Designing a New Stroke

By Ray and Becky Brown

For several years, Becky and I have watched highly ranked satellite and

challenger players struggle against lesser skilled players who would throw

up a high ball as a defensive measure when they were behind, or just as a

strategy to win. In Boca Raton one year we watched as an unranked high

school player (playing their first professional event) knock off a seeded

player ranked in the 500's by mainly hitting a high ball down the middle

until her opponent crashed in frustration. We were really surprised to see

that the more skilled and experienced, seeded player was completely

neutralized by this ball. Try as she may, it was impossible for her to

defeat the high ball strategy.

|

Agassi's elbow position while hitting on the run is a significant

factor in the consistency of this shot. |

This situation, which persists today in the women's game except at the

highest levels, provides a good example of when a coach might like to

design a new stroke to improve their player's chances of going up in the

rankings.

As another example, suppose you have a highly skilled player that is

losing to lesser skilled players because when they become too nervous they

consistently put the ball in the net. There are numerous scenarios like

these when a coach can become proactive and make a significant difference

in their player's progress.

We recently decided to specifically analyze the problem the

high-ball-down-the-middle posed and develop an offensive countermeasure.

Thus we developed the type I and type II high forehands, which can quickly

put an end to this type of rally.

In the process, we developed a general method of designing new strokes

and tested the method by teaching it to some of our Pros to see if they

could do it also. We were pleased to see the method could be passed on

without great difficulty. In this article, we explain this method which we

have subsequently used to design a wide variety of new strokes for

professional players, amateurs, and handicapped players as well.

A specification for any tennis stroke

We began by determining that a tennis stroke must have three

properties, in varying combinations, in order to be effective. These three

properties are: 1) a means of providing stability to assure the stroke can

be controlled at its preferred speed; 2) a means of producing racquet

speed; 3) a means of maximizing the probably of an optimal kinetic

exchange between the racquet and ball. Any stroke having all three

properties will likely be useful. In addition, its purpose and application

should be very clear if the player employing the stroke is not to become

confused under pressure.

If these are the properties of a good tennis stroke, then what are some

of the ways these properties are manifested in the stroke? We now present

examples to illustrate each property.

Stability

What we mean by stability is that small variations in the circumstances

of the stroke do not result in the stroke becoming unpredictable. For

example, if it becomes necessary to design a new variation on the

forehand, the elbow position is a key to stability. So, if a player

prefers a severe western grip as many women do, the elbow must be well in

front of the body before rotation, otherwise the elbow will likely fly out

away from the body causing the face of the racquet to turn downward See

the three frame sequence in Figure 1 below for an example of an unstable

version of the western forehand. In this sequence, the elbow has started

even with the body plane so that as the rotation starts, the racquet face

turns downward usually sending the ball into the net.

Figure 1: An unstable elbow results in an unpredictable stroke. |

However, if the new stroke requires very little or no body rotation,

the elbow position is less critical to stability. An occasion when

elimination of rotation makes sense is when the player is so nervous at

the start of a match they cannot bring themselves to turn sideways, and

thus are always facing the opponent. As another example, if the stoke you

have in mind must be hit on the run, then considerable care must be taken

to design the elbow position to ensure stability or the forces acting on

the racquet caused by running could result in a wide variation in the ball

trajectory.

Stability is a complex property of stroke dynamics and so to work out a

stroke that is stable, one may have to go through a process of

trial-and-error. The key to stability in most cases, as we have mentioned,

is the elbow placement and its proximity to the body. For example,

movements where the elbow is close to and in front of the body are more

stable than those where the elbow is beside or behind the body at the

start of the rotation stage.

|

By combining leg, hip, shoulder, and forearm rotation Agassi is

able to generate sufficient power to hit winners from the baseline. |

Power

The second feature of an effective stroke is a source of power. This

means the stroke must have some means of accelerating the racquet up to a

useful velocity. This is the hardest specification to satisfy because the

means available to the human body to develop racquet speed are very

limited.

In general, the easiest source (but not the only source) of racquet

speed is some form or rotation. By observing someone throwing the discus

we can see that rotation can produce great speed. Thus we look to the

available sources of rotation in the human body: the hips, shoulders, and

arm.

Since a stroke should be as simple as possible, and no simpler, to

paraphrase Einstein, start with the hips or shoulder to see if they are

sufficient to produce the desired speed. This process, just as with any

engineering design, may require some trial-and-error experimentation.

Among the sources of efficient racquet velocity is the upper arm rotation.

Many players have discovered this source of power, particularly female

flat ball hitters. However, Agassi is a master of using it to produce high

ball velocity.

Maximizing the probability of a clean contact

The final specification is for increasing the probability of clean

contact with the ball or a clean kinetic exchange. This is the easiest

specification to satisfy. Any movement that will cause the racquet to move

nearly in a straight line near the time of contact will satisfy this

specification. The reason this increases the probability of a clean

exchange of energy between the racquet and ball is that a straight line is

the easiest geometrical shape for our brains to work with. Every other

shape is harder to employ.

At this point we discover a contradiction in the human makeup. While

straight lines are easy to produce and control, they are not natural

movements. Circular movements are more natural and are more likely to be

employed in swinging a tennis racquet, partly because this is one way to

produce racquet speed. But there are biological reasons why we naturally

make circular movement as well. Anyone watching a child swing a racquet

for the first time has observed how engrained and natural the circular

swing is.

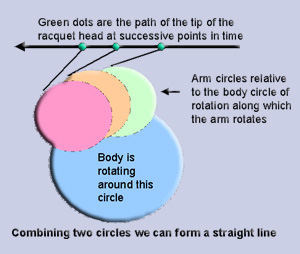

| One very subtle source is combining two rotations

to make a straight line. For example, rotating the shoulders and the

arm simultaneously can create a nearly straight line motion (See the

figure 2 on the right).

The large circle represents the circle of rotation of the body

while the small circles represent the circle of rotation of the arm

relative to the body.

If the body were not rotating, all three circles would coincide.

The three small lines represent the racquet, they are all the same

length. |

Figure 2: A near-straight line can be produced by combining body

rotation with arm rotation. |

The easiest and most traditional source of straight line motion is

produced by using the legs to shift our weight from the back foot to the

front foot without lifting either foot. When coaches encourage students to

step into the ball, this is one of the benefits they are seeking to

teach. It is a misconception to think the force of stepping into the ball

produces the resulting ball speed. It can be shown the increase in

ball velocity due to stepping forward is about 2 miles per hour. However,

the increase in velocity due to causing the racquet to move in a straight

line into the ball (resulting in a clean exchange in energy between the

racquet and ball) can be in excess of 10 miles per hour.

It is also possible to use arm rotation in conjunction with body

rotation to produce a nearly straight line interval. Why this is possible

is illustrated in Figure 2 above.

Figure 3: (1) Stabilize the elbow, (2) rotate the upper arm for

power, and (3) extend the shoulder and forearm to obtain a straight

line motion at contact. |

Now that we have set forth the basic specifications for a stroke, lets use

them to develop a high forehand using a western grip.

A high forehand is one which the ball bounces above the shoulders but is

too low for an efficient overhead. In particular, we will design what we

have called the Type II high forehand. Below are three frames (Figure 3)

illustrating the type II high forehand.

Stability comes from the elbow placement in front of the body plane as

seen in the far left frame. The racquet speed comes from the upper arm

rotation (the upper arm is roughly, but not exactly, parallel to the court

as seen in the middle frame).

|

In this animation, Becky has eliminated the leg and body components

in order to provide the simplest illustration of the three key

elements of a high forehand. |

In Figure 3, we have eliminated the body and leg movements to isolate

the arm movements. Once the arm movements are understood, one may add

other factors as desired.

The straight line interval is provided by forearm extension from the

elbow joint as seen in the far right frame. Below is an animation that

puts these three segments together as a single stroke.

In general, when designing new strokes, design the minimal stages

needed and allow the student to adapt or develop variations on the stroke

that fit their skill level and personality.

It is generally a good rule to

get the student involved in the design and experimentation process at the

start and avoid imposing ridged rules.

Also, when designing a stroke for a student, child, or handicapped

individual, first observe their natural tendencies or limitations and

utilize these whenever possible. This will greatly accelerate the learning

process.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Ray and

Becky Brown's article by emailing us

here at TennisONE.

Ray and Becky Brown are the founders of EASI

TennisTM. The EASI

TennisTM System is a new and

revolutionary method of teaching stroke technique that can dramatically

reduce the time needed to learn to play master, or any level, of tennis.

To learn more about the EASI TennisTM

System,

click here.

Ray

Brown, Ph.D. Ray

Brown, Ph.D.

Over the past ten years Ray Brown has been working in the area of

neuroscience and brain dynamics. During this time, he has conducted

extensive experiments in conjunction with his wife to determine whether

neuroscience can be applied to dramatically accelerate tennis training.

Dr. Brown received his Ph.D. in mathematics from the University of

California, Berkeley in the area of nonlinear dynamics and has over 30

years of experience in the analysis of nonlinear systems. He has published

over 20 articles on tennis coaching and player development and over 35

scientific papers on complexity, chaos, and nonlinear processes.

Becky

Brown, M.S. Becky

Brown, M.S.

Using the new training methods developed in research with her husband,

Becky Brown went from a USTA NTRP tennis rating of 3.5 to a professional

world ranking of 1,069 in less than four years. Prior to the inception of

this neuroscience research, Becky Brown had no previous high school,

college or professional experience in tennis. Ms Brown received her M.S.

in applied mathematics from Johns Hopkins University and has over eighteen

years experience in the development of high technology defense systems.

With her husband she has co-authored numerous articles on tennis training

and coaching. |