|

TennisOne Lessons

The “Advanced Foundation”Examining the oddities of Tennis Teaching Methodology and PhilosophyBy David W. Smith (Excerpted from his book, Tennis Mastery, due out June, 2003) Are you a 3.0 or 3.5 player who has been stuck at that level for years? Perhaps even decades? If so, you are not alone! There are millions of players who seem to rise to those levels only to become permanently entrenched there for rest of their tennis careers with little hope for advancement. Why do some players move easily past such levels while others must reluctantly resign themselves to a life of tennis mediocrity? Surprisingly, it is not necessarily a lack of athleticism or even a lack of playing experience. Player progression--or lack thereof, can be traced to something more defining and, in my opinion, something that is far more revealing than genetics or opportunity. Halfway through my 30 years of teaching tennis and observing thousands of players, I began an almost obsessive quest to find out why it is so difficult for so many tennis players to improve their game past certain identifiable levels. Nearly three quarters of the current tennis playing public reside at levels deemed at or below average. In addition, over the past 30 years, an estimated 20 million tennis players quit playing tennis. One of most repeated reasons given for many of these former players was, “I couldn't seem to get any better.”

Currently, in the U.S., there are approximately 13 million tennis players, (down from a high of nearly 34 million back in 1974.) According to USTA statistics, approximately 9 million of these players are at 3.0 or 3.5 NTRP levels. This high number was not what concerned me. What did concern me was that the great majority of these 9 million players had been playing for years… many for decades! A large number of these players possessed adequate athleticism, desire and opportunity, to move past their inert levels. In addition, many of these players continued to seek tennis lessons in the form of books, videos, clinics, camps and private lessons. Fifteen years ago, I began to question why so many capable players reach levels deemed mediocre and then promptly stagnate there for basically their entire playing career.

In my mind, there is something terribly wrong.What was a telling sign for me was to watch thousands of players, most of which had been playing for many years, compete still using the same techniques they were taught as beginners. Obviously, those deemed skilled didn't play using these same methods. This distinction has created an identifiable vernacular within tennis circles. Players refer to the “Big 4-0” as being a stepping stone, a hurdle one needs to vault in order to be recognized as a skilled player. Countless 3.0 and 3.5 level players spend millions of dollars each year in search for ways to “break through” this barrier. The question is why do some break through while others have to resign themselves as “mediocre” for life? As a physical education instructor and tennis teaching professional, I became interested specifically in the way tennis was being taught compared to other sports. I read books on tennis, watched many videos and talked with fellow pros. It became utterly apparent that one aspect of the philosophy behind modern tennis instruction not only set it apart from how other sports are taught, but it also contributed to the perpetual stagnation for a great number of tennis students. Transitional Learning: The Root of Stagnant LearningTennis today is taught transitionally. That is, beginning players are often taught specific techniques that must be abandoned and changed if the player hopes to reach higher levels of skilled play. While many players are relatively successful at mastering these beginning techniques, (and usually quickly playing the game at simpleton skill levels), these achievements are often completely detrimental to subsequent advancement. Such a methodology seems to appease the student's need for instant gratification…but at a cost of their long-term development (and presumably greater gratification!) This problem is deeply rooted in several rationales. First, it is most difficult for any player to change from one method to another method within the same stroke. Any teaching pro can attest to the fervent resistance we so often see on the teaching court. When a player is told they need to change some aspect of their current stroke, their reaction is usually somewhere between denial and suicide! The second problem in making changes is psychological. Consider a player who is beginning to meet with some element of success using simpleton form. Regardless how mediocre that success may be, asking them to now change their technique—and thus digress in perceived skill level, (until comfort and confidence in the new technique is gained), is one of the hardest things for any student to do! The natural human condition of wanting to win usually supercedes and overrides the desire, and even the awareness, of using proper form in competition. And the sad part is, all those players who refuse or resist those changes toward better strokes and technique during competition still can lose! Not only do they lose, they fail to get much better in the process.

Finally, any change in an established technique will meet with physiological discomfort. It is often more comfortable for players to use fallible—but comfortable—strokes and LOSE, than it is to compete using strokes deemed proper. How to Limit Player DevelopmentI don't know too many aspiring tennis players, who are going to say, “Gee, I would love to play tennis, but I really don't want to be very good.” I suppose if players approached learning tennis in this context, then indeed we would teach methods that specifically limit player development. And yet, this is exactly how most tennis texts, videos and many tennis-teaching instructors present tennis information. Two of the most glaring examples in this practice are in the teaching of the serve and the volley. A few examples of what is being taught from just a couple books will shed some light on this problem. (Of the more than 100 books on tennis I own most say essentially the same thing.) The Serve“The grip for the serve taught to many beginners is the Eastern forehand grip. However, it is advisable to proceed to the conventional Continental grip as soon as possible.” Tennis, A Professional Guide, the Official Handbook of the USPTA “I let them use the forehand grip, (Eastern)—but always with the understanding that if they start playing well, they must change to the Continental if they want to remain competitive on their serve.” Tennis 2000 by Vic Braden and Bill Bruns

The Volley“The Eastern grip method is best used to teach the novice player, but the play should change to the Continental grip as skill develops.” High Tech Tennis by Jack L. Groppel, PhD. “The grips for the volley may be the same as those used for the groundstrokes, the Eastern forehand and backhand. They are preferred for most beginners. The Continental grip is used by most advanced players.” Tennis, A professional Guide, the Official Handbook of the USPTA These statements and others like them pose two rather perplexing questions for anyone wanting to learn tennis:

Even if players were completely capable of making the transition from basic form to a more advanced form without the frustratingly and incapacitating resistance we so often see, the second question becomes even more undefined.

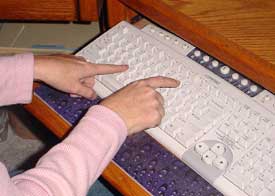

At what point does a player say, “OK, I'm ready to make a change?” One year? Ten years? This concept also creates a problematic dichotomy: if a player develops basic skills using the beginning form BEFORE attempting the more advance form, he or she will usually be so ingrained in the programmed response of the beginning form that change will be frustratingly difficult. (If not impossible!) Ironically, these two strokes I have alluded to, the serve and the volley, are the most glaring weakness separating those players who are perpetually trapped at lower levels from those who clearly advance. Typically, players can have adequate groundstrokes and even a good understanding of singles and doubles strategies. However, their fear of the net, (due to poor volley techniques) and of their serve, (specifically their second serve!), is usually the indubitable evidence resulting in their stagnate development. Foundation BuildingIf we learn to type on a keyboard or play a piano using only our two index fingers, and proceed to practice in this fashion for years, it will be very difficult to master either instrument in a manner deemed skillful. Would any qualified instructor consider teaching typing or playing the piano by finger-pecking with only his or her index fingers? Perhaps, if the student only had two fingers!

Generally, people who have not had any training in playing the piano or typing on a keyboard will try to peck out the keys on both instruments with only their index fingers. Even as they know this will not lead to mastering either device, they will not have the understanding or the training in using all their fingers in a well-coordinated or skilled fashion. (Which is why most take typing or piano lessons!) Like learning to play the piano or learning to type successfully, the concept of learning to play tennis within the field of a well-defined foundation (for ANY accomplished player), parallels the same patterns of skill-development found in most all activities. Consider other sports. Beginning basketball players are taught the same shooting techniques that the pros utilize; baseball players are taught to swing the bat and throw a ball the way accomplished baseball players do. Tiger Woods swings a 3-wood today, not much differently—in terms of technique—than he did when he was eight or ten years old. Yet, tennis books, videos and many tennis professionals teach tennis to beginners by offering introductory techniques that must be changed if the student wants to become advanced. Why? Is it that these teaching mediums assume those seeking to play tennis are so inept that they need to be taught simpleton methods before moving on to advanced? Sadly, intentionally or otherwise, this is exactly why so many books and instructors employ this philosophy. Not once, in any tennis book, do the authors mention the fact that such changes, (necessary for player advancement), will incur frustration or extreme discomfort. Nor do they mention that such changes might even be impossible for some students. To deny this fact is simply ignorance.

The idea of teaching a foundation that requires minimal change, one that allows the student to evolve within their strengths, their personality, and their preferences, is what I call the Advanced Foundation. I have found for the past fifteen years or so, that the Advanced Foundation is achievable by almost every player. I have had players go from the seemingly inept to the highest possible performance level desired. (I had one player who could not “drop-hit” a tennis ball as a freshman in high school become the top-ranked doubles player in Southern California…in one year!) Seventy year-old women have mastered the Advanced Foundation in less than a year and learned to play at levels far superior to that of women twenty years younger and who had been playing for that many years or more! I have six and seven year olds that within a year already possess strokes that most adults would not only admire but also yearn to replicate. The truth is, players who want to achieve relative tennis greatness should not be taught a foundation any different than that of social players who want to improve within the bounds of their effort! Tennis progression should not be dependent solely on player-expected outcomes. I don't know of a single golfer who wouldn't want to swing like Tiger Woods. I also don't know a single tennis player who wouldn't want to serve like Sampras, volley like Rafter, return like Agassi, or hit forehands like Roddick, Hewitt, Safin or any other top male (or female) pro.

Regardless of your particular playing ability, you can achieve relative tennis greatness. And yes, players can overcome inferior strokes if they understand three things:

In my experience, all players who have the desire can play tennis skillfully. Young and old alike can (and should!) experience the enjoyment of progressive improvement within their abilities and within their desire.

David has taught over 3000 players including many top national and world ranked players. He can be reached at acrpres1@email.msn.com. |

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about this article by

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about this article by