|

TennisOne Lessons Don Budge — The First Grand Master Paul McElhinney Every year in the spring, not unlike the game of baseball, tennis is filled with endless possibilities. One of which, is the elusive grand slam — winning the Australian Open, the French, Wimbledon, and the US Open in a single calendar year — a feat first accomplished by Donald Budge in 1938 and that no man has accomplished since Rod Laver pulled it off for the second time some 45 years ago.

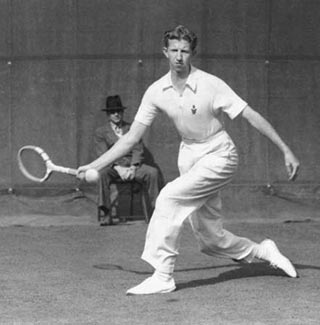

The history of tennis has thrown up many great players over the years, but sometimes in the rush toward superlatives, the term superstar can be over used, which brings me to the case of Don Budge,here, few would deny the tag is richly deserved. So, why commemorate a man who played over 6o years ago when many youngsters struggle to identify the likes of Andre Agassi or Pete Sampras, and great champions like Connors, Borg, and McEnroe are relegated to ancient history books? Let’s face it; perhaps more than any other sport, tennis has evolved over the years — so much so that the tactical game played only a few decades ago is barely a distant cousin to the power game of today. But believe me, without Tilden and Budge, Rosewall and Laver, Connors and Borg, there would be no Federer, Nadal, or Djokovic. Among men, Donald Budge set the benchmark for excellence which all succeeding generations have sought to emulate: his conquest of the elusive Grand Slam in 1938. For this alone, he deserves our attention, but in a larger sense, the game can only truly prosper if it acknowledges its roots and traditions (in an era when history and tradition are often neglected). Budge, through his demeanor, his talent, and his achievements symbolized those roots, the all-important foundations of our great game. His disciplined, professional, and power-orientated approach to the game distinguishes him as one of the founding fathers of the modern game. Unassuming and mild mannered, Budge was very much a man of his era — an era when tennis was a generally more relaxed and less ‘professional’— when it was still a game. But despite his mild manner, Budge was renowned for his ‘bulldog’ spirit, which he used to grind down opponents, particularly in long matches. Budge was one of the first to adopt a ‘power’ approach to the game, with a strong serve and volley and (untypical for the times) a very strong, attacking backhand, which he took early and hit with a slight topspin. Indeed, Budge’s rolling backhand was one of the most feared strokes of the day and helped change the way the stroke was approached. You could draw a direct line from Budge to Rosewall, to Connors, all the way to the modern one-hander hit by Federer and Wawrinka

In the annals of the game, Budge stands between the era of the great Bill Tilden, who so dominated the game in the 1920s and Rod Laver, who went on in 1962 to equal Budge’s Grand Slam achievement (and repeat the feat in 1969). Indeed, Tilden himself paid Budge the greatest accolade when he, acknowledged Budge as the greatest player who ever lived — high praise indeed, coming from the maestro himself. Many excellent players stood astride the game in those intervening years, but after the demise of Tilden and before the ascent of Laver, Budge was the name on everyone’s lips. No male player other than Laver has ever equaled his calendar year Grand Slam (although several have come close) and only three women have ever achieved it: Maureen Connolly, Margaret Court and Steffi Graf. Like so many of the outstanding players in US history, Budge grew up in the great tennis ‘crucible’ of California. Tall and athletic, tennis had to compete with a number of sports until his late teens when he devoted himself entirely to the game (in fact baseball was his first love and his smooth, left-handed swing may have contributed to the development of his powerful backhand). His springboard was the California State Boys (under age fifteen) Championship, which he won — a tournament his older brother Lloyd dared him to enter. Budge won the US Junior championship in 1933, after which he never looked back. Raised on the hard courts of the West Coast, he went on to develop a formidable grass court game; in fact grass was to provide many of Budge’s finest hours. Budge vs von Cramm His first appearance in a Grand Slam final was at the US National Championships at Forest Hills in 1936 at the tender age of 21. He lost to the already established British great, Fred Perry, in a tightly-fought five-set match. Learning from that experience, his next appearance in a Grand Slam final was in the following year at Wimbledon where he beat the elegant German, Gottfried von Cramm in straight sets. He repeated the victory against von Cramm at Forest Hills that year, a victory that teed Budge up nicely for his stellar Grand Slam year of 1938. In another famous encounter against von Cramm in the inter-Zonal finals of the 1938 Davis Cup, Budge was down 1-4 in the fifth set but eventually came back to win 8–6 in a match considered by many as the greatest battle in the annals of Davis Cup play and one of the pre-eminent matches in all of tennis history. This victory allowed the US to advance to the Challenge Round against Australia and eventually propelled the US its first Davis Cup in 12 years. Budge’s titanic struggles against von Cramm also have to be viewed in the context of history. They occurred at a time of growing concern over the rise of Hitler’s Germany, the outstanding performances of Jesse Owens at the 1936 Berlin Olympics (and Hitler’s snubbing of Owens), followed by the near-mass hysteria surrounding another US/Germany struggle, the Joe Louis vs. Max Schmelling boxing world championship bouts. Into this mix came the Budge vs. von Cramm encounters, which only added to this nationalist fervor. When von Cramm (a none too enthusiastic supporter of Der Fuehrer, as was Schmelling) was thrown into a concentration camp by Hitler some time after, Budge lobbied vigorously for von Cramm’s release, however, his appeal sadly fell on deaf ears. These events, in an era when many were confronted with clear moral choices, simply highlight how sport cannot entirely insulate itself from politics. Career Achievements

In his amateur career, Budge won six Grand Slam singles events (three US, two Wimbledons, one Australian and one French Open) and was instrumental in helping the US win the 1938 Davis Cup. Along with doubles, in total, he won 14 Grand Slam events. In his stellar grand slam year, he raced through all four finals, dropping but one set along the way — a monumental achievement. Like many of his era, he faced the choice of turning professional, which he did in 1939. He then went on to have an outstanding record in the pro game, winning the US Pro Championships twice (losing in the finals on five occasions) and the British and French Pro Championships once each. 1954 marked the end of his career after an illustrious set of achievements as both an amateur and a professional. As with some of our other star athletes, there are many ‘what might have beens. Had he not turned pro in 1939 and had not World War II broken out that same year, who knows what heights his game might have scaled on the international circuit? Another Grand Slam may have been in the cards, given his dominance of the game at the time. Despite the War, Budge was able to continue his career on US soil until the US entered in 1941. However, his new professional status, his service in the wartime military, and the suspension of European tennis during the war years, limited his exposure. So, where does Budge rank in the pantheon of tennis players? The many rankings by pundits vary, but all put Budge securely in the top ten of all time and several have him in the top five. As we know, comparing players across eras is fraught with all kinds of problems, so the debate will continue. What is clear, however, is that Budge was the outstanding player of his era. His record in the Grand Slams (including that outstanding 1938 achievement) and his performances on the pro tour put him right up there among the very best.

There was another quality to Budge, an intangible that is not mentioned enough: the fact that Donald Budge was, above all, a gentleman both on and off the court. No court histrionics or off-court playing to the media for him: but then he lived in a less media-aware era. In this, he was like a Laver or a Federer, two players also hailed for their on and off-court demeanors. Budge carried himself in a way that was both a credit to himself and to the game: an example which many of the modern era could learn from. In 1964, ten years after his official retirement, he was inducted into the International Tennis Hall of Fame at Newport, Rhode Island – a richly-deserved accolade for one of the sports all-time greats. Budge lived to the fine old age of 84. Just seeing in the new millennium, he died in late January 2000 in Scranton, Pennsylvania of a heart attack in a nursing home after suffering the lingering effects of injuries sustained in a horrific car accident in north-east Pennsylvania the previous December. Much mourned by the tennis world, his dramatic exit was a sad counterpoint to the life of a man who had experienced many dramas in his tennis career, but who led his life in a calm, dignified and mild-mannered way. His name remains to the fore through the legacy of a tennis center in Baltimore named in his honor. You wonder what his thoughts would be about this modern game of ours with its weapons of mass destruction. With his Grand Slam in 1938, Budge set the bar for others to aspire to. His graciousness toward Rod Laver when the “Rocket” equaled his achievement in 1962 was typical of the man and indicative of his mind-set that no individual is above the sport itself. Essentially, he was passing on the mantle of greatness which Tilden had passed on to him so graciously thirty years previously. Donald Budge: a true tennis champion, a gentleman and a role model to future generations — long may he be remembered. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Paul McElhinney's article by emailing us here at TennisOne . |