The Evolution of Tennis Strategies

by Dave Smith

|

Players like Agassi have shown the return can be an “equalizer” to

today’s powerful serves. |

Like it or not, the game of tennis has changed over its historical

course. Some say for the better, others are not so sure. Certainly the

game’s general popularity has seen several highs and lows over time. Some

rationalize that the game’s shifting popularity is based on these

evolutionary changes…namely, changes in power and, consequently, changes

in strategy.

There seems to be a split among tennis enthusiasts on whether or not

these changes are good for the game: On

one side are those who favor the “old school” cat and mouse

strategies predominately centered on slices, finesse shots, and approach

and volleys. On the other side are those who favor the modern game of

powerful serves and groundstrokes interlaced with volleys, drops and

angles.

I have received passionate pleas from individuals favoring a return to

“traditional” strategies of chip-and-charge offensive game plans or

serve-and-volley strategies. The greatest complaint expressed, is the lack

of interesting points, especially in men’s tennis.

Certainly, over the course of the last ten or fifteen years, men’s

tennis has evolved into a serve-fest, with many points being determined

quickly, usually with a potent serve and an occasional volley or

groundstroke winner or forced error. However, the last couple years have

ushered in yet another subtle shift. It appears that the effectiveness of

the return-of-serve has caught up to that of the serve, allowing the game

to evolve back into points that include rallies, exciting ones at that!

Even on fast surfaces such as the grass at Wimbledon, rallies once

again are in many cases becoming the norm as opposed to the exception.

Despite the plethora of big servers like Sampras, Roddick, Safin, and

Ivanisevic, rallies at Wimbledon and other Grand Slam events have become

longer and more exciting.

|

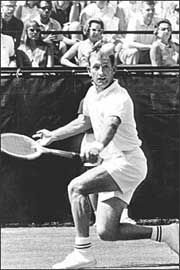

Players up to, and including, the McEnroe era relied heavily on the

slice to set up points. Today it's used as a defensive tactic or as a

change of pace. |

However, the game today is played differently then it was when wooden

racquets ruled the court and grass was the predominate surface. The longer rallies described include a barrage of incredibly

powerful groundstrokes and serves, spectacular topspin angles and displays

of incredible athleticism and conditioning unimaginable even a few years

ago. Subsequently, the strategy of the game has changed from the days of

‘chip and charge’ to a more resolute game of cat and mouse played between

players who posses weapons of mass destruction!

In Part 1 of this series, I

discussed the evolution of tennis strokes and the development of the

topspin groundstroke as being the root of tennis evolution. Players who

wanted more power needed a technique to help keep more powerful shots

in play. Of course, the answer to that problem was topspin. Understanding

the physics of spin can help us understand the how and why of changes in

tennis strategies.

The advent and propagation of greater topspin on groundstrokes has had

a significant impact on how the game is played at the pro level. On the

other hand, the “traditional”

shot-of-choice, the slice, has seen virtually no change in its

presentation for perhaps one hundred years. The simple physics of the

slice makes it almost impervious to the kind of changes we have seen

associated with topspin shots.

One of the contributing factors for the slice becoming less a weapon

and more a situational stroke is the change in court surfaces. Prior to

1975, three of the four Grand Slams (U.S. Open, Australian Open, and

Wimbledon) were played on grass. Since the fast surface of grass arguably

favored net-attacking strategies, most top players adopted this style of

play. (I say arguably since Bjorn Borg, a baseline player extraordinaire,

ruled the grass at Wimbledon in winning 5 of his 11 major titles there!)

However, today, the only Grand Slam event still played on grass is

Wimbledon.

With a variety of court surfaces, from hard courts to grass, from

synthetic surfaces to clay, players today must be able to adapt and devise

game plans that not only work for them, but work for the playing surface

as well.

How has this consequential shift in groundstroke preference led

specifically to the changes in tennis strategy? Before we can address this

question, we must clearly identify what those strategies are.

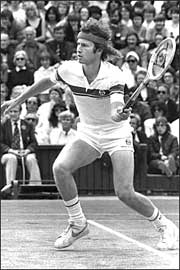

Attacking players of past eras; Ken Rosewall, Rod Laver, and John

McEnroe all featured game strategies that centered around getting to the

net. |

Strategies of Tennis

For simplification, tennis can be reduced to two basic strategies, attacking and retrieving.

Attacking strategies include two distinct tactics:

|

It really wasn’t until the late 1960’s that Billie Jean King

demonstrated women too could be aggressive net players |

- Serve and volley

- Chip and charge

Most players of the past executed game plans that revolved around these

two strategies including Fred Perry, Jack Kramer, Pancho Gonzalez, Don

Budge, Ken Rosewall, and Rod Laver.

Traditionally, women did not attack

the net as often nor with as much aggressive style as men. It really

wasn’t until the late 1960’s and early 70’s that Billie Jean King and

compatriot Rosie Casals demonstrated that women too, could be aggressive

net players. King, Casals, the Brit, Virgina Wade, Australian Evonne

Goolagong and especially Martina Navratilova, set the stage for other women to play a more aggressive, all-court style of

play.

Certainly, a host of champions have utilized this attacking strategy

within the past three decades. Perhaps beginning with Stan Smith, players

like John McEnroe, Arthur Ashe and Stefan Edberg led

the way for the likes of Pete Sampras, Boris Becker, Patrick Rafter and

Tim Henman to make their marks as aggressive net-seeking attackers.

The more defensive “retrieving” style of play can be characterized by

players camping out at the baseline, typically waiting for their opponents

to make a mistake. Notable players who have successfully utilized this

game plan include Bjorn Borg, Michael Chang, Chris Evert, and Tracy Austin. Even a young Andre Agassi played

this decisively baseline game.

|

Players like Chris Evert (left) and Tracy Austin preferred a more

defensive, retrieving style of play. |

Strategies Today

Top

players of today possess such massive topspin groundstrokes that they

often make playing the baseline an aggressive “attacking” game in itself!

Never has there been so much power addressed to balls from behind the

baseline. In my opinion, this power from the backcourt has brought about

the greatest change in player strategies.

Topspin Versus Slice

As I have mentioned, topspin mechanics have taken on new levels of

offensiveness making it much less certain that a player can stroll up to

the net and effectively put away a volley. And, far less often today do

we see the slice utilized strictly as an approach shot.

The slice is still used by most players—including two-handed

backhanders (using one hand in most cases)—as both a defensive stroke as

well as a change-of-pace ploy. However, as the power of groundstrokes and

passing shots continue to intensify, the specific net-attacking only

strategies of the past are becoming more of a liability for those who attempt them.

For this reason, the

evolution of tennis has gradually moved away from the dominant net-attacking

strategies of the past into a more methodical dissection of opponents through

the weaponry of imposing groundstrokes. Only then, when players get their

opponents in trouble through a course of spin-related power mixed with

geometric placements, will they venture to the net for the anticipated

volley winner they so richly deserve.

|

Bjorn Borg maintained a steel-like

patience opponents found tough to crack. |

Simply playing a retrieving singles strategy, where players camp out at

the baseline and engage in a slugfest of groundstrokes, has proven to be

somewhat limiting among many of the top up-and-coming players. Much like

playing a strategy that consists predominately of serve-and-volley or

chip and charge points, hanging back and hitting groundstrokes almost

exclusively has become less successful in today’s professional arena.

I

remember watching how uncomfortable past baseline players became anytime

they approached the net. Not so long ago, Michael Chang looked like a fish

out of water when forced to come up and volley. Ivan Lendl liked to stay

back with patience and topspin as his main weaponry. He too did

not look comfortable during times he would approach the net until

later in his career. Ironically, even as Chang developed a respectable net

game as his career proceeded, he never gained the kind of success he

enjoyed when he was strictly a baseline retriever.

Notwithstanding, the vast majority of men and women tour professionals

today play a more identifiable “all-court” game. Their volley winners

often occur after a chess-like series of powerful, precision groundstrokes

open up the court. Few champions of

today’s modern game have been able to win consistently without some mastery

of all

the weapons available.

|

Even extreme groundstrokers like Andy Roddick have to adapt to an

all-court style if they are to advance up the rankings. |

In many cases, these heavy-handed topspin groundstrokes force a point

to end even before a weak shot is parlayed into a winning volley. Thus,

many people might consider this strategy as a “baseline-only” contest

when in fact, it is a constant battle of respect and confidence between

very skilled performers who can play the whole court with

expertise.

Players who could be arguably labeled as “All-Court” players include

Taylor Dent, Tommy Haas, and Roger Federer. Andy Roddick appears to be

making a move to become a more offensive net-attacking player in recent

months.

On the women’s side, we see very few true net-attacking strategists.

However, with the possible exception of Monica Seles, most all the top WTA

players can and do play the net when presented with the opportunity. Top

ranked players such as the Williams sisters, Henin and Clijsters, and even

the slumping Capriati and the vanishing Hingis possess excellent net

skills and strategies to go along with their topspin power from the

baseline.

Racquet Technology

One last contributing factor to the evolution of tennis strategies (and

certainly not the least!) is the revolution of modern racquet technology.

The influx of ultra light, powerful tennis frames seems to have ushered in

a new physical component to the modern game. The self-limiting speed of

shots due to the seemingly restrictive power of wooden racquets has given

way to a nearly freewheeling sense of power through racquets constructed

of space age materials. These lighter, stiffer racquets allow players

(particularly in the women's game) to generate much faster racquethead

speed which leads to an increase in the amount of topspin pro players can

create. More topspin can equate into substantially more power in the

topspin groundstroke game.

Even as these advanced racquets have helped create serve speeds

unimaginable a few short decades ago, current players are reluctant to try

to advance themselves to the net following such potent initial shots. This

says a lot for the respect for the return of serve and groundstrokes in

general. It makes sense: The same racquethead speed generated on serves

due to racquet construction is also available for use in returning such

shots.

Conclusion

So, is the serve and volley game gone the way of the dinosaur and the

eight track tape? Perhaps not. Tennis is a dynamic game and strategies as

well as players will continue to evolve. As players discover new ways to

combat present tactics, popular strategies of today may become historic

strategies tomorrow. And strategies of the past may indeed come full

circle and become strategies for the future!

Next Up

In Part 3 of this series on the Evolution of Tennis, I will

discuss the evolution of the backhand, specifically addressing the change

from one hand to two and the different types of two-handed backhands that

we have seen among top players.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about this article by emailing

us here at TennisONE. Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about this article by emailing

us here at TennisONE.

David W. Smith is the Director of Tennis for the St. George Tennis Academy

in St. George Utah. He has been a featured writer in USPTA’s magazine

ADDvantage in addition to having over 50 published articles in various

publications. David has taught over 3000 players including many top

national and world ranked players. He can be reached at ACRpres1@msn.com |