|

TennisOne Lessons Developing a "Feel for the Game" or “Stinkin’ Thinkin’” and the Boyd Cycle Doug King As players and coaches we spend a great deal of time and energy detailing the various body and racquet movements involved in the tennis stroke. We breakdown the turn of the shoulders, the grip change, the footwork, the backswing and the follow-through to somehow uncover some hidden secret that will unlock the mysteries of a perfect stroke. But one of the most critical human components in the stroking process may also be the one that receives the least amount of attention; that is the mind. The mind is the command center where sensory input is processed and converted into appropriate neuro-muscular response. It is where all action and emotion emanates from and yet we devote relatively little attention and discussion to this process. That may seem to make little sense but there may be logical reasons why this is the case. One reason we tend to ignore the role of the mind is because the mind is so complicated it almost defies analysis. We have a hard enough time trying to describe the proper movements of the racquet in a stroke, but the racquet can only go as far astray as the arm can reach. Try applying that same kind of analysis to the mind, which is unlimited in its speed and scope of travel. The mind can go almost anywhere in time and space and in only a matter of micro seconds. It is often skittish, capricious, and unreliable. Once you start breaking down thought patterns you open a can of worms that can often lead into a labyrinth of confusion and doubt – and that can easily lead you further astray rather than closer to the answer. Another reason discussion or analysis of the mind is so often counter productive and thus avoided is that the object of the game of tennis is to control the ball, and a huge part of controlling the ball is focusing on the ball. Since the ball in tennis is moving around so much, the fundamental mental focus should be on that moving ball, and the more things that the mind has to focus on the harder it is to stay focused on the ball. Thinking about what the mind is doing is only making it more difficult to focus on the ball itself. Therefore most talk or analysis about the mind is simply discarded as being distractive. “You’re thinking too much” is the common criticism and thinking about how your mind is thinking (“thinking about thinking”) while trying to hit a tennis ball is definitely thinking too much. On the other hand, tennis involves more than simply keeping your eye on the ball. You must also be able to execute a strategy – and that strategy is developed in the mind. This formulation of a strategy or plan of action involves deciding how and where to hit the ball and also where to move on the court. It is a very complex and sophisticated process. To do this you must be able to assess your situation, project into the future to anticipate developing conditions, and you must be able to refer to the past in order to effectively predict the future. You must be able to not only watch the ball but also “see” many more subtle situations and relationships involving you, your opponent, and your environment in order to effectively implement a strategy of shot selection and court positioning. Therefore the mind must be able to move around within an arena of awareness and be able to handle a variety of functions in a systematic process. This is why it is quite a different experience when you simply either go to the court and hit on a ball machine or rally crosscourt than when you actually play a match. When you are on a ball machine or when you are rallying your mind is managing a number of variables which defines a certain scope of focus. On a ball machine you typically know what kind of shot is coming at you and you have a certain script to follow. The scope or range of focus is relatively small. The same is the case when you rally. However when you actually play a match that scope is opened up immensely. You have many more variables since you are playing against an opponent who is plotting against you and therefore unpredictable. And another significant factor is that you now have consequences – that is winning and losing. All of these things complicate the “mental” landscape and it is very easy to get overwhelmed or out of sync. It is similar to learning how to juggle. You may be able to juggle two balls fine and indeed you are “juggling.” But if you add one or two more balls everything goes kaput. Now you aren’t juggle anything at all. The challenge in tennis is not so much in acknowledging the role and the significance of the mind and the complexities of the decision making process but more so in developing an approach to the “mental” side of the game that is not counterproductive – that is; does not create “thinking about thinking.” The problem with much of our learning is that through the articulation and focus on the process we become distracted from the actual object of that process. It becomes a mental “Catch 22” which has prompted the old adage that the best way to disrupt your opponent’s concentration is to ask him what he is thinking about while he is hitting a ball. My way around this paradoxical quagmire is to try to develop a parallel model between how the body moves and how the mind moves. The goal of the movement of the body is to develop form, balance, rhythm, and timing. In a similar sense the goal of the mental side should be to develop form, balance, rhythm, and timing. The thoughts must have “form,” that is a scope or arena or range, much like how a corral creates a “form” by defining a certain space. There are certain areas that your simply mind should not go to, such as “what will happen if I lose this point,” or “I should have dumped those shares of CRP at 7.” These thoughts are “out of bounds” or not in form. Also the mind must learn to develop a particular pattern to its thought process; taking observations, thoughts, and decisions in a specific sequence. In this respect there is rhythm to the mental process. And the mind must keep these observations, thoughts, and decisions in sync with the ball and the opponent. In this sense there is “timing” to the mental process. So in a sense the same traits and skills that we try to develop in our physical bodies and physical movements are the same traits and skills that define the mental game. In fact the parallels go well beyond that. By seeing the mental process as an “organic body” it can help to develop a way of approaching the mental side of the game that is less confusing and more manageable.

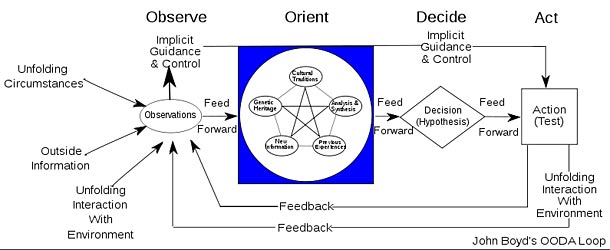

The Boyd Cycle: OODA (Observe-Orient-Decide-Act) As daunting as it is, grappling with the mental side of performance is nothing new. A very interesting and now widely accepted articulation of the decision making process was developed by John Boyd, an unconventional fighter pilot who in the 50’s earned the nickname “40 Second” Boyd for his reputation for being able to win any dogfight in 40 seconds or less. His uncanny success spurred a military study and subsequent training methodology in the 70’s based upon Boyd’s decision making technique which became known as the OODA Loop or the “Boyd Cycle.” Boyd postulated that any conflict could be viewed as a duel wherein each adversary observes (O) his opponent's actions, orients (O) himself to the unfolding situation, decides (D) on the most appropriate response or counter-move, then acts (A). The competitor who moves through this OODA-loop cycle the fastest gains an inestimable advantage by disrupting his enemy's ability to respond effectively. He showed in excruciating detail how these cycles create continuous and unpredictable change, and argued that our tactics, strategy, and supporting weapons' technologies should be based on the idea of shaping and adapting to this change - and doing so faster than one's adversary. “The Boyd Cycle is a decision making model, which focuses on how we process information, through all of our six senses (sight, sound, smell, taste and touch and also intuition). A “turned on and tuned in” Boyd Cycle running smooth and fluid allows us to recognize patterns of behavior in conflict, orient quickly and effectively to the climate (situation) we are in, allowing us the ability to make rapid decisions and take appropriate actions to exploit any advantage that presents itself.” (Karl Bridges).

Note the emphasis on “smooth and fluid” for this is a key to maximum efficiency, for both movement of the body and mind. Even though speed of execution is one of the highly beneficial results of a properly operating OODA Loop the key is efficiency of movement. The Boyd Cycle is a very specific formula and the successful execution of that ordered cycle in a sequential, timely manner is the goal.“ An effective OODA Loop always favored agility and precision over raw power in dealing with opponents in any human endeavor.” Applying the OODA to Tennis The Boyd Cycle has been shown to apply not only to battle situations but has also been proven to be a very effective in all arenas of competition whether in sports, business, or other arenas of human interaction. The parallels to the sport of tennis are quite direct. The first stage of the OODA Loop is “observe,” and this is true in tennis. Although obvious, it is not as easy as it sounds. To properly observe requires a high degree of emotional detachment and keen focus. The mind must be clear of extraneous thought and distraction and intensely postured in the present. One major challenge when we first observe the ball coming off of our opponent’s racquet is being able to free our minds of our expectations and our intentions. These thoughts will clutter the mind and dislodge us from the present and interfere with our ability to precisely and accurately observe what is going on. The goal is to achieve a state of focused, engaged neutrality. The second stage of the cycle is to “orient.” In this stage we must be able to properly synthesize and analyze our observations, that is, we must create a reality out of what we observe. If, for example, we see dark clouds forming we would anticipate rain and this would then allow us to respond with appropriate action. Simply noticing that dark clouds are forming would not be particularly valuable if we could not recognize the relevance of that information. This process of orientation is perhaps the most complex as it involves not only recognition of external phenomena (the ball and the opponent) but also the integration of those constantly changing variables into pre-existing, more stable conditions (your and your opponent’s strengths and weaknesses, geometric and physical conditions of court, sun, wind, etc…) We also have the physical implications of orientation and that is getting our bodies properly oriented to the ball. These “orienting” moves could be considered “actions” although they are almost involuntary trained responses – again underlining the blurred nature between the physical and the mental sides of the game. The third stage is to decide. As we finalize our orientation to the ball we must make a decision on how and where to hit the ball and where to subsequently move after the hit. This decision is formulated based upon the synthesis of the data inputted and our ability to orient to the situation. We must be able to take our observations and recognize our orientation and then decide which of our options presents the best course of action. The final stage of the process is to act. This, of course, is the physical execution of our decision making and involves not only the stroking of the ball but also our physical positioning on the court. When your mental process is functioning smoothly not only does this create more clarity and confidence and ease in your play but it also results in more insecurity, doubt, and panic in your opponent. This is one of the important results as expressed in the Boyd Cycle. The OODA Loop is not just about one side of the competitive environment, it’s about both sides and you getting inside the mind of the competition as Boyd described; “Operate inside the adversaries observation-orientation-decision and action loops to enmesh adversary in a world of uncertainty, doubt, mistrust, confusion, disorder, fear, panic, chaos… and or fold the adversary back inside himself so that he cannot cope with events/efforts as they unfold.” When two sides of a competitive situation are in conflict, the side that can execute the Boyd Cycle (OODA Loop) process more rapidly and more effectively than the other will gain the advantage over the opponent because initiative is seized and the opponent will constantly be reacting to the decisions of the opposing side. This leads to poor decisions on the part of the opponent followed by paralysis of the opposition’s decision making process. This is what Boyd meant by “operating inside the enemies decision making cycle.” (Fred Leland; Lieutenant with the Walpole PD and police and security personnel trainer) If you observe, orient, decide, and act efficiently you will create more options for yourself and better disguise your own intentions. This will force your opponent to guess more, increase his anxiety level, and deteriorate his general mental state. To reduce the entire decision making process to a simplistic formula can seem very naïve as there is a tremendous amount of complexity to each stage of the cycle. In addition there is a great deal of overlap between the stages that makes it rather ambiguous as to where one stage ends and another begins. For example, as the player begins to orient himself to the ball he is still receiving information and observing developing conditions whether that be the ball, the opponent, or other aspects of the environment. As soon as the ball comes off of the opponent’s racquet there is a preliminary OODA loop (what we might call the “initial turn”) followed by the accumulation of more information and then a series of reactions timed to the unfolding of decisions and actions. In reality it is a flow and blend of these stages that tends to run together in a smooth and fluid process, still the decision making process does follow a systematic formula as described by the Boyd Cycle. Common Miscues: Prejudging, Biases, and Jumping to Conclusions When the decision making process is running smoothly and efficiently the result is that the overall game is executed with more speed, precision, and accuracy and less effort, confusion, and panic. Although speed of execution is a desired result it can also be the source of a common breakdown in the process. Often players are much too eager to make a decision about what kind of a shot to hit or where to move rather than waiting until they have properly accumulated information. In a way they “short circuit the loop.” This is what I call “jumping to a conclusion.” You can see this when players “over react” and they start quickly but then end up getting prematurely frozen. Or they may not react at all because they are simply frozen trying to make too many decisions too quickly. They get frazzled by decision-making overload and end up like the proverbial “whirling dervish” where a lot is going on but nothing is happening.

Making decisions requires a certain amount of patience to let the information “come to you.” This is especially true in doubles when things can change so quickly. In such a case a simple step in one direction by one player can change the complexion of a situation quite dramatically. In these instances it is important to keep options open and not commit to a final decision too quickly. This over-anxiety to commit to a determination can also send overt signals to your opponent that allows him to anticipate your shot intention. Remember that the "D" in the OODA Loop the “deciding” comes next to last so don’t get “jumpy.” Another common mistake is “prejudging.” Pre-judging is when you have over anticipated and you have made a determination of an event before it has actually happened. This occurs when we prepare ourselves for a probable return from our opponent but we fail to get into a proper “neutral” position when our opponent is making the shot. Instead we remain focused on what we have anticipated and therefore have not achieved a proper state of awareness; that is we are focused more on what may possibly happen in the future as opposed to what is actually happening in the present. Being “biased” is another form of prejudging except that it involves preconception or inclination attached to past events or one's personal history. It may be that your own backhand is weak and therefore you project that onto other players. Or perhaps if your backhand is weak you are constantly worrying about what to do if the ball comes to that side. You may over compensate in terms of your court position, your shot selection, and your mental focus. Keys to Developing a Decision Making Routine Part of developing an effective decision making pattern starts by keeping things simple. Although it is a very complex process and easily overwhelming when it is considered in its entirety, there are some keys to improving your mental skills. Below is a general guide to improving your mental skills. Although each category is a deep well of subject and practice, seen together they form a useful perspective. 1. Start From the Beginning: Learn how to relax and quiet your mind during the “in between” times (in between games, points, and even shots). Good observation starts with a quiet and focused mind so practice calming and focusing and bringing your mind under control.

2. Keep it Simple: When the ball is hit to you don’t try to do too much at once. The first decision you need to make is as simple as “forehand or backhand” and there is an appropriate physical action that corresponds to that decision. Let the rest of the decision making of where to hit the ball and where to move come to you a bit later and in a more relaxed rhythm. Let the play come to you. 3. Stay Within your Comfort Zone: Don’t try to play shots that you aren’t confident with. If a down the line shot is open it doesn’t mean that you should necessarily go for it. Be sure that it is a shot you feel relatively secure with. The mental stress of a low percentage play will create doubt and anxiety that will distract you and undermine your success. Avoid panic at all costs. No matter how dire the situation keep a clear head and make the best decision possible. 4. Keep an Open Mind and a Flexible Attitude: Developing a mental routine does not mean becoming stubborn or pigheaded. Keep a focus but don’t “bear down” mentally to the point where you are exhausting yourself or becoming “narrow minded.” Never underestimate your opponent nor take situations for granted. 5. Stay Within Form and Rhythm: Try to see your focus and decision making process flow like a jelly fish bobbing up and down in the water; it moves smoothly, opening and closing, and shifting. It starts quite soft and open and then shifts to a very narrow and tight focus on the ball at the point of contact. There is rhythm to how the focus shifts and there is timing of that rhythm with the ball. 6. Build Up Your Mental Endurance: Don’t let your mind stray “out of bounds” or lose focus. When we get tired our minds start to wander. When we are under stress our minds will drift towards negativity and panic. The mind must be exercised and disciplined constantly to develop the skills of strength and agility necessary to execute. Develop your physical conditioning to improve your mental focus – they go hand in hand. Conclusion In the game of tennis the concept of “thinking” has become a pejorative. How often do we hear players castigate themselves for “thinking” too much? On the other hand we often laud a player’s ability to come up with the right shot at the right time or to employ an effective strategy and we refer to those players as “smart players.” Clearly there is a right and a wrong way to think on the court. The problem is that delving into this subject is just so confusing and complex that it can easily create more harm than good. It’s true that for most people the tendency is to “think too much” but I would suggest that it is not necessarily thinking too much that is the problem but that it is simply thinking “improperly.” We tend to get out of sync or disorganized with our thinking, we panic and freeze up or over react, or we simply can‘t get the mind to settle down in the right place, and when this happens we automatically assume we are thinking too much. To get a better perspective try to compare it to how your physical body must perform on the court. A good player seeks balance, form, rhythm, and timing to the physical movements of the body. One would try to develop all aspects of movement whether it is moving the body faster or increasing the range of movement of the body, but you would never try to intentionally “decrease” your body’s ability to move. You would seek to increase that range and speed of movement and then learn how to integrate those skills to the specific rhythms and situations of the game. In the same way the mind must develop a similar ability to stay in form, balance, and rhythm and also stay in time with the movements of the game. But one should never consider that general “thinking” is bad. By seeing these two aspects, the physical body and the mental body, as having a similar structure and profile you will find it easier to get a feel of these parts working in sync with each other. To say that developing efficient decision making skills is important is not to say that it is everything. In tennis the ability to out hit, outrun, and outlast your opponent can often trump observing and orienting skills, and a good attitude can not always compensate for a bad grip. Still the ability to maximize your physical skills is intrinsically linked to your ability to think clearly and keep your wits about you. When you are able to get both the physical and the mental sides working well together, not only are you moving well and seeing the ball well, but you are really “feeling the game.” Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug King's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug is one of the country's foremost tennis teaching innovators. Founder of Acceleration Tennis, a revolutionary teaching system, King is leading the way in reinterpreting the traditional tennis model. Doug King is currently Director of Tennis at Meadowood Napa Valley ( www.meadowood.com ), a Relaix Chateau Resort in St. Helena , CA . For more information on Acceleration Tennis please email Doug King at dking@meadowood.com. |

Doug King studied with legendary tennis coach Tom Stow and was a

former California State Men's Singles Champion

and the former number one men's player of Northern California.

Doug King studied with legendary tennis coach Tom Stow and was a

former California State Men's Singles Champion

and the former number one men's player of Northern California.