|

TennisOne Lessons Is "Stepping In" Holding You Back? Doug King Besides "keep your eye on the ball," one of the most time honored adages of teaching tennis is "step into the ball." What this has historically referred to is striding forward towards the net and playing the ball off the front foot. Stepping into the ball has always been associated with good preparation, good footwork, and confident, aggressive stroking. And even though the notion of "stepping into the ball" has been challenged in recent years through the popularizing of "open stance" strokes (most notably the forehand but also more frequently on the two-handed backhand while the one-handed backhand remains a fundamentally closed/neutral stance stroke). we still hear announcers commenting consistently on the merits of stepping into the ball, taking the ball early and stepping up in the court. So exactly what is the proper way to align the feet when stroking? Well like with most stroke issues the answer isn't as black and white as we might like. While under most conditions I advocate stepping into the ball there are many exceptions and common misconceptions when it comes to aligning the feet and shifting the weight in a stroke.

What I would like to address in this article are two things. One is to discuss the common misconceptions of weight shift and to illustrate some techniques for correcting weight shift problems. Secondly I will argue that our adherence to over simplified "tips" can lead to developmental problems. what these common misconceptions are and In earlier articles I have suggested that leverage and torque are the primary sources of power in the modern game and this has caused us to reevaluate how we consider footwork. Our footwork patterns should be based on our effort to establish proper leverage against the ball at contact and this is very different than simply stepping into the ball. The Body as an Obstacle In my experience the most difficult thing for players to learn is rhythmic movement. Movement must flow though the body like the way water moves when it is stirred around in a bowl; smooth and continuous. Instead, we often see movement that is herky-jerky, stiff, and labored. This is usually because there is too much emphasis put on specific parts of the movement rather than trying to develop the stroke movement as a whole. This mistake usually follows this scenario; the player starts by making sure he gets ready quickly. He turns quickly and takes the racquet back quickly. Then he tries to step into the ball and makes sure he follows through. If a player concentrates on these key elements and is able to execute these specific actions, he will have produced a good stroke. I think this is a great prescription for failure. By putting so much emphasis on specific aspects of the stroke you tend to end up with exaggerated movements that are jarring and disjointed. Secondly, you put undue weight on the consequences of specific actions that create huge flaws in reasoning. For example, when we prepare the racquet quickly we feel that we have prepared well. This is simply not true. You can prepare "too early." When we prepare too early we have too much time on our hands which leads to too much thinking. (How many times have we complained about thinking too much?) We also tend to get stiff because when the arm/racquet comes to a stop it tends to freeze up. Getting stiff, anxious, and losing concentration are some of the problems that occur when we prepare too early. Yet we are conditioned to think that early preparation is good preparation and that the only problem that preparation is designed to address is to "not be late." In my opinion this flawed logic is the result of putting far too much emphasis on getting prepared early and the result is a very skewed view of stroking rhythm and the role of stroke preparation. I specifically mention this problem of racquet preparation because this is inherently linked to the problems that arise with stepping into the ball. When the turn and the take back of the racquet are done too quickly, it results in a pause in the backswing. When the racquet stops in the back, it loses momentum and flow, then momentum has to be reinitiated in the swing. In essence, the swing has to start all over again. When this loss of momentum in the racquet occurs in the backswing it forces the body to overcompensate by having to restart the entire swing midway through the stroke, forcing the body to shift forward too much and too soon. This symptom is called double clutching and it often results in late hitting. Because the body is forced into an exaggerated forward weight shift it actually throws off the timing of the swing and the spatial relationship between the hands and the body (see my article "The Leverage Game: Get Behind It" and "The One Handed Backhand; How We Lost Our Way"). This is especially the case when the student is under the impression that stepping into the ball is an important key to power. You can see how one exaggerated movement (in this case "getting prepared early") can result in mechanical flaws that lead to another overcompensation (in this case automatic "stepping into the ball") The truth is, stepping into the ball has relatively little to do with power (a myth which I will explain later) and people who are under the impression that stepping in does play a significant role in the generation of power usually tend to get their bodies in the way of their strokes rather than get their bodies into their strokes. When the body moves forward too soon and leans into the ball, the frequent result is that the hands cannot "get through" the contact and the ball is played "late" (too far behind the body). When this happens the stroke will invariably break down (the racquet twists in the hand and/or breaks away from the target prematurely) and there will be no "follow-through." This is a common mistake (seen especially on forehands) and is part of a vicious cycle of flawed stroking. It begins with the idea that you need to get ready quickly and it gets worse when you rely on stepping in for power. It comes at the cost of great effort and usually ends with poor results.

Proper power is the result of a very well coordinated series of interconnected movements and one aspect of the sequence cannot be more heavily weighted than any other. "Stepping in" is one of a series of overused catch phrases that people bleat out simply by default. "Get ready," "follow through," and even "watch the ball" are so carelessly tossed about by both coaches and players that people end up thinking that the entire game is built upon a fervid commitment to execute these commands. This over-emphasis on stroke "segments" leads to mechanical play and jerky motions. Instead, the parts need to be kept in proper relationship to the rhythm and flow of the entire stroke and each piece must carefully and "organically" lead into the next move with the intent of creating a singular seamless action. The Power Myth "Stepping into the ball" has always been considered a key element to power in stroking. Stepping into the ball for power is actually a bit of a myth. Stepping out with the opposite foot and shifting onto that foot while hitting is not the most powerful way to transfer weight. This kind of weight shift is relatively slow and in fact it is akin to "walking into the ball." I don't think that anybody would encourage the idea of walking into the ball and certainly they would not associate that action with a powerful stroking movement. Stroke speed is a fundamental factor in power and walking into the ball is not going to produce speed. Stroke speed in tennis is produced by spinning action much like how an ice skater spins. Turning into the ball is faster than "stepping into the ball" and turning into the ball can be done off of either foot. A similar example is baseball hitting. When a batter hits a particularly powerful ball he is said to have "turned on the ball." No one says he has stepped into the ball. In fact some of the most powerful baseball hitters in the game barely even step onto the front foot but instead keep their weight on the back foot and rotate on the ball of the back foot. Jim Thome, one of the most prolific power hitters in the game, is a great example of this. When he hits the ball he consistently keeps the toes of his front fool off the ground throughout the swing. Thome keeps most his weight back on his back foot and he spins hard on the ball of the back foot and the heel of the front foot., If the body shifts too far forward onto the front foot the body actually gets in the way of the hands and slows down the swing action. Also the body moves in front of the hands where there is less leverage from the body in getting the hands to create bat speed.

Besides rotational motion the other critical part of developing speed is through the use of the smaller muscle groups, namely the forearms, wrists, and hands. Speed comes from these parts because they have a much shorter turning radius. Speed is produced by a series of well orchestrated coils and uncoils of the body, starting with a buildup of energy from the large muscle groups and then funneling that energy into the rotations of the small muscle groups. Significant stroke speed ultimately comes down to good arm action and good hands. We often call this a "live arm." What is critical to understand is the difference between stance and weight shift. A stance does not determine the type or the timing of the weight shift. People often erroneously assume that if someone is using a closed or neutral stance they are hitting off the front foot and if they are using an open stance they are hitting off the back foot. Just because someone uses a certain stance does not mean that they do or don’t hit off of the front foot or that they even shift the weight forward. Instead there is a stroking axis that the body rotates around and this axis can be centered on either foot or somewhere in the middle. A forward weight shift is accomplished by making a well balanced and rhythmic rotation on this axis (called “squaring up” the body) and it can be done from any kind of stance and by stepping forward, standing in one spot, or even stepping backwards. The timing of this rotation is critical and moving the weight forward at the wrong time, whether late or early, will compromise power. A top player can wind and unwind off either foot or any variation of footwork pattern. They understand that effective power is produced by the controlled timing of these body rotations with the ball and speed and power are more associated with the fine motor actions of the arm and hands. Developing a "Live Arm"

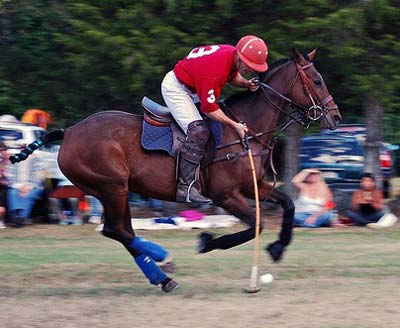

If you look at any sport that is dynamic, like baseball or football, you can see that infielders and quarterbacks must learn how to throw out of a variety of positions. A quarterback must learn to throw across his body or even when backpedaling. He learns how to make a quick release so that linemen cannot block his pass. And a second baseman must be able to fire the ball to turn a double play with great speed and accuracy even from any number of awkward positions. In polo a rider must learn how to get his mallet on the ball regardless of the movements of the horse. Riders call it an "independent saddle" and they can smack a powerful shot even when the horse is moving in an opposing direction. In all of these sports the key is to create good arm action. This is really the key to speed. The arm creates speed through a series of bends and rotations, lags and accelerations, and key to them is the roll of the wrist and forearm. This is where the final and quickest action is going to take place so instead of thinking of stepping in for power what we should be concentrating on is using good hands for power. A perfect example of this is the serve. On the serve we concentrate on "snapping or rolling the wrist" (I don't want to debate this here) and this is because it is the best way to produce speed. The body will add into that but the body is secondary to getting the hand correct. If the hand isn't right, it doesn't matter what the body does, there will be little speed produced. And here is the big catch – when we think that the body has a greater contribution to power than it really does we start relying too much on the body and we never get a good arm action. This is a frequent problem because, let's face it, most of us have a problem of staying relaxed and developing our fine motor actions. Most of us are much more forceful and anxious and so we are naturally inclined to overpower things and overdo things. So we have a natural inclination to want to "muscle" the ball and use the body too much. Stressing "stepping into the ball" only reinforces this tendency to muscle the ball by overemphasizing the body action and thus we never develop good hands and a live arm.

Going back to the serve as an example of how we want to develop power by fine tuning the small muscle groups of the arm, we are often taught to do this by taking the body out of the stroke. By removing the body from the shot this forces the arm to educate itself into the proper sequence of rolls, bends, and lifts to achieve speed and power at contact. This is done by a few different techniques. One is to have the player serve with his feet planted together throughout the serve (actually Roddick almost does this). Another is to have the player serve from a kneeling position on the court. Both techniques will take the body out of the serve and help the player to develop a live arm which is the real key to speed and power. The same can be true on the groundstrokes. Even though there is less wrist action on the groundstrokes, there is still a heavy reliance on the arm and hand action to produce speed. This was the basis of the training chair that Thomas Muster, the "King of Clay" and former world number 1, used to rehab after severe knee surgery in '89. Strapped to a chair Muster hit countless balls to maintain the lethal power level on his groundstrokes by keeping good arm strength and technique. If the situation were reversed and he had his arm in a cast rather than his leg, no manner of stepping into the ball or footwork pattern could come close to replicating that same level of power. Stepping In and Timing The concept of stepping into the ball has more relevance to timing than it does to speed and power. If the ball coming to me is low and dropping or slow and I didn't want to hesitate in my swing, then I would step into the ball. In deliberate practice (either being fed balls or hitting on a ball machine) we are often hitting balls like this. If we take a lesson the pro usually hits us nicely paced balls that are dropping just a bit in front of us so that we can naturally and comfortably step into the ball. Typically the pro congratulates you on what a good shot you hit and explains that it was a good shot because you stepped into the ball. Actually the entire scenario is orchestrated so that the only logical footwork under those circumstances is to step into the ball.

Similarly when we set up the ball machine we usually set it up so that the ball is coming the same way – again reinforcing the misconception that stepping into the ball is the essential component to hitting good shots. Through overly controlled practice conditions we can learn to "groove strokes" but we can also get ourselves into a rut. When we repeat these controlled shots over and over we tend to not only get too patterned in our movements but we can also easily make erroneous associations and conclusions about what the good stroking fundamentals are based on. Then, when you get into live play and you try to step into every shot, you'll most likely make errors and you won't be able to explain or figure out why. The fact is a good shot isn't the result of stepping in but a good shot may include stepping in. It may also include stepping back or stepping to the left or stepping to the right or even jumping up in the air. Not every "good shot" is going to be hit the same way, but every good shot will effectively conform to the specific conditions of that particular instance. Look at the series of videos below to see how players adjust their feet to the timing of the shot. You can see that regardless of the type of shot (forehand, single-handed backhand, or double-handed backhand), it is clear that these strokes are played out of variety of stances. Despite the type of stroke and the footwork pattern that is required there are two things are always evident; one is that the body seeks to find the optimum position for leverage to the contact point, whether that is moving forward, back or to the side. And secondly, regardless of what the body may be doing the arm and hand are making a rhythmic action to the ball, that is there is good hands and a live arm action which results in good speed and power, even when the body cannot step in. Footwork and Flexibility: Why to Practice “Wrong Footwork” A common mistake is to think that if we can groove a perfect stroke then we can master any situation. After all when we watch the pros they look like they hit every ball exactly the same every time. In a certain way they are hitting each shot the same and in another way they are hitting the ball differently every time. They are making good contact every time, they have good tempo and rhythm every time, and they have good form every time, but they also change things constantly. They change the size of the backswing, the timing, the spin, and especially the footwork. The racquet is the thing that hits the ball and there is much less tolerance for variance there. The things that are designed to accommodate great change are the feet and so they have to be the most flexible, adaptable, and creative in order to realize their role.

And make no mistake the game of tennis is full of surprises and constantly changing conditions. To think that you can manage this landscape with a scripted program is naïve. It is fine to work on consistent stances and footwork patterns, but at some point it is equally important to abandon patterning and to let the feet go. Or expand your patterning to include a wide variety of stances and stroking footwork. In this way you will be comfortable with playing the ball in a variety of situations. The important thing is to eventually develop strength, rhythm, energy, lightness, and feel in the feet, as well as precise positioning. The feet control the body and the hand controls the racquet and both of these extremities need to develop touch and feel. What top players are able to do is to coordinate the movements of the arms and the body and yet not make them totally dependent upon each other. In other words, even though the feet may be stepping back the arm can still be swinging the racquet forward. The hand does not rely entirely on the forward shift of the body in order to generate forward movement. This allows the body to perform its more significant role and that is to get into position to the contact point. Yet even when the feet and the hands are moving in different directions the body is still aware of what the each is doing and is able to make the proper adjustments in timing and technique so as to produce effective speed and power. This can be learned but it takes practice in using the “wrong footwork.” Instead people tend to practice only what they consider to be “correct” footwork and end up limiting their development.

Summary Even though stepping into the ball is always a good thing to strive for there are times when it simply is not possible and trying to force it to happen will only undermine the essence of a good stroke. In reality stepping in doesn't always work and other footwork patterns and stances are called for. Remember that footwork is situational and must be used to adapt to the dynamically changing conditions of play. Also realize that stepping into the ball, although helpful, isn't nearly as critical for power as rotational force, leverage, and most importantly, developing a good arm action. But perhaps of even more concern is the fact that one's overwhelming commitment to "step into the ball" is symptomatic of a very narrow approach to the game that is based on exaggerating the significance of specific and somewhat isolated stroke actions. This is typical of individuals who reduce the game down to a series of "tips" which may seem helpful in the short term but tend to blunt our understanding of the game and limit our development. Instead don't be afraid to accept the subtle nature of the game with all of its complexities and nuances and try to integrate this understanding into your stroking mechanics. Don't be too formulaic and forceful. This will lead to "mechanical play". Instead try to inject some creativity, spontaneity, and even playfulness into your game as this will help you to become a more fluid player. The "tips" approach tends to inflate the value of isolated actions and in doing so will often create erroneous associations and conclusions, and a lot of extraneous tennis talk. One of these erroneous associations is that stepping into the ball is an important element in producing power. Not only is that not true but thinking that is the case may prevent you from ever looking in the right direction and developing the real keys to speed and power – namely a live arm and good hands. In fact my suggestion to you is to take it a step further and experiment with taking your body out of the shot in order to get your hands in. Once you get your hands working you've got power at your fingertips. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Doug King's article by emailing us here at TennisOne.

Doug is one of the country's foremost tennis teaching innovators. Founder of Acceleration Tennis, a revolutionary teaching system, King is leading the way in reinterpreting the traditional tennis model. Doug King is currently Director of Tennis at Meadowood Napa Valley ( www.meadowood.com ), a Relaix Chateau Resort in St. Helena , CA . For more information on Acceleration Tennis please email Doug King at dking@meadowood.com. |

Doug King studied with legendary tennis coach Tom Stow and was a

former California State Men's Singles Champion

and the former number one men's player of Northern California.

Doug King studied with legendary tennis coach Tom Stow and was a

former California State Men's Singles Champion

and the former number one men's player of Northern California.