<% ns_puts [mkm_getnavbar] %>

Playing John McEnroe:

How To Beat A Big-Time Opponent

By Trey Waltke with Joel Drucker

(Editor’s

Note: - Over the course of his career, TennisONE editor Trey Waltke earned many big

wins. Among his notable achievements was splitting his four matches with John McEnroe – including victories during McEnroe’s prime years in the early

‘80s. Here, Waltke explains the subtleties that accompany playing an opponent as skilled and intimidating as John

McEnroe.)

(Editor’s

Note: - Over the course of his career, TennisONE editor Trey Waltke earned many big

wins. Among his notable achievements was splitting his four matches with John McEnroe – including victories during McEnroe’s prime years in the early

‘80s. Here, Waltke explains the subtleties that accompany playing an opponent as skilled and intimidating as John

McEnroe.)

How do you play a big-time opponent? In 1981, I drew John McEnroe in the

first round of the U.S. National Indoor Championships in Memphis. I had no

delusions: He was better than me, which meant it was critical to think

about the right game plan if I wanted to play the best possible match.

And here's the lesson, no matter what your playing

level: Preparing for a match isn't a matter of blindly thinking about how

you're going to hit 60 winners. Planning to win requires thoughtful

analysis of how your game appropriately matches your opponent's.

Here's what I thought about me versus McEnroe:

He's got a finite amount of weapons -- albeit in McEnroe's case, a pretty

broad selection. But he's only human and, like all players, McEnroe

has lost before and has his share of weaknesses. So my challenge was to

hone in on finding those weaknesses and exploiting them as much as my

particular style would permit. Maybe this realism comes from having grown

up in Missouri, an austere place also known as the "Show-Me"

state.

Now don’t misunderstand me. Playing a McEnroe-level player makes you hyper-alert. That awareness is mixed with the fear that if you don’t impose your game on him promptly, you’ll conceivably lose quickly and embarrass yourself in front of a lot of people.

|

It’s vital never to show how worried you might be. Players like McEnroe are sharks. The minute he smells any fear, he’s all over you. But if you don’t reveal a single emotion, you can get your opponent a bit off-balance. After all, he’s not a mind reader and for all you know, he might be a bit scared of your own tools. Experience has taught me that you can never tell how two players will match up until they actually play one another. Everything from pace and spin to movement, shot selection and the competitive aura each player exudes on the court figures into this.

The first time I saw McEnroe play he was still a junior. His game looked flimsy, too dependent on his superb hands and less reliant on hardcore fundamentals. This was particularly true with his groundstrokes, especially his forehand. Even his backhand didn’t seem that strong, mostly a short stroke he pushed around the court.

Then, the next summer, John McEnroe went right from his high school graduation to the Wimbledon semis, instantly creating the aura of a champion. On the one hand, we on the circuit were shocked by his utter lack of respect for anyone on the tour. At the same time, we were awed by his skill at pulling it off. In the fall of ’77, I played him in doubles. Word had it he was even better in doubles than singles, so now, playing at the Los Angeles Tennis Club, I had the chance to experience it first-hand.

McEnroe was a doubles genius. He was hitting shots I’d never seen from a pro -- curving low lobs, wickedly early angled service returns, midcourt swinging volleys. He’d stand practically in the middle of the court, daring me to out guess him on my return of serve. It was precisely the kind of brilliant movement and ballstriking that could instantly take you way out of your game.

|

But again, even versus a genius like McEnroe, you must look beyond the

artistry to the craftsmanship. Even the brilliant McEnroe had preferred

patterns. For example, he had a great serve to the backhand in the ad

court. My response: put my left foot in the alley when receiving so as to

make him feel he had a smaller space to serve into. I wanted him to know

that I was ready to play a backhand return - my strong side. And at the

same time, I was daring him to hit the serve down the center - a shot

that's more difficult for lefties. Granted, McEnroe hit the center serve

as well as anyone, but at least by stepping into the alley I was letting

him know that it wasn't going to be so easy for him to play that classic

lefty combo of the swinging wide serve and the angled backhand volley.

Making a guy play shots or sequences he'd rather not play is a great way

to at least attempt to establish a toehold.

Another thing I noticed was that McEnroe’s first volley was phenomenal if you hit the return with pace. On the other hand, if you were able to get his serve back with a low, off-pace return, his tendency was to float the half-volley back to you and then, almost as a bluff, he’d close in on the net. Standing in like this off a weak shot left McEnroe vulnerable to quick lobs over his backhand shoulder. So again, I knew I’d need to take a lot of pace off my return and just get it down low at his feet. Not easy, but actually, for me, that soft, slice backhand was one of my favorite shots.

Serving to McEnroe also offered a few possibilities. He didn’t crack his backhand very offensively if you got your first serve in. This made me concentrate very hard on getting first serves in because he loved attacking second serves. Likewise, his groundstrokes didn’t always penetrate, so you had to keep hitting your own deep in order to elicit a short ball and force him to pass you.

You also had to account for the fact that at some point during the match, especially if the match wasn’t going his way, he was going to stop your momentum by throwing a tantrum, yelling at an umpire or even retying his shoes just before a critical point.

|

There was also an emotional aspect. The winner of our match was supposed to play a local teenager named Jimmy Brown. Everyone figured it would be McEnroe and Brown in the next round. I didn’t like that at all. Would you? Once you’ve done the rational stuff, there’s something to be gained from letting anger motivate you too.

Granted, the tiny holes in McEnroe's game weren't

always there, but at least my homework gave me a few rungs to hang my hat

on. But it's sure better to try and win with a couple of basic tactics

than delude yourself into thinking you're going to suddenly hit dozens of

winners.

This brings up a point I've been trying to teach juniors: Winning tennis is usually boring tennis. To beat someone of equal or greater ability, you must be willing to do whatever it takes over and over again. Too many juniors get caught up thinking they have to beat someone with big winners. The object is to find that small chink and patiently drill at it at like a dentist slowly filling a cavity. And everyone's got some teeth that are weaker than others -- even John McEnroe.

Winning tennis is usually boring tennis. To beat someone of equal or greater ability, you must be willing to do whatever it takes over and over again.

That night in Memphis, I won 6-3, 6-4. From the time he walked on the court, I sensed McEnroe was preoccupied, not quite paying attention to how he was going to actually win rather than let his aura do it for him. So this gave the shark in me a little blood. As anticipated, he began stalling – a sure sign I’d at least made a dent (McEnroe never stalled when he was winning handily). After the first set, I knew the second set would have even longer periods of stalling, so I made sure to keep myself focused and never get bogged down in John’s negative energy.

|

|

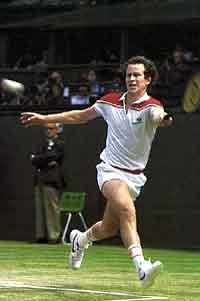

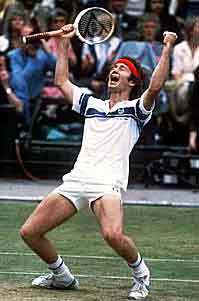

Vintage Mac - he had few weaknesses on grass. At Wimbledon, he was nearly unbeatable. |

|

Our next match came two years later, in Las Vegas. I applied the same strategies, and was able to scrape out another victory. Now again, I’m not going to say I was a better tennis player than John McEnroe. It was just a matter of styles and moments. We played our final match later that summer in the first round of the U.S. Open. I took a two sets to one lead.

McEnroe was livid. This wasn’t just another Memphis or Vegas. This was the U.S. Open. The stadium was teeming with that buzz: a top player was in trouble. When you’re younger, these opportunities for big wins are tricky. A few years before, playing a tight match against Adriano Panatta at the Italian Open, I was oddly afraid to grab the big win. But now, against McEnroe, I knew that I’d beaten him before, and I wasn’t scared to beat him. He knew this too.

So early in the fourth set, on a changeover, he got about one inch from my face and spewed out several choice obscenities. I’d planned for him stalling, but even this I hadn’t planned for. Along with Pancho Gonzales and Jimmy Connors, McEnroe was that rare player who could get better when he got angry. It got me a bit off-balance.

|

But more importantly, McEnroe validated the lesson of this story: you must understand your game and understand what makes you win. For all the talk about McEnroe’s creativity and touch, to me his real genius was his ability to play aggressive percentage tennis. When they’re in trouble, great players don’t just start flailing. They’ll attack, but they’ll do so in a very buttoned-up way. Playing within yourself means never going for more than you need to. McEnroe was a master at this.

As the fourth set got underway, John began paying more attention to covering the court – and in short order, he began swarming me with lots of first serves, solid volleys and consistent returning. Those little mistakes that had cost him earlier in the match vanished. The last two sets went to McEnroe, 6-0, 6-1. I’d tried hard, but in many ways, he was just a quicker, more talented version of me – too tough.

Still, whether in victory or defeat, the lessons I learned playing McEnroe apply to anyone: Don’t get overwhelmed by your opponent’s aura of greatness. Assess his game logically. Study patterns. Find ways to make your opponent play shots they don’t like, hopefully by hitting the shots you like hitting. Run the same boring play, again and again – because there’s nothing boring about a victory. And the next time you hear someone say, “I just didn’t play my game,” make a mental note to congratulate their opponent for not letting them.

Your comments are welcome. Let us know what you think by emailing us here at TennisONE.

Last Updated 5/1/01. To contact us, please email to: webmaster@tennisone.com

TennisONE is a registered trademark of TennisONE and SportsWeb ONE; Copyright 1995. All rights reserved.