|

Mental Toughness

The

answer is, we do not know for sure! When it comes to tennis psychology,

much still remains a mystery. In fact many of the things you've heard

about tennis psychology and mental training may actually be false or

half-truths at best. Myths in tennis psychology are just as prevalent as

myths surrounding the technical/tactical/physical side of the game, if not

more so, with tennis and sport psychology being in the infant stage when

it comes to research of its key concepts (e.g., intensity, visualization,

body-language, control of thoughts). Nevertheless,

despite the tenuous nature of many of the key concepts, interventions, and

common advice in tennis psychology, they continue to be propagated as

though they were the gospel. Worse yet, sport psychologists rarely monitor

or study the efficacy of their interventions, advice, and "pet"

programs. Practitioners in sport psychology are often so convinced of

their dogma, they have actually "brainwashed" themselves and

their clients into believing they have the answer and are capable of

turning your mental game around. Unfortunately,

this has led to a credibility problem in sport and tennis psychology, and

although the field is booming in terms of the number of practitioners that

are jumping on the "I'm a mental performance enhancement expert"

bandwagon, studies indicate that fewer athletes, including tennis players,

are buying into sport psychology and many of the myths perpetuated by the so-called "mental experts." For example, Klaus Lufen found in

surveying all of the top 200 men and women professional tennis players,

that although over 90% believed the mental side of tennis was crucial to

success, only about 3% of these athletes engaged in any form of

psychological training. Why? Because after discovering that various forms

of psycho-"voodoo" had no readily discernible effect on their

performance they stopped engaging in specific forms of mind-training and

in most cases "fired" their psycho-gurus. Anecdotal

evidence in the form of an informal survey by Dr. Jim Taylor, a sport

psychologist, supports the hypothesis that athletes are not really buying

into what sport psychologists are selling. Dr. Taylor's survey found that very few

sport psychologists earn enough money to support themselves by

practicing Sport Psychology; suggesting, not enough athletes, coaches, or

teams are willing to pay the big bucks (or any money in some cases). They

are essentially saying, "Show me it (mental training) Although, I have painted a dismal picture, there is hope, both for athletes and sport psychologists. However, the field of sport psychology needs to be shaken up. Tennis players and coaches must become critical thinking consumers of sport psychological advice. Sport psychologists must base their advice on sound scientific data and not perpetuate myths and self-generated unproven protocols to improve performance, all the while selling themselves as mental messiahs. In scanning web sites of even highly

qualified practitioners one finds self-embellishing propaganda. Doctoral

level psychologists calling themselves the "future of sport

psychology," or "Arizona's secret weapon," (their

psychologist), or "the doctor who'll put you in the zone" are

some of the more modest slogans youíll find, with many sport

psychologists selling a cult-like guru image marked by excessive claims,

crass self-promotion, and gross egocentricity. In the end the client

suffers, with a backlash to be expected, as is already underway, with the

field of Sport Psychology continually losing more and more credibility. So dear reader, remember, no matter who says what, regardless of how famous they are, how many times they have been on TV, or who they have worked with, Only the truth matters, (an elusive goal [the truth] in sport psychology), and finding the truth starts with dispelling myths and learning to approach your own mental game from a critical and even skeptical perspective. The 8 Myths of Tennis Psychology!1. "Tennis is 90% mental" (Boris Becker among others)Although it would be hard to argue that tennis is not a mental game, it is by no means mental 90% of the time. Before accepting such a claim one must define what "mental" means. If we deem the scope of mental activity to include perception-action relationships one can readily claim tennis to be even 100% mental. However, the scope of the definition of "mental" usually is limited to processes and mechanisms such as personality, concentration, motivation, etc. From this perspective studies have consistently shown that psychological (mental) factors rarely, if ever, make up more than 10% of the variance in the tennis performance equation. That is, if there were 100 variables making up performance, only 10 of these would be psychological. My most recent research, however, does

indicate that during critical moments of competition psychological factors

do contribute more than 10% to the performance equation. The bottom line

though is that trivial statements such as "mental factors make up 90%

of tennis performance" are just that, trivial statements that are

rendered meaningless without scientific support. In other words, "so

what!" What does it mean to know this? Should one even accept

inaccurate and vague statements? Will knowing this help you reach the 90%

level? 2. The "16 Second Cure" (Jim Loehr)

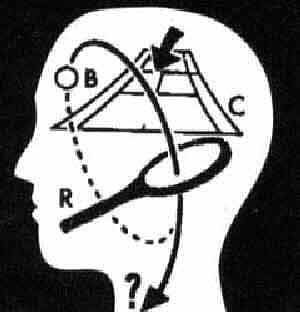

The "16 second" cure is a ritualistic recipe that supposedly helps players compose themselves between points. By engaging in a scripted routine of consciously regimented movement, body language, and internal thoughts it is hypothesized a player will be better ready to contend with the upcoming point. Sounds plausible but for one major flaw. The 16 second time frame is based on an average (mean) time derived from observations of hundreds of tennis players. In psychological methodology the reliance on mean scores in any study is weak and reduces the power of the data. Using mean scores to structure an intervention (mental training) routine ignores a basic and central tenet in psychology, that of individual differences, or in psychophysiology, the concept of "individual response specificity." You cannot accurately base conclusions concerning

individuals on group scores. Each person is unique. Steffi Graf was a less

than 10 second player, whereas Ivan Lendl was a 20 second + player.

Everyone has their own ideal time frame. Although the concept in its pure

form has merit, it is tremendously weakened by stressing a timeframe that

is not cognizant of individual differences. Personality factors and

behavioral tendencies determine one's timeframe. Between point timeframes

in tennis are widely variable and must be ascertained on a case-by-case or

player-by-player basis. Failing to account for

individual differences in between point timeframes would lead to players

acting like robots. Can we really expect players following an "en

masse" prescribed routine to improve significantly? Ask yourself

"how important are between point moments really," or "if

two players follow the 16 second routine to the "T" will there

still be a loser?" The 16

second cure has done little to advance our scientific knowledge of tennis

performance. You will not find a published report on the "16 second

cure" in any scientific sport psychology journal. So go time

yourself. Establish your own between point time frame norm, but donít be

surprised if you donít win the next point even after having followed

your ideal timeframe routine. 3. "A Reduced Pulse or Heart Rate is Associated with Better Performance" or "Slow Your Heart" (Martina Navratilova)Many lay

sport psychologists and analysts, including Martina Navratilova and,

especially, golf commentators maintain (on the basis of what I ask?) that

lowering one's heart rate between points is associated with better

performance. Show me the data!

Crucial is not the baseline heart rate prior to action, rather that a phenomenon called heart rate deceleration kicks in and is accentuated leading up to an action phase of a match (e.g., prior to the return). Heart rate deceleration can take place during high and low levels of baseline ("resting") heart rate. In a study I did, (my Master's thesis in

Psychology) a highly ranked former California junior champion (who will

remain nameless) actually had higher heart rate levels in a match he won

compared to one he lost. However, in the match he won, significantly more

heart rate deceleration between points was evident. Heart rate

deceleration is Again,

here we encounter another trivial statement having little meaning. It

appears commentators and crossover pseudo-psychologists like to hear

themselves spout information sounding scientific even if it is bunk. When you hear these things, please, don't

accept them without investigating their validity. In the case of heart

rate we don't want players and coaches trying to manipulate heart rate in

the wrong direction or confuse physical heart activity parameters with

psychological ones. 4. "Visualization Will Help Everyone Improve" (John Yandell and others)

Although I respect John Yandell's work immensely and recognize his contribution to our understanding of certain components of the imagery process, and in principle recognize that visualization can be a powerful intervention, it is not a cure all, and in fact may be a mental training modality that over 90% of athletes and tennis players cannot even properly access or utilize. My doctoral dissertation research found that only 11% of highly skilled athletes were capable of properly utilizing or engaging in visualization. Again, as in the case of the "16 second cure," it's a matter of individual differences, differences that are not taken into account by most practitioners who teach mental imagery. Mental

Imagery or visualization is the most widely used mental training method

and yet do coaches and sport psychologists really know how effective

imagery is on an athlete-to-athlete basis? Does it really improve

performance? Or, as John Yandell recently astutely recognized,

"visualization may be a continually ongoing process on a subtle and

even unconscious basis," and as my data suggests, not necessarily in

any performance enhancing manner; even after attempts to channel imagery

to improve mental and technical performance. It appears, either you have the ability to utilize and experience and benefit from mental imagery, or you don't, and it appears most athletes don't, at least on a consciously induced or manipulated level. My findings call into question one of the fundamental intervention modalities in sports (mental imagery), suggesting that sport psychologists should assess athletes on certain traits associated with imagery ability first and not routinely administer this form of mental training irrespective of individual differences in the ability to visualize. 5. "There Is an Ideal Tennis Personality or Champions Profile"

|

|||||||||||

|

Vic

Braden and a cohort who calls himself the "Brain Doctor" (a

former Broker without recognized education in neuroscience) claim they are

on the road to finding the ideal championís personality and will have a

DNA brain map of such a person in the near future, disregarding over 40

years of research including my recent dissertation research on over 700

athletes, in one swipe. Their arrogant and false insinuations and

assertions have no merit and will do much to hinder and

"de-motivate" persons not possessing narrow

conceptions of the ideal athlete personality.

As previously mentioned personality factors and behavioral tendencies have

yet to exceed 10% of the variance in the performance equation, with all

types of personalities and personality constellations being represented in

professional tennis at the highest levels. Just contrast John McEnroe with

Stefan Edberg, or Martina Hingis with Venus Williams.

So please, don't buy this myth. Feel free to pursue your tennis goals whether you're a Goran Ivanisevic or Todd Martin type, a Jennifer Capriati or Margaret Court (for you boomers) type. There are much more important and non-psychological factors that will determine how far you get as a tennis player.

6. "Watch Your Body Language"

(Perhaps

the most frequent "Psycho-babble ever babbled on TV)

Whenever

I hear this myth (seemingly everywhere during a sport telecast) I either roll

my eyes or depending on my psychological state yell "I'm sick of

hearing that one again." Body language is an after-the-fact response

to a preceding incident or occurrence during competition. Who creates body

language that counters one's real emotions as sport psychologists want you

to do? Not many players do or can (they try), and it is absolutely wrong

to suggest or for someone to infer that what you see in terms of body

language reflects a "real" emotional state, along the lines of

"what you see is not what you get."

Just because you follow a

coaches or sport psychologists advice to show "positive" or good

body language does not mean your body is going to buy into your fake

positive facial expression or the confident manner in which you hold your

shoulders or stare your opponent into the ground. Moreover, there is

little if any evidence to suggest that body language charades will somehow

lead to better performance or cause your opponent to play worse.

Studies of unconscious processes show that the repression of emotions leads to psychophysiological reactions that may indeed, actually be detrimental to performance. In other words, even though you put on your game face and contain your anger (going into your actorís mode), your underlying unconscious physiological reaction may intensify beyond the level of emotion you were trying to suppress. So the rule here again is, individual differences. Go with your personality and behavioral tendencies. Reactions to tennis occurrences vary as a function of your temperament, they are also temporary and are not likely to affect long-term performance in a match (or even short-term) so long as you do not fight you natural emotional propensities. Let's put an end to this myth.

7. "Don't Think It Just Do It (Nike and others)

Another meaningless psycho-platitude. A saying that says little. Studies actually indicate that top players are constantly engaging in strategic thinking, not only during pre-action phases of a match but during points. The decision to suddenly go for a winner is often preceded by conscious thoughts thereto. Even unconscious processes reflect thinking or active cognitive activity during action or competition. Without a cognitive (or thinking) template you would be helpless on the court. So long as thoughts remain positive and goal oriented you are in good shape. One promising intervention trains athletes to stop negative and facilitate positive thoughts. This individualized intervention (cognitive-behavioral) appears to have more potential than more popular ones such as imagery.

8. You've Got to Get in the "Zone" or Find Your "Ideal Performance State" (Hanin/Loehr)

|

Sounds

good. However, what is the ZONE? What is an "Ideal Performance

State?" The IDS sounds like it came right out of Hanin's Zone of

Optimum Functioning (ZOF) study. Again, here some vague notion of the zone

or ideal state is being "voodooed" upon athletes. Sure, this

state must exist somewhere, perhaps in Hawaii, but will never be found on

the basis of reading some sport psychologist's recipe for achieving it,

especially when being sold to the masses in a cookbook fashion.

The way

to the zone or ideal state is elusive and a long journey requiring

competent practitioners with training in applied psychophysiology and

biofeedback to first establish individual parameters of zone of ideal

state functioning. That means having numerous psychophysiological systems monitored to find out how your body functions when you're playing well.

That is extremely hard to do.

monitored to find out how your body functions when you're playing well.

That is extremely hard to do.

The most promising method is to monitor

heart activity, the only measure you can actually document over the course

of an entire match as I did in my Master's thesis. Once that is done 20

times or so and after having analyzed tons of data, we may actually get a

little bit closer to defining a player's ideal state. But that's just the

beginning. Then a player needs to learn biofeedback under strict monitored

conditions to see if all of those words about having to do this or that to

enter the zone or state actually work. It's a long road.

To date most practitioners just talk about the zone or state but really have never attempted to document it even though there are ways to do so, usually because they lack the training.

In

conclusion, these are some of most transparent myths in Tennis Psychology.

My advice for now, don't believe everything you hear or read. In future

articles we'll dissect the above myths and show how to become your own

sport psychologist by learning more about sport psychological phenomena

and how to critically evaluate it.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think about this article by emailing us

here at TennisONE.

|

Dr. Carlstedt's dissertation on neuropsychological processes in highly skilled athletes (700) from 7 sports including tennis is being nominated for the Society of Neuroscience's Annual 2002 Lindsley Award for Best Dissertation in Behavioral Neuroscience. His Master's thesis was on psychologically mediated heart rate variability during tournament tennis. Future articles for Tennis One will emanate from much of his highly acclaimed and peer-reviewed research. |

Last Updated 6/15/01. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.

In

a study I did a highly ranked former California junior champion

actually had higher heart rate levels in a match he won compared to

one he lost. However, in the match he won significantly more heart

rate deceleration between points was evident.

In

a study I did a highly ranked former California junior champion

actually had higher heart rate levels in a match he won compared to

one he lost. However, in the match he won significantly more heart

rate deceleration between points was evident. associated with heightened attention (concentration) in

anticipation of an important stimulus (e.g. the serve). (More on this and

how to manipulate heart rate deceleration in a coming article.)

associated with heightened attention (concentration) in

anticipation of an important stimulus (e.g. the serve). (More on this and

how to manipulate heart rate deceleration in a coming article.)

TennisONE

is pleased to welcome Dr. Roland A. Carlstedt to our family of

contributors. Roland, a Board Certified Sport Psychologist and

Tennis Coach earned his Doctorate (Ph.D.) in Psychology from

Saybrook Graduate School in San Francisco under the renowned

Personality Psychologist and Behavioral Geneticist Dr. Auke Tellegen

of the University of Minnesota.

TennisONE

is pleased to welcome Dr. Roland A. Carlstedt to our family of

contributors. Roland, a Board Certified Sport Psychologist and

Tennis Coach earned his Doctorate (Ph.D.) in Psychology from

Saybrook Graduate School in San Francisco under the renowned

Personality Psychologist and Behavioral Geneticist Dr. Auke Tellegen

of the University of Minnesota.