|

TennisOne Lessons Zen in the Art of Tennis—Mastery Kim Shanley In this series, “Zen in the Art of Tennis,” we’ve been exploring the path to flow, which we call “the zone” in sports. In Eastern culture, this path is called “the way.” Once craftsmen, experts, or athletes have progressed far enough along the way, they begin to access this ideal state of peak performance where they can “let go” and play “out of their minds.” In my last piece in this series, “Zen in the Art of Tennis, Ignition,” I discussed how we need sufficient passion and motivation to drive us far enough along this path of mastery to reach flow, to enter the zone. Perfect Practice Practice does not make perfect. Only perfect practice makes perfect. Vince Lombardi and the Green Bay Packers won five NFL championships in seven seasons largely on one play, the power sweep. Everyone knew it was coming, but no one could stop it. (The Packers’ unstoppable power sweep reminds me of Nadal’s slice serve to ad court at the French Open—everyone knows it’s coming but no one can stop it.) Lombardi broke down every movement of his players, and all the possible counter-moves of his opponents. Step by step, piece by piece, Lombardi built the most consistently effective play in football history. It was perfect practice put to a perfect purpose.

Given his gritty, all-American upbringing, building his reputation as one of the “seven blocks of granite” playing football at Fordham University, I doubt Vince Lombardi would appreciate my linking “his way” with “the way” of perfect practice as celebrated in “Zen in the Art of Archery,” or “Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance.” But one of the major threads that runs through all these stories of outstanding achievement is the concept of perfect practice. Dedication to perfect practice gives us the skills and confidence to do great things. Getting Good at Playing Bad You can practice shooting eight hours a day, but if your technique is wrong, then all So what is perfect practice? The best way to explain perfect practice is by explaining what it isn’t. It isn’t how we practice—if we practiced at all. In tennis, for example, many club players don’t practice, preferring to spend their time just playing the game. The problem with this approach is that, for a variety of reasons we’ll discuss, this “game-only” approach isn’t the best path to getting better. And even when many tennis players do practice, they spend hours simply repeating well-established and comfortable stroke patterns. The problem here—as Michael Jordan points out—we may be just getting good at playing bad.

The Rules of Perfect Practice The first rule of perfect practice is that we must practice. Not play, not scrimmage, not compete. Practice. I know, this sounds very un-American. We love games, we want to compete, and of course, we love the experience of winning. So our general cultural attitude toward practice is that it’s a form of drudgery that we’d prefer to skip over. The Practice Mindset In my essay “The Way” in this series, I discussed Professor Carol Dweck’s research that shows people with an “unlimited mindset” are more likely to overcome challenges than those with “limited mindsets.” Similarly, the path to improving quickly, according to Doug Lemov and his fellow researchers, requires the adoption of a “practice mindset” over a “playing mindset.” The Problem with Just Playing The problem with “just playing” is that we’re focused on winning, not improving. In the heat of a competitive tennis match, for example, players will revert to habits and stroke patterns they trust. If all we do is play matches competitively than what we’re doing is practicing at our current skill level. Moreover, if our form of practice is to “just play,” we don’t allocate the time or energy to examine the flaws in our technique. Without a conscious, deliberate methodology of examining and fixing these errors, which is what perfect practice is all about, we just keep repeating the same bad habits, practicing at playing bad. Chunking and Automaticity The final goal of perfect practice is perfect execution, as we saw with the Green Bay Packers’ unstoppable power sweep or Rafael Nadal’s slice serve to the ad court at the French Open. But perfect execution is reserved for the greatest at their discipline. These are the champions, artists, and zen masters of their domains. We’ll discuss how these “champion” skills are developed later in this essay. Right now we’re looking at basic skill development. The goal of basic skill development is automaticity, the ability to perform the skill without conscious thought. We try to get to “automatic pilot mode” for many reasons, including conserving energy for other conscious tasks, but primarily because we can usually perform a skill better unconsciously than we can consciously. This is exactly what Tim Gallwey’s “Inner Game” principles are all about: trying to occupy the busy-body, interfering conscious mind (Self 1), and allow the body and unconscious (Self 2) to execute without inhibiting self-criticism.

Thinking Fast and Thinking Slow There are other major advantages to automaticity (shifting to unconscious execution). Our conscious mind provides wonderful focus and great analytical tools, but it’s slow. Consciously, we think very slowly compared to the speed of our unconscious thinking. What’s the difference in speed? Gallwey says the conscious mind is a PC compared to the supercomputer of the unconscious. And as a basic analogy, this is accurate. And it’s also true that moving our athletic performance into the “unconscious mode” allows us to tap into a much faster, more powerful way of thinking—one largely responsible for the amazing athletic feats we’ve discussed in this series. Scientists have measured the processing bandwidth of conscious thinking versus the bandwidth of unconscious thinking, and the ratio is roughly 1 to 11 million. Yes, the unconscious has an 11 million to one advantage over conscious thinking when we’re just considering raw processing power and speed. According to one researcher Norretranders cites, “People’s ability to develop skills in specialized situations is so great that it may never be possible to define general limits on cognitive capacity.” In fact, in his recent book, “The Rise of Superman,” author Steven Kotler says that super-human performance is being achieved by a new generation of athletes who have mastered the skills of unconscious execution at the highest levels. We Must Practice First This does not, however, mean that the keys to superior athletic performance are simply to “let go” and “get out of one's own way,’ shutting down or overloading the conscious mind (ego) and allowing the unconscious and body to execute freely. The fallacy of letting the unconscious supercomputer run everything is that this supercomputer—at least in terms of skill development—hasn’t been programmed. In fact, as I pointed out in my “Road to Flow” piece, we begin life with the least amount of programming (instincts) than any other animal. It takes 18 plus years of training (programming) before we produce a barely functioning adult. And it takes years of practice and training before our bodies can perform complex skills at a high level. And a good portion of this training is to overcome beginners’ “natural” instincts (like beginning tennis players facing the net and holding a pancake grip to volley and serve). As Norretranders sums up in The User Illusion, “We can render our skills automatic, but we have to practice first.” Let’s Not Completely Dis the Ego Let’s face it, the “ego,” the conscious mind, gets a bad rap from nearly everyone, including mystics, philosophers and sports psychologists. And for some good reasons, as the conscious mind can “get in the way” of athletic execution. At a minimum, the conscious mind can lead to over-thinking, and at its worst, choking. But after all the negatives piled on the ego (the conscious mind) we should always remember that only the conscious mind can execute all the critical functions that keep civilization functioning: research, learning, logic, reasoning, analysis, and decision making. And last but not least, only the conscious mind can create and monitor a plan of perfect practice. As we’ll see in the following sections, what we need is a more productive alliance—not a divorce—between the ego and the unconscious to play our best. Level 1 Mastery, Basic The first level of skill mastery is really no mystery. Take learning to drive.

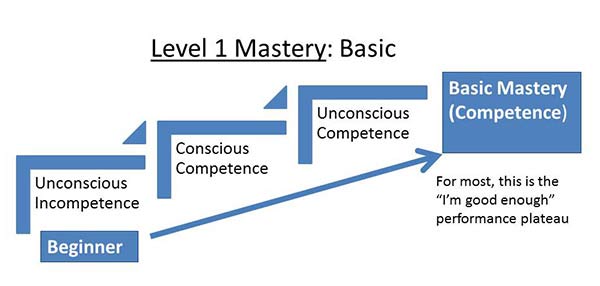

Unconscious Incompetence. As a beginner, we are unconsciously incompetent. We are incompetent—we don’t know the first thing about driving a car. And we are unconscious about this skill—we don’t know what we don’t know. Conscious Competence. With the help of a parent or teacher, we begin the slow, step-by-step process of learning the multiple skills of driving, from starting the car, to putting it into gear, to steering, to braking, to parking, etc. We are taught what is right and wrong. After a period of weeks or months of practice, we achieve a level of conscious competence. We can drive a car competently enough to pass the state’s driver’s exam, but we still have to consciously think about everything we do as we drive: “Am I going to fast? “ “Should I break now?” “Can I turn right here?” Unconscious Competence. With months of successful driving, we shift our driving into “automatic mode.” We no longer have to consciously think about all the multiple skills that go into driving (starting the car, breaking, steering, etc.). We simply get in the car and drive, reaching our destination successfully each time. We have achieved “unconscious competence.” Overly-Simplistic Mastery Model This mastery model is generally accurate in terms of outlining the path to mastery. Unfortunately, it’s over-simplistic in the following ways: “I’m okay plateau”. The model implies that once we’ve reached the stage of “unconscious competence” we’ve reached the highest level of skill mastery. In fact, we may not even be competent. Using our example of driving, how many bad drivers do you see out on the road who are driving unconsciously? Quite a few. Do they think they are bad drivers? Probably not, unless they have been given a traffic ticket by the police or they have caused repeated accidents. Too often, once we become unconsciously competent at a particular skill, whether it’s driving or playing tennis, we give ourselves a pat on the back and say, “Good enough.” This is the “I’m good enough or I’m okay” mindset that stops us from pursuing a higher level of skill. We Drop out of the Unconscious Mode. The overly-simplistic mastery model implies once we’ve moved to the “unconscious competence” stage we remain there. In fact, we do drop out of the unconscious mode from time to time to consciously think about what we’re doing. Typically, this happens when something goes wrong in our automatic pilot mode. We make a wrong turn while driving, and suddenly, we have to consciously re-group and figure out where to go. If we get a traffic ticket or cause an accident, our insurance company—or the state—forces us to go back to traffic school, return to the stage of “conscious competence” learning. In a more positive light, we drop out of the unconscious mode to analyze how to improve our unconscious execution mode. For example, to improve our tennis serve, we must return to consciously analyzing our different service actions, and then slowly, consciously re-assemble these movements into a new and better serve. We can then, one hopes, return to the mode of “unconscious competence” but a higher level of competence. Good is the Enemy of Great. This drawback relates to the “I’m okay plateau” encouraged by this model. We all have a tendency to become complacent, to believe our skill level—in whatever domain—is “good enough.” But as Voltaire said 300 years ago—and it’s been repeated by generations of writers ever since, “Good is the enemy of great.” If we are content with being good, we never strive to become great. Level 2 Mastery, Craftsman-Expert There are always a few among us who aren’t content with just stopping at the competence skill level. Let’s take a look at the craftsman-expert mastery model.

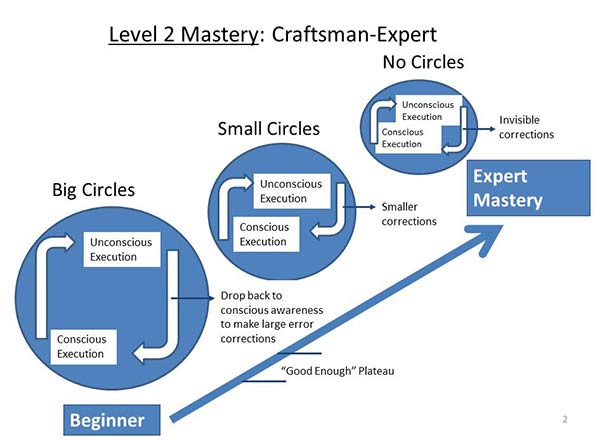

Big Circles At the beginning stage of learning a skill, we learn what Waitzkin, borrowing from his Tai Chi training, calls “Big Circles.” We move slowly and mechanically through a particular movement, like swinging the racquet through the air (shadow swinging), just trying to mimic the swing model the teacher is demonstrating. Our stroke is “big” both in terms of the physical path of the racquet as we swing it clumsily through the air, and “big” in the vague, imprecise mental model we’re trying to master: we don’t know exactly how and where this racquet should be held or swung.

In this big circle stage of learning, we spend almost all our time in the “unconscious competence” stage, trying to reach the “conscious competence” level. Since we don’t know what’s correct or incorrect, our instructor has to guide us down a path of conscious learning. And yes, this dimension of the “big circle” learning process can lead students to become self-conscious and self-critical, inhibiting their performance even at this beginner’s stage of skill development. This is where Tim Gallwey’s Inner Game principles, which provide techniques for over-loading and shutting down these hyper-critical mental processes, are most helpful. At the same time, the main thrust of the “big circle” stage of learning is to become “consciously competent.” And therefore, we can’t just tell beginners to “let go” and “get out of their own way” as the primary learning process. A beginner, by definition, is somewhat “lost” in trying to execute a particular skill, and therefore it doesn’t make sense to tell a beginner to “let go” of something they haven’t yet found. Small Circles As we improve, we move from “big circles” to “small circles.” In tennis, we move from copying the outer, big circle model of our teacher and our swing becomes smaller, more efficient. Not only is our stroke a “smaller circle” in the sense we’ve made the stroke physically more compact, we’ve created a more efficient mental roadmap on how this stroke is executed. It now becomes “our stroke,” and we’ve made it to the small circle, intermediate stage of the expert mastery model. In the early stages of "small circle" learning we begin to move from “conscious competence” to “unconscious competence.” In other words, we’ve mastered our skill sufficiently such that we don’t always have to think about how to do something to achieve a satisfactory result. Yet at this intermediate skill level, we make more errors than we like, and our execution isn’t as successful as we want. Therefore, if we want to continue to improve, we must drop out of the unconscious execution mode back to conscious examination of what we’re doing correctly and incorrectly. In the tennis world, we schedule a lesson with our pro to “tune up our game.” As we continue to improve, our circles become smaller. We’re improving faster, and learning more quickly, which means we’re shuttling between unconscious execution and conscious awareness more quickly and more productively. We learn when to “let go” and allow the body and unconscious to execute freely, but we can also drop back quickly to conscious awareness, assess our actions, and make adjustments. Once resolved on a new execution model, we can “let go” again, moving back into the unconscious execution mode, but one hopes at a higher level of competence. Getting Stuck In Small Circles The path to becoming an expert is open to everyone of average abilities, according to scientific research documented in a host of recent popular books (The Talent Code, Talent is Overrated, Outliers: The Story of Success). What stops us, then, from becoming experts? For one thing, it takes a substantial amount of time and money to continue to the path of perfect practice. Equipment must be purchased, facilities reserved, and instructors hired. These are certainly major barriers that stand in the way of becoming an expert. The other major barrier is our own mindset. Even if we have the time and resources to become an expert, we often run out of the motivation to continue to practice and improve. We may still dream of becoming an expert, but fairly soon we adopt a “good enough” mindset, and we settle into an acceptable level of competence. No Circles The hallmark of experts in any skill domain is that “they make it look easy.” Josh Waitzkin describes a long process of developing his favorite Tai Chi throw move. He first learns of it when he is suddenly flipped through the air by one of his practice opponents. Fascinated at how he could be thrown by his opponent’s seemingly invisible move, Waitzkin breaks down his opponent’s throw into dozens of tiny actions and motions.Then, in the “big circle” learning mode, he mechanically and slowly masters each of these tiny actions. Then in “small circle” mode, he begins to assemble all the pieces into one, coordinated action. Then in “smaller circle” mode, he speeds up and refines this coordinated action. Finally, at the no circle mode, he can throw his opponents in the same “invisible” way his opponent first threw him. In other words, his actions are so efficient and fast, that to the outside observer, they are “invisible.” Muhammed Ali’s “invisible punch” to knock out Sonny Liston in the first round of their 2nd championship fight is perhaps the most famous example of this “no circle” efficiency. Even spectators at ringside at the fight didn’t see Ali’s lightening quick and devastating punch that ended the fight and Sonny Liston’s career. Level 3 Mastery, Champion

The journey of the champion begins where the journey of the craftsman-expert ends. For the craftsman-expert, “very good” is good enough.” For the champion, “good”—even “very good” is the enemy of great. The champion feels he has accomplished nothing at the “very good” stage of skill mastery. His eyes are on the prize—and that prize is greatness. One Percent Solution Even beginning at an expert skill level, the would-be champion must continue to improve his game from good to great. The ascent to the summit of championship skill level takes the aspiring champion through an improvement process covering all aspects of his game, from bio-mechanics, to fitness, to mental toughness. In this ascent to greatness, the aspiring champion often returns to a compressed, hyper-intensive small circle, no circle improvement process. In this “one percent improvement” mode, the athlete melts down all the smaller circles. Lastly, the athlete “makes the move his own,” adding his personal flair or individuality to it while executing it with a “no-circle,” automatic manner. Pressure Testing Skills Learning a new skill is one thing, but trusting this new skill in competition, where there are real penalties for losing, in terms of ranking and money, is another. This isn’t only about becoming more “mentally tough.” The athlete must see that the new skill learned in practice actually works in the fire of competition. No matter how mentally tough an athlete becomes, there is no substitute for correct technique that produces the correct result—or at least the correct result often enough that the athlete trusts it and can “let go” and execute unconsciously in the big moments. Maria Sharapova, for example, is as mentally tough as any top athlete. Yet her service technique is flawed, regularly producing a dozen double-faults per match.Her superior skills and overall talents have earned her Grand Slam titles, but the arc of her championship career has definitely been lowered because she has never fixed the technical flaws in her service action. Not only must the aspiring champion pressure-test his skills, the pressure tests become increasingly more difficult at each higher stage of competition. Serving to close out a match at a challenger-level tournament is different than serving to close out a match at a top level ATP event, and different again to close out a final match at an ATP tournament. The stakes and risks continue to rise, and the aspiring champion gains a deeper level of trust in his skills and in himself. This is the reason why athletes gaining the final round of a world champion level of competition typically fail. Their skills and level of self-trust have never been tested at this extreme level. In tennis, for example, once they faced Grand Slam finals pressure, they are much better prepared to tackle the challenge the next time. In championship modes of execution, the champion has truly “let go” and turned execution over to the “super-computer” of Self 2 (body and unconscious). But this super-computer, unlike the super-computer of the beginner we see in Level l, basic mastery, has been exquisitely programmed. The great champions trust themselves and their actions in a deep way, allowing them to play in a zen state of mushin (no mind). The goal of this series, “Zen in the Art of Tennis,” has been to find the way to flow, the zone of peak performance. Here, legendary Zen master Takuan Sōhō describes the flow state of the zen master:

In my previous essay in this series (Ignition), I cited Pete Sampras’s serve as the best single example of zen master “technique” I’ve seen in tennis. A few years ago at the Bank of the West tournament in Palo Alto, California, we filmed Sampras playing in an exhibition match. Though this is more than 10 years after his retirement, you can still see the unbelievable level of confidence and trust Sampras has in his serve.

Notice how Sampras doesn’t bounce the ball repeatedly like almost every other server who is trying to gain confidence and mentally rehearse the service action. (Before he became the mushin (mindless) champion he is now, Djokovic used to bounce the ball 20 times before serving!) Notice also that Sampras doesn’t even double-check where his opponent is before serving, a nervous tick almost every other server exhibits. No, in one, languid, extended motion, Sampras casually catches the ball boy’s toss on the side of his racquet and transfers the ball into his tossing hand. He then moves into his service action, dropping his hands and bringing them back up before he begins his tossing action and flows up and through his serve—all in a completely mushin (no-mind) manner. The Battle of the Zen Masters Barbra Streisand said Andre Agassi was a zen master before the 1992 U.S. Open Final. Despite all the flack she took, she was right. Agassi, with his ability to “let go” and “see the ball as big as a basketball,” was a zen master in many of his best matches. But no one played more consistently at a zen master level during this era than Pete Sampras. In his autobiography, The Mind of a Champion, Sampras said the difference between himself and Agassi, his greatest rival, was that he played a little bit better in the big moments. And in the 1992 U.S. Open final—just like in their first 1990 U.S Open final meeting, and in their final meeting, the 2002 U.S. Open final, Pete Sampras did play a little bit better, winning the battle of zen master in all three of their U.S. Open finals contests. After beating Agassi in the 2002 U.S. Open to win his 14th Grand Slam championship, Pete Sampras, thinking he had separated himself from all other tennis champions, retired. Then along came the game’s greatest zen master. Level 4 Mastery, Hero-Artist

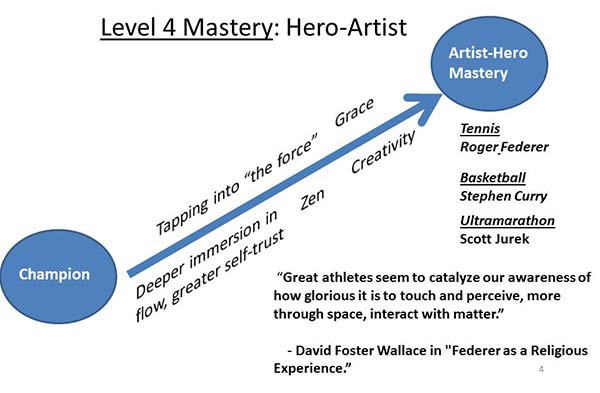

In sports, we believe once we’ve become a champion, that’s it, we’ve reached the top of the mountain. But I believe there is another level where the game becomes more than a game, when sport becomes an art. I call it, Level 4 mastery of the hero-artist. In this level, the athlete accesses more than the supercomputer of the unconscious, the analogy we used to describe the extraordinary powers of automaticity in Level 2 and 3 mastery. In the hero-artist level, the athlete taps into “the force,” all the powers of the unconscious. For my ally is the Force, and a powerful ally it is. Let Yoda have the last word for now. In the next and last essay in this “Zen in the Art of Tennis” series, we’ll attempt to climb the final steps of “the way.” * * * * * Grasshopper: “Master, what level master are you?” Take-Aways for Coaches and Parents Develop the “Better” Mindset When LeBron James was asked about his thoughts on next season after he had just won his 2nd consecutive NBA championship in 2013 with the Miami Heat, his answer was “better….we need to get better.” This is the mindset all coaches should develop in their players. It’s great to take a victory lap and savor our triumphs. But the mindset of each player, even the champion, should always be “better.” And when we lose, which is inevitable no matter how great we become, the explanation should be “we weren’t good enough—and we must be better.” After winning 8 consecutive French Open championships, Rafael Nadal lost this year. His words sum up the “better” mindset. “I always accept defeats — one thing for sure is there is only one sure thing. I need to work harder and come back stronger." Focus on Practice Not Playing Coaches need to spend most of their practice time practicing, not simply scrimmaging or playing matches. The first rule of mastery is we must practice—and practice is a very specific way called deliberate practice. This means focusing practice on the most important skills, and breaking them down (chunking), and developing specific drills and exercises to improve each chunk. Then more drills and exercises are needed to assemble the chunks into fluid, trusted, automatic skills. The final stage of the improvement process is pressure testing skills in a step-by-step, systematic manner. Developing “Goldilocks” Drills Goldilocks drills are difficult but not too difficult. The studies of deliberate practice show that the fastest way to improve players’ skills is to have them practice a skill just beyond their comfort zone. How much beyond? According to some researchers who have attempted to quantify this, they say coaches should create drills that are 4% more difficult than their players’ current skill level. In other words, the drill or exercise should be something that most players can successfully execute most of the time, but not all the time. In sum, the coach must assemble drill sequences that continually stretch the capabilities of their players. Focus on Foundational Skills To become great, an athlete must build a great foundation. Josh Waitzkin, in his Art of Learning, tells the story of competing against high-ranking young chess players who had memorized complex opening move sequences but who had skipped over the long and hard work of building a deep understanding of the underlying positional and dynamics of chess. Once Waitzkin was able to parry their clever opening moves, these boy-wonder chess players’ confidence and grasp of the match collapsed, and he would easily beat them. A deep skill foundation eventually allows players to more freely and creatively modify a skill to make it their own—and to make the game a true expression of their personality, a key to achieving the highest levels of mastery. As John Wooden said, “Drilling creates a foundation on which individual initiative and imagination can flourish.” If you’re looking for a guide in this area, TennisOne Senior Editor Dave Smith has written two excellent books on building the right tennis foundation , Tennis Mastery and Coaching Mastery. Side-Note: I wonder if the USTA’s touting of its 18 year olds winning the French and Wimbledon junior titles is another example of a system (described by Josh Waitzkin) where young players become overly-focused on winning and rankings. If you read the story of America’s last two great tennis champions, Andre Agassi and Pete Sampras, you see an enormous amount of practice time devoted to building a great foundation. The unique skills of Agassi and Sampras emerged from this foundation. What will emerge from our American 18 year old tennis champions three to five years from now? Invest in Loss

If you’ve developed the “better” mindset, then winning and losing truly becomes secondary. “Invest in loss” is a Zen principle. It means learning from everything that happens to you, good or bad, win or lose. “Invest” in this experience, detach from the result, learn what it has to teach you, become better for it. Beware the “I’m Good Enough” Mindset It’s great to admonish your players or children to not settle for the “I’m good enough” performance plateau and “to be all they can be.’ But are we living up to the same standard? Are we role models for the philosophy we’re preaching? Recent Kim Shanley Newsletters…And More on Flow

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Kim Shanley's article by emailing us here at TennisOne. |