|

TennisOne Lessons Avoiding Common Mistakes in Tennis Dave Smith The vast majority of tennis instructional articles deal with what you "should do" in terms of becoming a better tennis player. And well they should. After all, if we want to improve our abilities to play 'like the pros' (or at least within our potential!) shouldn't we know what we are striving to do?However, as a professional who has worked with over 3000 players, from junior and adult beginners to world-ranked individuals, I have seen common calamities that occur over and over, often without the player's knowledge! It's not just what they are doing wrong, but not knowing how some mistakes can keep them from reaching their potential. While errors are inevitable, the repetition of some mistakes can groove patterns or habits that are nearly impossible for many players to break. Other seemingly insignificant patterns can result in players developing strokes that completely prevent them from reaching higher levels of skilled play–even as the player may have the talent, ambition and opportunity to excel at the sport. Such potential lost is a frustrating thing for any pro to see. And often, the failure to reach a player's true potential can often be traced to some very basic flaws in their development.

Many stroke nuances can prevent progressive improvements while others cause players to resort to dinking or other undesirable strategies. Often, a simple footwork pattern at the wrong time forces several stroke, grip or swing patterns to change. Or, an improper body rotation on many shots can result in the player developing strokes that accommodate the poor timing but prohibit acquisition of more effective shots. And, when such detrimental practices occur, the player will often find it impossible to apply desirable techniques that are recommended no matter how hard they try! You might be one of those players who, when shown the correct way to hit a shot, find the method nearly impossible. While application of certain techniques might be advised, common errors in other components of the stroke make the desired method nearly impossible to replicate. Progressive Failure One of the most common mistakes players encounter is the issue of comfort. If a player starts competing using a flawed, but comfortable grip or technique, a flawed common thought is, "I'll change my technique later, after I get a little better." Huh? If I play the piano for thirty years using my two index fingers, I don't think anyone will dispute the fact that I will NEVER be a skilled piano player at any point during those thirty years! Yet, so many tennis players, using inferior strokes and grips, assume that they will somehow spontaneously acquire skilled strokes and grips! If we avoid that which we are trying to change, we will never change that which we are trying to avoid! Seldom are skilled strokes in tennis natural human tendencies. Few players can pick up a racquet for the first time and assimilate proficient strokes. Players who want to reach skilled levels of play must understand this concept. Working on patterns that are comfortable or familiar seldom leads to skilled play. (Many players can manipulate such inferior strokes to be productive at lower levels of play. But such methods or techniques fail to provide the dynamics to hit more effective shots more consistently against more effective opponents!) Thus, the first mistake that many players assume is that it will be better to change to a new, less familiar technique later. Let me tell you something: THE TIME TO CHANGE IS NOW. Whether you are just starting out or have been playing 30 years the time to change is still now. If you want skilled strokes and technique, continuing to play with inferior strokes will continue to keep you from becoming a much better player! As a litmus test for this, ask yourself this question: Have I improved my level of play in the last 6 months? If you are a 3.0 or 3.5 level player and play regularly, and your answer is no, you most likely have problems in your strokes or technique. (If you are a 5.0 or above player, the ability to improve your game falls more in the quality of the competition you are playing and the focus on more precise aim–rather than needing to make any changes in your technique.) Can an Old Dog Learn New Tricks? Often, it is the adult student who has been competing for some time who is our most difficult student. Making changes once a player has competed at some level–no matter how low that level may be–is most difficult. The perception that any change will prevent the player from competing at the level they are used to will often be the catalyst for the player to resist any change at all! While most 3.0 players when asked if they wish they could compete at the 4.0 or higher levels will respond with a resounding yes, most believe that either they aren't capable of such levels or that making such changes will take eons. Both of these assumptions are wrong! Let me assure you that everyone can make changes within a reasonable period of time. The true issues are a) belief, and b) dedication. Belief Every player must believe they are capable of reaching higher levels of play. Of the 3000 plus players I have worked with, only a couple turned out to be incapable of becoming truly skilled players. Due to health or handicaps, a few players could not physically replicate necessary tennis methods. Far more players, both young and old, have gone on to become far better players than they, or even I, believed they could! Dedication Players making changes in their strokes or techniques must be dedicated to the task. Overcoming bad habits takes will power and determination. Many of the tips and drills I will recommend in these articles will require several weeks of application. I'm not talking about hours on end everyday. On the contrary, most of the tools I offer will require only minutes at home or on the court–but on a daily basis.

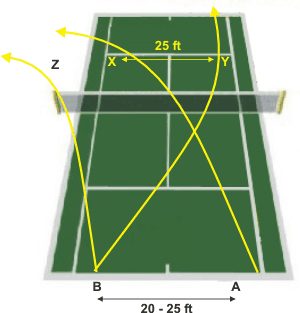

Competition The final test will be the player's insistence to only use the desired stroke patterns in competition. Reverting back to old habits will perpetuate their existence. Ironically, many players make more mistakes with their old techniques but, because of the issue of familiarity, they are more comfortable making such errors. Using new techniques will take time to become both familiar as well as more effective. This series of articles will deal with common mistakes within the major strokes: Serve, Volley, Forehand Groundstroke, and Backhand Groundstroke, and provide you with tools to overcome such errors. This first article will cover a couple significant problems dealing with the serve. Common Problems in Serving One of the most common, yet least discussed nuances, when players are learning or working on the serve, is not recognizing the necessary adjustments in position between serving on the deuce court and when serving from the ad court. It is common for right-handed servers to serve well on the deuce court but have a most difficult time hitting both effective serves as well as being consistent on the ad court. Players usually stand with their feet in the same relationship to the baseline on both the ad and deuce courts. However, the trajectory of the serve on these two sides is dramatically different. Let me explain. Let's assume a right-handed player has a natural slice serve that moves from right to left. On the deuce court, because the desired serve direction is left to right, such right-handed servers tend to serve very well on this side. The problem is, when this player moves to the ad court, especially in doubles where the server can move from 20 to 25 feet to the left, the desired direction of the serve is now left to right. However, the right-handed server who is serving a slice still has a serve that moves from right to left. The problem comes when this server doesn't adjust his body position (body stance or upper body coil during the serve), for this difference in the trajectory. And, not only has the player moved 20 or so feet to the left when moving from the deuce court to the ad court in doubles, (obviously this is far less for singles!), but depending on where the player wants the serve to land, the distance for aiming can be up to 25 feet or more of difference!

The failure to adjust the position of the feet or the upper body when serving on the ad court can force a player to flatten the serve out in order to just get it in. So, if the player has an effective slice serve on the deuce court, he or she will have to abandon the slice on the ad court because they simply can't keep it from curing too far to the left! SolutionWhen serving on the ad court (deuce court for a left-handed server), turn your feet further to the right than you normally stand on the deuce court. If you have a significant slice spin, you will want to exaggerate the position of the feet even more. You might ask: do the pros exaggerate their feet between both sides? Some do, others don't. Those who don't change their feet, instead, rotate their upper body during the toss to acquire the necessary positioning between the two sides. In watching singles players, the distance they move between serving on the deuce and ad court is usually not very far. The problem for students learning to serve well is that they play a lot of doubles. The distance between the deuce service position and the ad position can be 20 or 25 feet! This increased distance combined with the distance between serving out wide on each side will make the required change in the trajectory considerable between the two sides.

Will Adjusting my Feet Give my Serve Away?The subtle change of the feet prior to the serve is nearly imperceptible by opponents. Often the net itself hides the feet from clear view. Sometimes, players fail to recognize if their opponent is left or right handed, let alone conscious enough to look for variations in a player's stance! The real point is that those who learn to serve by attaining the stance that contributes to the desired serve will eventually learn to control such aiming and swing paths to the point they won't have to think much about the feet or make significant adjustments. However, the student who continues to practice and play and not recognizing this facet of the serve, will find reaching higher levels of serving prowess difficult if not impossible!

Other Serving ProblemsOne problem associated with the positioning problem mentioned above is the mistake of allowing the back leg to swing around. (I addressed this same issue as it applies to the forehand and backhand groundstroke in a previous article, "Stepping Through.") Because the serve is technically a forehand in terms of the general body rotation, if the player allows the back leg to swing around prior to contact, the body will not be in position to hit certain serves. This again becomes readily apparent on the ad side when an early rotation makes the player serve the ball too far to the left. Most skilled players kick the back leg back within the contact phase of the stroke. While pros and skilled players can adjust their upper body correctly and even step through early, this is most difficult to do as the player begins to add more pace to the serve. (Boris Becker is one of the rare examples of a modern server stepping through. But, Becker was able to maintain an upper body torque correctly to hit the serve the same way as if he did not step through.) Next time, I will offer some of the common mistakes seen among players when hitting the volley. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Dave Smith's article by emailing us here at TennisOne .

|

|||||||||

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about this article by

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about this article by