TennisOne LessonsPetra Kvitova: Using the Wrist on the ForehandDavid W. Smith, Senior Editor TennisOne Most individuals who have had tennis lessons have been instructed that the use of the wrist is a bad thing. In tennis, unlike badminton or racquetball (where the wrist is more active on most shots), we try to maintain the integrity of the racquet face throughout the stroke, especially within the contact phase of the shot (which is why, in tennis, we call them “Strokes” and not “Slaps,” “Flips or “Flicks”) The biggest reason we want to maintain the integrity of the racquet face (or "Plane") within a stroke is that directional control is improved when the plane of the hitting surface does not deviate much during the contact phase. Let’s look at the 2011 Wimbledon Champion, Petra Kvitova as she blends high-powered forehands with spin and accuracy. More specifically, let’s take a closer look at the role of the wrist within her forehand stroke.

The Kvitova Forehand As we look at Kvitova’s forehand, we can quickly identify many elements that are usually associated with the “Modern Forehand.” In this clip, we see her hitting from a neutral stance, and a sitting position where she does not “stand up” within the contact phase as we might see others do. It should be clearly noted here that open stances and the issue of standing up from a knee-bend position at contact are not absolutes as some instructors would insist. We see virtually all pros use all stances and oftentimes stay down for shots as opposed to thrusting upward at contact. Here, however, I want to focus on the action of the hitting arm as it moves through contact. The wrist can play a role in creating speed and spin. In Kvitova’s forehand here, we see her accentuating the spin component by using the wrist in an opportunistic fashion. But I’ll talk more about this wrist use in a moment. Pushers

One of the biggest reason players end up “pushing” the ball (directing the ball by creating a linear swing path) is that they don't retain the integrity of the racquet plane during the stroke. When a player hits harder using a swing path where the racquet face is changing at contact, the degree in which aim is hindered becomes exponentially increased. The resulting stroke preference (conscious or not) is what I call a “Gravity Reliant Stroke ”– that is, the player hits the ball hard enough and high enough over the net yet soft enough so that gravity can bring the ball back down into the court. A player who is “rolling” the racquet over at contact on a forehand or backhand groundstroke is changing the plane of the racquet face from open to closed within the hitting zone. Rolling the racquet is what many people think they see the pros do. The modern forehand especially, looks to the typical observer that indeed the racquet face is rolling over the ball. As you will see in a moment, this is not what skilled players do. For a racquet to roll over the ball, players typically approach contact with an open racquet face. Some might be more square or perpendicular to the swing path, but the racquet is usually slightly open on approach to the ball. From this point, the player tends to close the racquet face as the arm comes through the contact window, coming over the top of the ball.

The problem with this is that, not only is the racquet face changing within the important contact phase of the shot, but the racquet closing over the ball at contact does not add spin to the ball. What happens is that the ball, being only on the string bed for about three milliseconds, will already be off the string bed before the racquet has even began to roll over. Hence, the ball’s eventual trajectory will be determined not by any so-called rolling action of the racquet face at contact, but by the angle of the racquet face at the very moment of contact. if the player hits a fraction of a second early the ball will move downward, usually into the net. (Hitting early, or hitting when the racquet is more out in front of the player, will result in the ball being hit after the racquet has “rolled” more forward.) A player who is late on the stroke, hitting the ball before the racquet has turned over, will catch the ball with a more open racquet face. In either case, the ability to control the aim—and improve one’s aim—is greatly compromised by this type of movement of the racquet. Aiming becomes so dependent on the timing of the shot that most players can’t control this timing in the heat of a rally or with any repetitive consistency. The only recourse for such players is to slow the stroke down considerably or to learn to “push” the ball, thus creating a more reliable swing path but, in doing so, compromising the opportunity to hit with more pace or use angular momentum to their advantage. And so, the "pusher" or "dinker" is born! Other Wrist Movements Rolling is not necessarily a wrist movement in the real sense of a “wrist snap” as many people associate the use of the wrist with. Rolling the racquet is really pronation of the forearm, similar to the movements we see when serving. Another wrist movement is the actual snap of the wrist…or movement of the hand like the tail of a fish relative to the forearm. This movement does increase racquet head speed at contact but is usually even more detrimental to control. This type of wrist “Snap” is very common and even encouraged in sports like Badminton and Racquetball. In those sports, spin is usually not a big advantage to the shot, but speed is. In both Badminton and Racquetball, the courts are much smaller so any inaccuracy or shot variance, are not as magnified as much as they are in tennis. The Dish No, I’m not talking about satellite television! Opposite of the forward rolling of the racquet I’ve mentioned, the reverse can also occur, usually when a player is hitting a slice drive, slice volley, or drop shot. The “Dish” (or dishing the shot) is going from a more perpendicular racquet face prior to contact to a more open racquet face. Like rolling the racquet, dishing the ball changes the racquet face in the contact window. Worse yet, players often “drop” the racquet head when dishing the ball, forcing the player to hit much more under the ball than is necessary or desired. Players tend to float these shots back or simply lose control of the aiming process when they do this. Good Wrist Movements We often hear commentators remark about the wrist. Statements like: “Look at how much wrist so-and-so uses to generate racquet head speed” are fairly common. However, these statements can be misleading because they fail to identify the specific wrist-actions involved. Unlike the actions described above (rolling, dishing, and snapping the wrist), the pros tend to use wrist actions that are complementary to consistency, spin, and power. Modern forehands, especially the severe topspin grips like the Western and Semi-western, are now in an anatomical position to use the wrist in a more prolific and complementary pattern of movement than those grips usually associated with “old school” forehands. (Continental and Eastern Forehand grips.) However, players must still be ever vigilant in terms of “Keeping the Plane the Same” whenever we incorporate wrist movements in any stroke. Ulnar and Radial Deviation

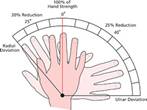

Using the wrist to create first Ulnar Deviation (tilting the hand so that the little finger moves sideways toward the forearm; the back of the hand remains flat to the forearm…no flexing of the wrist), then moving it to Radial Deviation (tilting the hand in the opposite direction, moving the side of the thumb towards the forearm, again without flexing the wrist), you can increase the action of the racquet on a forehand without compromising the integrity of the racquet face. This movement increases the action of the racquet moving up within the contact phase while keeping the plane the same within the contact zone. We are seeing more pros create additional racquet head speed in this upward direction, allowing them to drive the ball with more force, (with players swinging nearly as hard as they can without losing their balance) yet still increase topspin to bring this faster ball down into the court. Wiper Move–Fence Drill One of the analogies we use in describing the modern forehand is the use of the “Wiper Move.” This movement is the action of the racquet face being literally “wiped” up and across the ball at contact. To imagine this movement, stand in front of a fence with an open stance. After taking your racquet back as in a typical backswing, bring the racquet forward to contact an imaginary ball right where your racquet would make contact with the fence. Now, since you obviously can’t drive forward through the fence, you bring your racquet up parallel to the fence, keeping your racquet flush with the plane of the fence. If you continue to “wipe” across the fence (from right to left if you are right-handed), the racquet should finish well over to your left side. If we take the wiper move and increase the downward tilt of the racquet near the contact point of the fence, then accent the wiping motion, we naturally get the action created by ulnar and radial deviation I mentioned earlier. The hard part for most players is to integrate this wiping and wrist action with the forward swing of the racquet. Obviously, we don’t stop the swing’s forward movement like we did when using the fence drill. As the arm moves forward, the player must not let the racquet roll over the ball as described earlier. Conclusion By integrating the wiper/wrist deviation move with the forward swing or “angular momentum” of the stroke, the player can gain more topspin without compromising the stroke integrity as it applies to the racquet face interacting with the ball. This is an advanced movement all the pros are using and one you should try to integrate into your own game.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Dave Smith's article by emailing us here at TennisOne .

Dave Smith's Books on Tennis

Join thousands of tennis players and tennis teaching professionals who have mastered the game of tennis through two of the best-selling books on the game: David W. Smith's TENNIS MASTERY and COACHING MASTERY. Learn the "Advanced Foundation," the cornerstone to developing highly skilled players in both books. In Tennis Mastery, learn the philosophy, strokes, and strategies that David has used to train thousands of highly-skilled tennis players. In Coaching Mastery, discover the secrets to creating perennial championship teams and successful individuals. As one of the most successful tennis coaches in the U.S. Dave shares his secrets to building winning tennis teams and thriving tennis programs; he will show you how to train large numbers of players with minimal resources and how to attract and motivate players. Coaching Mastery is a must for every coach, tennis parent, and teaching professional. Get both books at: www.tenniswarehouse.com or www.coaching-mastery.com

David has taught over 3000 players including many top national and world ranked players. He can be reached at acrpres1@email.msn.com. |

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about this article by

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about this article by