Most of the time we are “projecting,” that is anticipating. We anticipate where the ball is going to land when it comes off of our opponent's racquet and we anticipate where to hit the ball as we prepare to execute a stroke. When we are in the act of anticipating we are not totally in the moment, but there are times that we are completely in the moment, and these moments are at the times when the ball is being struck by either player. Still even while executing the actions that require projection or anticipation, it is ideal to do these in a manner that requires a minimum of conscious thought (or deliberation). This is because we must still be highly reactive to the ball. Also, the conscious thought that is relative to the game of tennis is actually quite narrow. So the fundamental challenge in tennis is to quiet the mind. I like to say that the great players learn to make the feet move more and the mind move less. Ideally, a player should develop relatively “reflexive patterns of response” that require minimal deliberate thought. Ultimately, the body feels like a flag that is "blowing in the wind," while the hands hold onto a flagpole to keep the body from flying away. Developing the Art of Non-Control

Another important way to encourage a more open attitude is to practice in a less structured and open way. First of all, play different styles of players. Don’t avoid the players you “hate” to play. I hear so many people complain about opponents, citing excuses like, “Oh, he isn’t any fun. He's just a pusher,” or, “He hasn’t got anything except a big serve,” or “She’s no good. She’s just really fast and she gets to everything.” These are all parts of the game and one can get dangerously deep in denial by not acknowledging that fact that these players may beat us. Besides, your game is not going to improve unless you expose it to players that can shine a light on your weaknesses. Secondly, play on as many different surfaces and in as many varied conditions as possible. Each surface suits a certain style of play, and by spending time on more surfaces, you will be able to expand your playing style. Also, mix up the places you play. Don’t avoid a court just because the sun isn’t right or you don’t like the background. Don’t cancel a match just because it is a little too windy to your liking. The more surfaces, surroundings, and conditions you can adjust t, the more tolerant and flexible you will become. The end result is that these conditions out of your control will have less of a negative impact on your game. Third, practice “ball feels” rather than “strokes mechanics.” Don’t over-structure your strokes. Try not to spend all of your practice time on specific drills. Learn to do “tricks” with the ball that require different spins and touches. Learn how to do gimmick shots with unconventional footwork, grips, and stroke patterns. This is not so you can dazzle your friends, but so that you develop more “ball awareness and feel” rather than “stroke consciousness.” Remember, the ultimate goal is to get the ball, the strings, and the target to come together, and if the body has to make a few contortions or compromises to make that happen, then by all means feel free to let it happen. Finally, learn how to willingly and happily accept the challenges of the game and embrace the elements of the game you cannot control. Every match is a new experience that holds certain surprises and revelations. Remember, just the fact that you are on a tennis court is reason to celebrate. So use that positive energy as your motivation to give your best effort and have the most fun as possible in the process. To quote Arthur Ashe, "Start where you are. Use what you have. Do what you can." There are no guarantees out there. The only thing that is certain is that you are not going to improve if you don’t keep playing, and you won’t keep playing unless you can find something positive in what you are getting out of the game. Conclusion While the ultimate goal in tennis is to control the ball, to get to that end we must take a very circuitous and sometimes paradoxical path. While we struggle to establish order through structure, repetition, and regimentation, it is not until we are able to compliment that structure with spontaneity, flexibility, and creativity that we can actually extend that sense of control to another level. There are simply too many things that we cannot control, no matter how much we practice, no matter how much we play, no matter how fast, how strong, or how technically proficient we become. To think that we, through the sheer force of will, can bend everything to our control is naive at best and dangerous at worse. We are not at the center of the game. Everything does not revolve around us, and the sooner we can learn to empty ourselves and become lighter and more responsive, the more in tune we will be with the ball. Just as one must balance offense with defense, topspin with underspin, and strength with flexibility, so too must one compliment control and spontaneity. The goal is not to "lose control," but rather to "give up control." Like everything else, learning this skill requires judgment, practice, and time. Remember, we “play” tennis, and the more you can see it as a game of exciting challenges rather than a life and death struggle, the more you will be able to lighten up and possibly take your game to that next level. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug King's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug is one of the country's foremost tennis teaching innovators. Founder of Acceleration Tennis, a revolutionary teaching system, King is leading the way in reinterpreting the traditional tennis model. Doug King is currently Director of Tennis at Meadowood Napa Valley ( www.meadowood.com ), a Relaix Chateau Resort in St. Helena , CA . For more information on Acceleration Tennis please email Doug King at dking@meadowood.com. |

Doug King studied with legendary tennis coach Tom Stow and was a

former California State Men's Singles Champion

and the former number one men's player of Northern California.

Doug King studied with legendary tennis coach Tom Stow and was a

former California State Men's Singles Champion

and the former number one men's player of Northern California.