| TennisOne Lessons Torque of the Tennis Gods Coach Dan McCain

From ceiling fans, bicycle wheels, the blades of a blender, the hands on a clock, table saws, children's carousels and helicopter rotors to the drum in a clothes dryer, things are spinning everywhere. The earth rotates on its own axis, but also rotates around the sun. Windmills provide energy to homes and businesses around the globe when the air propels them to spin. Angular momentum, or torque is part of the basic specification of a car engine: the power output of an engine is expressed as its torque times the rotational speed of the axis. Circles are all around us — even inside the building blocks of the human body. Within most of the cells in our body, protons, neutrons and electrons rotate within an atom, and atoms spin within a cell. Red blood cells, for example, are the most common type of blood cell and our principal means of delivering oxygen to body tissues. This occurs within the blood flow through the circulatory system. It takes about 20 seconds for a red blood cell to circle around through the entire human body. Rotation is one of the cornerstones of human movement and strength. A wide range of martial arts styles emphasize trunk rotation as the strongest move the human body can make. In his book Natural Born Heroes, Christopher McDougall wrote about his time with former CIA agents who, during some initial self defense training, expanded on their discovery:

The tennis gods sync up the rotation of their shoulders and hips with the motion of the racquet head throughout the swing path. The arm that holds the racquet moves together with the rotation of the shoulders. Former ATP #1 Juan Carlos Ferrero (above right) rotates his shoulders nearly one hundred and eighty degrees on this inside-in forehand above. Nicknamed “The Mosquito” during his career due to his light, quick movement and how his forehand would so often “sting” his opponents. After his playing career ended, the mosquito started the Juan Carlos Ferrero Tennis Academy in Villena, Spain. David Ferrer attended his academy for nine months to train.

Ferrer (right) executes very similar trunk rotation as his elder statesman on this inside-out forehand. His left arm moves simultaneously with his racquet head to enhance his shoulder rotation. With his left arm parallel to the baseline and his shoulders turned further than his hips, he loads his legs into an open stance and begins his backswing. His left arm then glides ahead of his swing path, hovering in front of his left rib cage during contact. While his right arm guides his follow through, his left arm moves around his left hip, completing a stroke where his shoulders and arms moved together from start to finish. During preparation, both Ferrero and Ferrer demonstrate what the ITF reported in a Coaching High Performance Players Course that reviewed modern forehand research. To increase distance and elastic recoil and thus increase power, their shoulders and racquet rotate beyond ninety degrees passed the baseline during their backswings. Research indicated that pros rotate their shoulders approximately one hundred and twenty degrees during backswings. “Regardless of Stance, speed of trunk rotation was correlated with racket velocity,” the ITF course further demonstrated. As the forward swing begins (below right), Ferrero simultaneously springs up with the lower body and rotates his shoulders and hips through the shot. The circular rotation of his trunk allows him to strike the ball well out in front and accelerate his racquet head through the finish. The significant torque of their torsos give Ferrer and Ferrero each the ability to handle heavy, high speed shots from their opponents. It also creates the capacity for them to respond with tremendous power of their own.

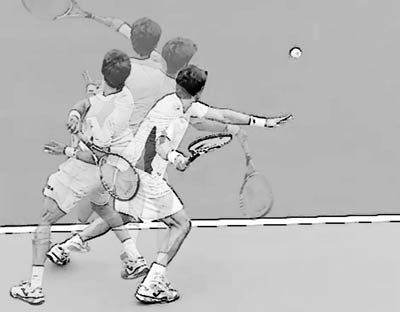

The tennis gods of today use the angular momentum of their torsos to not only generate power — they also use this significant trunk rotation to facilitate fundamentally sound racquet head technique. The circular movement of his shoulders facilitates the fluidity of their swing paths for Stan Wawrinka below. The smooth motion of his strokes results from his racquet head moving in sync with the rotation of their shoulders.

By beginning his backswing after the initial twist of his trunk, Wawrinka can each reach back behind his hips with ease before dropping the racquet head. Once he begins to drive his right hand up and into the ball (forehand side), his shoulders and hips begin to rotate forward. Because his hips open up to face the court during impact, he can comfortably strike the ball well out in front of his body. The leverage from this ideal contact point creates an added power source. Below, the trunk rotation displayed by two-time grand slam champion Li Na allows her hips to open up and face the court during contact in a very similar fashion, giving her leverage and added power.

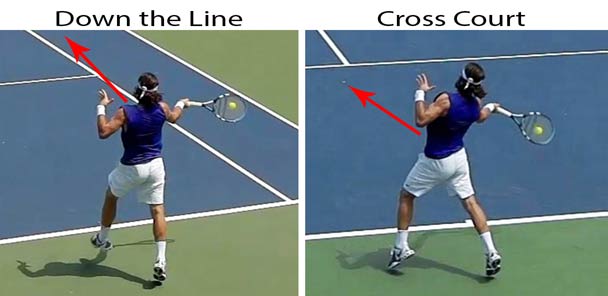

Shot accuracy is perhaps the most significant benefit of this type of trunk rotation. The ability to trust the precision of their ground strokes presents the tennis gods with the gift that keeps on giving. They can change the direction of the ball during rallies with confidence and use their instincts to move the ball around the court while constructing points. They can direct their ground strokes down the line or cross court in offensive, neutral and even defensive situations. By adjusting the timing of their shoulder rotation, the tennis gods use the torque of their upper bodies to tell the ball where to go. The difference between sending their shots to one area of the court or another lies in the amount of trunk rotation prior to contact. After winning the French Open title, former world #1 ranked Carlos Moya helped his country win the Davis Cup title in 2004 — in large part due to deadliness of his big forehand. From a distant glance in the sequences below, Moya’s first forehand sequence directed cross court and his subsequent forehand sequence sent down the line appear to contain identical biomechanics. Crosscourt

Down the Line

A closer look reveals a tangible difference. The angular momentum — or torque — or of his torso clearly shows adjustments in timing from one shot to the next. While the total amount of trunk rotation Moya displays is about the same on each stroke, the timing of his rotation serves him as a tool for accurate shotmaking.

During his point of contact, Moya literally faces his shot target with his hips and chest. Lining his chest and belly button to the court, his trunk points directly toward his intended shot destination as he impacts the ball. This allows him to have relatively the same window of space where he can make contact with the ball on all of his forehands. He never needs to meet the ball further out in front or later in his swing path to direct the ball cross court or down the line. He simply faces his target on impact to tell the ball where to go. When hitting cross court, he rotates his shoulders and hips more before contact than he would when choosing a down the line shot. Moya’s chest and abdomen point directly toward his intended cross court shot destination when he strikes the ball. When hitting down the line, he times his trunk rotation so that his chest and abdomen point down the line at the moment of impact.

The purposeful use of trunk rotation gives the tennis gods the confidence to direct their shots wherever they want and almost whenever they want. If Moya can move well enough to the shot to have the needed time and space to rotate his shoulders the full one hundred and eighty degrees or close to it, then he can comfortably change direction of the ball in a baseline exchange in not just an offensive situation, but also in neutral or defensive situations during points as well. When the tennis gods can make time to fully rotate their shoulders and hips, they almost always do. Utilizing trunk rotation for accurate shot-making grants the tennis gods the freedom to move the ball around the court in a wide variety of ways. They can hit sharp angles, change direction of the ball within rallies, drive the ball down line, or send the ball wherever they want in a wide range of situations. Typically players and coaches who lack the understanding of how to use trunk rotation for shot precision operate under relatively constricted shot selection rules. Many feel that most shots need to be hit cross court until an easier, more offensive opportunity within the rally presents itself. Changing direction of the ball during baseline rallies to hit down the line would only then be a high percentage choice. This philosophy has nothing wrong with it. However, in the heavenly place the tennis gods reside, they can freely change direction of the ball at almost any time. By timing their trunk rotation to face their torsos toward their shot target during the point of contact, the tennis gods can move the ball around the court as they see fit, rather than playing under restrictions. They can hit down the line in neutral situations with ease and sometimes even on defense. Many club players and even high performance players lack this simple tidbit that the tennis gods so easily execute. But once discovered, the notion of using trunk rotation to produce accurate shotmaking can become a religious experience for those newly experiencing it. For the fortunate new players embracing the torque of their torsos, gone are the days of timing the racquet head and contact point perfectly. Gone are the days of needing to strike the ball late in order to hit down the line, or more out in front to send the ball cross court. Gone are the days of having to guide the ball with the hands and racquet face toward intended shot targets. Present are the days of never having to think about that difficult timing of the racquet head for forehands, and having to practice endlessly to gain a sense of accuracy. Present are the days of rotating their shoulders and hips a little more before impact to hit cross court shots and a little less before contact to send the ball down the line. Present are the days of hitting forehands with nearly identical mechanics almost all the time. * * * * * Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Dan McCain's article by emailing us here at TennisOne .

Daniel McCain Daniel McCain serves as the Director of Tennis at the Cavalier Golf and Yacht Club in Virginia Beach and also as Tester for the PTR. McCain formerly served the USTA as the Manager of Player Development after 7 years of coaching Division 1 NCAA college tennis. He also served as the Director of Tennis at the Higueras-Gorin Tennis Academy and traveled with numerous players on both the WTA and ATP Tours. He is the author of Building a Champion, The I Formation, and Momentum and the 2015 released book How the Tennis Gods Move. |

When the tennis gods of today hit their forehands, trunk rotation is the engine that drives their strokes. Trunk rotation facilitates fluid backswings, ideal contact points, racquet head acceleration, and proper follow throughs. This type of torque grants the tennis gods another way to get the entire weight of their bodies driving into the ball.

When the tennis gods of today hit their forehands, trunk rotation is the engine that drives their strokes. Trunk rotation facilitates fluid backswings, ideal contact points, racquet head acceleration, and proper follow throughs. This type of torque grants the tennis gods another way to get the entire weight of their bodies driving into the ball.  The retired champion’s fellow Spaniard and pupil later became the 2014 ATP #3 ranked player. Ferrer reached the final of the French Open in 2013 and reached the semi-finals twice at both the Australian and US Opens.

The retired champion’s fellow Spaniard and pupil later became the 2014 ATP #3 ranked player. Ferrer reached the final of the French Open in 2013 and reached the semi-finals twice at both the Australian and US Opens.