|

TennisOne Lessons Pro Strokes within the Advanced Foundation Are there professional strokes you can emulate? The two-handed backhand of Nikolay Davydenko David W. Smith, Senior Editor TennisOne It is often assumed that pros are so good, trying to emulate them is not only impossible, but the attempt can cause frustration and potential injury. I strongly disagree. While there are stroke components, (such as severe grips, explosive turns, and upward thrusts, etc.), that develop over time and through specific training, the form that pros use is, in most cases, far more efficient, fluid, and effortless than that which we often see on the public, club, and tournament courts around the world.

What I don't recommend is attempting such form with the same swing speed pros can be seen executing their shots. It is when the amateur, the inexperienced, or the over-zealous player tries to emulate the power and racquet head speed they perceive the pros using that injuries can result among with, quite frankly, embarrassment, and failure. When I was a kid, we did not have the resources of video tape or even computers. We emulated pros by watching them on television or in person and trying to take that memory of what we saw out on to the court. Sometimes we got it right…other times, we only thought we got it right! The point is, now we have the enlightenment of digital video tape, computer programs and web sites like TennisOne that provide a world of tennis information at our fingertips. And, today, we know more about the bio-mechanics of skilled tennis strokes which most pros utilize than we did in all previous generations. Thus, it makes total sense to try to understand and attempt to emulate these patterns of players who have been trained to get the most out of their bodies. Advanced Foundation As many of you have read from my previous articles and from my book, TENNIS MASTERY, I promote learning what I call an Advanced Foundation. Without going into great detail, the premise of this philosophy is to learn methods that specifically don’t have to change for players to reach skilled levels. Understand that there will always be an evolution in any player’s game. I can teach one hundred players the exact same strokes, yet no two will ever play exactly the same.

The point here is, that regardless of whether you emulate a specific professional, you will evolve and personalize any stroke you establish. The important point is that you are evolving and personalizing methods that will lead to skilled play. With this brief introduction to the Advanced Foundation, I will present in this series each stroke produced by specific pros who I feel are best to build your Foundation around - call it a “blueprint” for success if you will. These examples are selected because they exhibit what I would consider the most complete elements of each stroke within the Advanced Foundation. They do not necessarily represent the world’s best in terms of overall effectiveness as there are so many variables that can contribute to the effectiveness of a particular player’s stroke or shot. In fact, it is the evolution or personal intricacies that can embellish a stroke to be just that much better. But, without a proper foundation, such embellishments are not usually possible. Nikolay Davydenko: Two Handed Backhand Nikolay Davydenko is ranked number four in the world and holds wins over nearly all the players in the top ten. While he has yet to notch a win over Federer, Nadal, or Roddick, his consistency and big game from the baseline makes him a threat in any major tournament and is one of the reasons I like his backhand. Breaking Down the Davydenko Backhand: Initial Phase Grips: Nikolay uses a very conventional two-handed grip: Continental bottom dominant hand, eastern towards semi-western forehand for his left, non-dominant hand. For beginners, this grip pattern is fairly easy to assimilate and master once the grips are understood.

Backswing: Much like Lleyton Hewitt, Davydenko uses somewhat of a straight back, backswing after initiating his unit turn of his shoulder plane. There is a loop as his backswing naturally lifts the further back he takes the racquet. This relatively simple backswing pattern can help beginners to intermediate players establish a correct racquet position for topspin. A high loop, especially for beginners, often makes topspin difficult because of the need to drop the racquet head below the ball. I have seen a few pros insist on a large loop pattern, even for beginners only to watch their students fail time and time again, to get the racquet below the ball. Such players often end up hitting down on the ball and only can generate under spin—or a flat shot at best—when exposed to the loop too early in their development. Footwork: Davydenko's footwork is very conventional, much as you will see in most two-handers, the cross-over lead step of his right leg and foot, (as a right-hander would step), he transfers his weight from his back foot to his front foot while he begins to drop the racquet head to its lowest point. Beginners to world-class players should incorporate this cross-over step as it sets the body correctly to drive through the ball instead of pushing the racquet through as I will discuss in a moment.

Contact Phase Backswing: In a fluid continuation of his backswing, Davydenko tilts his wrist down which points the tip of the racquet down. This tilt down is common among almost all two-handed backhands. The degree of tilt will often dictate the degree of topspin (less tilt usually indicates a flatter ball) that a player will execute. Weight-transfer: Leading up to contact, Davydenko transfers all of his weight forward onto his front foot with his upper body becoming very quiet and upright through contact. Some skilled players execute a deeper knee bend prior to contact, but such action usually does not make a major contribution to swing speed or topspin. Footwork: As mentioned, Davydenko's weight has moved forward onto his front foot. What players need to recognize is the slight kick back of the back leg through contact. It is this move that prevents over rotation of the hips. This is one of the major errors recreational players make: They let the back leg swing out and around during the contact portion of the stroke, thereby eliminating the core of a consistent swing. Players who indeed swing this foot around open up the hips and are likely to pull the ball too far to the right (for a right-hander). This is what make a player“push” the stroke as the body recognizes they are going to be well out in front of the stroke and to counter act this, the player slows down the racquet acceleration in order to “steer” the ball in the desired direction. “Straight Line” Key Position Point

One very common element among almost all top two-handed backhands is the straight line that extends out from the dominant’s arm elbow, through the forearm and grip, and through the racquet’s mid line to its tip. This line usually starts before contact and is maintained well after contact. Players who video tape themselves can check for this position in their own backhands.

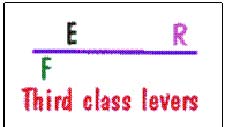

Dominant Elbow’s Pivot Point Another very common element among top two-handed backhanders is the use of the dominant arm’s elbow point as it serves as the pivot point of the stroke. If you think of the stroke as a third-class lever, (which is exactly what it is!), the elbow acts as the fulcrum, the hands at the grip of the racquet apply the force or effort, and the sweet spot is the application of this force or effort upon the ball (the resistance). You can see how the relationship of the backhand relates to the laws of motion as they relate to the use of levers. A third-class lever is used to increase the speed of the motion and this is exactly what we want to do in terms of developing racquet head speed. Follow-through Phase Body: Notice that even as Davydenko’s racquet swings or rotates nearly 360 degrees around his body, (from full backswing to full follow-through), the core of his body has only a few degrees of rotation. You can chart this by measuring how far his belly button rotates during the stroke. Even well into his finish, he maintains his hips in this sideways position until he begins his recovery footwork step. There is only about ten to twenty degrees of rotation occuring in his hips and within the core of his body.

One of the biggest problems recreational players make is that they tend to swing with their whole body. While the “kinetic chain” of movements, (the chain of muscle groups that start with the legs and ends with the hands and racquet), establishes the rotational or “angular” movements in generating racquet head speed, the core of the body will slow down or even stop to a certain degree, to allow the last “link” of the chain, the racquet, to speed up. If we were to swing only using a full body rotation, the racquet would only move at the speed in which our body was rotating. This speed is very slow when compared to the speed of what I call, “releasing the whip” by letting the arm and hands sweep through after the initial leg and hip action has been set in motion. Arm Position: A two-handed backhand is often referred to an opposite arm’s forehand. That is, for Davydenko, (a right-hander) try to picture his backhand as a left-handed forehand. I think you will see very clearly that he is no exception to this generalization. Notice he keeps his dominant arm’s elbow close to the body through contact and beyond; his left elbow, similar to his forehand, is held high through his follow-through, and his finish is relaxed and well over the shoulder of his hitting arm allowing for a long, deceleration phase of the finish.

It is not a bad drill to practice hitting forehands with your non-dominant hand only. (I suggest doing this choking up on the handle about the same position this hand would be for the two-handed backhand.) Developing the feel and control of this hand and arm will help you create a more dominant two-handed backhand. Footwork: Well after contact, the back foot—after it has kicked back—will then step around the body. This is called a “Brake Step” and helps the player push back into the court for recovery and preparation for the next shot. Conclusion If you use Davydenko’s backhand as a foundation, you will eventually develop your own backhand from a proper and prolific “blueprint!” Also, if you look at other pro’s backhands, you will discover the many similarities (as well as individual idiosyncrasies!) that exist among them. Learn to recognize the many key position points in your study of other backhands and look to replicate them in your own game! Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Dave Smith's article by emailing us here at TennisOne .

|

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about this article by

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about this article by