|

Features

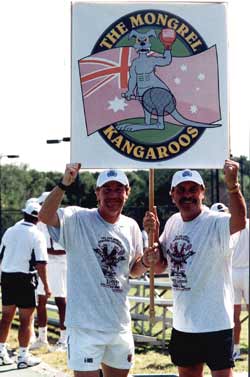

The bad news was that my opponent, Richard May, was from Texas, at ease with the conditions. As a Northern Californian, I am a weather wimp. As Richard stood to serve out the second set and square the match, I contemplated apologizing to my teammates for losing 14 straight points. We’ll return to this match shortly, but first let me tell you where this near-catatonic episode occurred. Welcome to Tennis Fantasies with the Legends, held at the John Newcombe Tennis Ranch in New Braunfels, Texas (30 miles from San Antonio). This is the only tennis fantasy camp in the world. I’m not talking about a few hours batting balls and playing hit-and-giggle with some pros. I’m talking about a high-octane, beer-swaggering, ball-bashing, blarney-spewing week of fun and games with 80 men (yes, it’s male only) and a dozen all-time greats. The headliners featured in Tennis Fantasies’ marquee include such Hall of Famers as Australians John Newcombe, Roy Emerson, Fred Stolle, Tony Roche and Mal Anderson; ESPN analyst Cliff Drysdale; former US number one Charlie Pasarell; Aussie doubles aces Owen Davidson and Ross Case, Americans Bobby McKinley, Dick Stockton and Marty Riessen. Others who’ve joined in over the years include Ken Rosewall, Manuel Santana and Mark Woodforde. Those all-timers are considered “The Legends.” And yet, as camper Ken Munson joked my first day on the camp’s courts, “the real legends are the guys who come back here every year.” Each year, more than half of Tennis Fantasies’ attendees are repeaters. As time will tell, Munson’s humor proved prophetic. When I first heard of Tennis Fantasies in 1988, I was immediately drawn to this Aussie confab. I loved the way the Australians legitimized tennis. In America, the good tennis player is considered a little tennis geek, closer to an elite wiener of a music prodigy than a jock. Not so in Australia, where the spirit of tennis seems more like American softball – robust, athletic and, best of all, inclusive. Humbled in the presence of greatness, at Tennis Fantasies, we are all schleppers. Don’t worry – everyone gets plenty of competitive tennis. But in the morning, when it’s time to warm up, you better be willing to hit with anyone of any playing level. Dare beg off in snobby hopes of hitting with someone else, and you will be publicly humiliated by Roy Emerson (who himself will hit with anyone anywhere). “You guys think you’re the good ones at your club,” barked Newcombe, “but let’s see what happens when your mates are counting on you to win.” My affection for Aussies had crystallized years earlier, on a summer evening in 1974 when I was 14. My older brother and I were attending a World Team Tennis match at the Los Angeles Sports Arena. Tennis gym rat that I am, I insisted we arrive early for practice. Sneaking closer to the court than the ushers would permit (a technique I continue these days as a journalist), I shuffled near the back of the court and watched Aussie John Newcombe whack his serve. Next to my fellow lefty, Rod Laver (then fading), the swashbuckling Newcombe was my favorite player. Newcombe kept banging his serves into the carpeted court. Seeing a ball roll into a corner, I walked to pick it up. Staring at it, I considered putting it in my pocket. While contemplating my petty theft, Newcombe saw me holding the ball. I was caught. And stealing the materials of a pro at that. I’d have to mutter some apology and shrivel up to my seat.

“Go ahead,” said Newcombe. “Take it.” What? “Take it, go ahead, take it.” Unbelievable. The ball sat in a dresser drawer for three years. So when I at last made it to Newcombe’s Fantasy Camp in 1995, I was eager to make that classic connection. It’s a story repeated across all sports – from baseball lovers meeting Willie Mays to footballers encountering Johnny Unitas to hoop dreamers with Jerry West. Boy has hero, boy meets hero as a man, boy exchanges friendly vibe with hero. You would be tempted to call my eventual linking with Newcombe merely a tennis version of this classic tale. And you would be right. But only partially. I have now attended Tennis Fantasies for seven years. My rookie year – and make no mistake, newcomers are indeed referred to as “rookies” and expected to perform on and off the court – every day featured an unprecedented ball-hitting experience. A volley drill with Stolle and Roche. A doubles fantasy match with Emerson as a partner. Newcombe watching me close out a 5-4 game. Davidson and Riessen running me through an approach shot-volley drill. Stockton hoisting lobs. Drysdale screaming his two-hander at my throat. Rosewall and Anderson, relentlessly humble, ballboying. As a rookie, my intentions were, in retrospect, rather perverse. I wanted to prove to these great players that I could play good tennis. Hey, I’m a 4.5-5.0 player. I’ve played tournaments, and even won a few. Gee, didn’t I make All-City in Los Angeles back in 1976? This goal was shared by other players, some better, some worse, ranging from college lettermen to fairly mobile seniors. Looking back, I realize that the objective had two odd sides to it. On the one hand, it was misguided, downright lame when appraised seriously. Would a Sunday painter dare try to impress Picasso? What would Shakespeare make of an accountant who once took a creative writing class? Should a lawyer be dazzled by a guy from the debate team? But here we were, those of us who at best were what I call good crappy players, trying to show men who’d played Davis Cup that we had the goods. At least I know that was my partial intent. But on the other hand, there is something wonderfully indigenous to tennis that makes this objective captivating. “You can’t really play football or baseball too seriously, but you do play tennis, and you hopefully do what you can to take it seriously, enjoy it and improve,” Emerson said one afternoon while a group of us gathered around him during lunch. “And what matters to me in competition is not so much the standard of play as the quality of effort that goes into a single match. I like effort. How supposedly good or bad you are has nothing to do with it.” Tempting as it is to attribute Emerson’s democratic beliefs to his generation – I’ll bet my life savings that neither John McEnroe nor Andre Agassi thinks this way – I’ll go a step further and say it’s particularly cultural. Many of the Americans I’ve met from Emerson’s vintage tend to treat us schleps with moderate condescension.

The reality is quite different at Tennis Fantasies (verbal contrast intended). Year after year, I’ve watched Emerson, Newcombe, Stolle, Drysdale, Riessen and others absorb this effort first-hand as they stroll from court to court watching us campers play one another. After a day and a half of clinics and practice, Tennis Fantasies revolves around three days of team matches. Campers are drafted on to one of four teams. Each of the three days we play a singles and a doubles match. Our common link is our love of tennis. My doubles partner, for example, is a gentleman from Queensland, Australia named Angus Deane. Angus owns a ranch that covers approximately 300,000 acres, so far in the bush that he flies across it with his own plane. I live in a studio inside a condo in Oakland, California. Angus makes Crocodile Dundee look like a shrimp. At 5’-8”, I am a shrimp. Righty Angus loves to crack the ball a country mile. I’m a lefty who plays a game that mixes Brad Gilbert and John McEnroe (“spinning ugly”). “First to the net, first to the pub” is the Aussie motto Angus tries to match. I’m only good at the first half of that statement. Nowhere else but Tennis Fantasies could a collaboration like this happen. But while collegiality is one aspect of Tennis Fantasies, I want to return to competition. Listen to the tale of another camper, Mark Benjamin, a mild-mannered pulmonologist who once blew a 6-0 lead in a conventional tiebreak. Compounding Mark’s woes was that his collapse was witnessed by 40 campers and every one of the Legends. Moments after Mark’s loss, sitting on the bench in a distraught heap, a coach come to his bench. “Bad luck, Mark,” said Charlie Pasarell. “It happens. Believe me, it happens.” Only two nights before, Pasarell had told the tale of his Wimbledon epic with Pancho Gonzales, a five-hour-plus saga where Pasarell lost seven match points – and, eventually, the match. Later that night, Emerson examined the tiebreak with Mark with the same rigor he’d bring to a Davis Cup match. By the time it was all over, Benjamin was more than a guy who’d lost a match. Merely for his courageous efforts, he was a champion. As the saying over the doors to Wimbledon’s Centre Court reads, “If you can meet with triumph and disaster, and treat those two imposters just the same.” Over the time, over the years, all who come to Tennis Fantasies begin weaving a common tale – a massive tapestry of matches won and lost, comebacks successful and failed, leads gained and squandered. The Davis Cup epics of Emerson and Stolle begin commingling with camper tales. A doubles team is somewhat jokingly compared to Newcombe-Roche. Another camper is compared to Beppe Merlo, a difficult Italian claycourter of the early ‘60s.

In the process, a new folklore is developed. Champions allegedly cannot accept losing. But I’d argue the opposite. Those who’ve fought the biggest battles know all about losing. They’ve done so at the highest level, for the highest stakes. Then they come back again, and again, and again. That appetite for the struggle is precisely what the likes of Newcombe, Pasarell, Stolle and the rest so enjoy about us campers with our homegrown strokes, woeful footwork and sporadic concentration. Our efforts, motivated under their watchful eyes, turn us into champions. With greatness gazing at us, it would be shameful if we did anything less than give our all. So back to the court, and my imminent collapse. Richard May was punishing the daylights out of my second serve, absolutely brutalizing me with his forehand. In the meantime, my own forehand was getting tighter with each point. Richard’s coach, Stolle, told him to keep going after my forehand, which each point was resembling more of a poke than a stroke. Meanwhile, Newcombe watched in agony from a distance. If you had told me back at the LA Sports Arena in 1974 that this guy would eventually watch me play 30 matches I’d have thought you were nuts. But here he was, witnessing me push, run and scrape through these points. Serving for the second set at 5-4, Richard held at love. With the tiebreak at hand, I borrowed a technique from my college days. Just like an exam, I knew there was likely a finite amount of time left. Fifteen minutes is all we need, I told myself. All we need are 15 good minutes of concentration – and one way or another the match will end. Focusing like this once helped me get through an essay on Andrew Jackson. Why not with Richard? A bad forehand error from Richard gave me a 2-0 lead. Poking forehands, caressing backhands, sneaking into net, I went ahead 5-1. As we changed sides, my teammate, Kevin Castner, encouraged me with the words, “Halfway home.” Then Richard ripped a ballistic forehand winner and, worse, a dropshot that made me look pathetically slow. It was now 5-3. In between points I could barely walk. I’m not trying to sound like some Connors-like demagogue, but unquestionably something about the humidity and this being my 4th long match in two days and who knows what else made me feel more dazed than I’d ever been on a court. I can’t even remember the next six points, but I reckon there was a fair amount of scrambling, more of my off-pace shots, a couple of random volleys, and there I stood, serving to Richard in the ad court at 9-5. Momentum has a funny way of shifting in these tiebreaks, so I knew I wanted to make the first match point the last. The bad news was that my lefty wide serve in the ad court had been nullified by Richard wisely standing virtually in the alley and daring me to go to his superb forehand. What to do? I remembered words I’d heard from Newcombe years before: On a big point, serve into the body, and then, as he once said to me in the ranch’s “Waltzing Matilda” room, “You must have faith in your volley.” Not confidence, but theological, spiritual faith. I loved the mystical qualities of that concept, the way it was bound more in emotion and the heart than anything obviously tangible. So instead of striking the classic lefty can-opener, I spun one into Richard’s forehand, hoping he’d drive one to my volley that I could push into a corner. Instead he hit it inside-out five feet wide. Sitting down after shaking hands, throwing out the five water bottles gathered under my chair, another camper came up to me. “You know, we all come here for a good time, but I must say, you play the way you’re supposed to,” he said. “You left it all on the court. You gave it everything.” I told him if I had any liquid in me I’d have cried right then and there. That’s when the true lesson of Tennis Fantasies hit me – and it’s one applicable on all courts, no matter if you’re being watched by an Aussie Hall of Famer or no one at all. We recreational players will spend our entire tennis lives attempting to master stroking techniques these world-class players had inhaled by age ten. The sober reality is we won’t get there. I once watched Dick Stockton demonstrate something as simple as a forehand volley grip and realized I didn’t even know how to repeatedly do that with exceptional proficiency or body awareness. But one thing I do know: Anyone, at any level, can muster up world-class intensity. And with a little more brainwork, that intensity can be wed to a reasonable degree of strategic and tactical insight. The bodywork is a never-ending process. But head and heart can be engaged immediately. The American Heritage dictionary defines “legend” as

Make no mistake: The names on the Tennis

Fantasies poster are the obvious legends. But over the course of

attending this camp I’ve also come to see that it’s possible for

anyone to become or make a legend – and somehow believe in the value of

his or her own life’s plot line. This fantasy camp carries

deceptive reality if you’re open to it. P.S. – The next day, I lost a singles match, 6-1,

6-1. Triumph and disaster, right? For more information about Tennis Fantasies, contact Steve Contardi at 1-800-874-7788. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about Joel Drucker's article by emailing us here at TennisONE.

|

Last Updated 1/15/02. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved. |

|||||||